A physician-virology researcher shares her perspective on the possible connection between common herpes viruses and Alzheimer's disease - and what it means for our health.

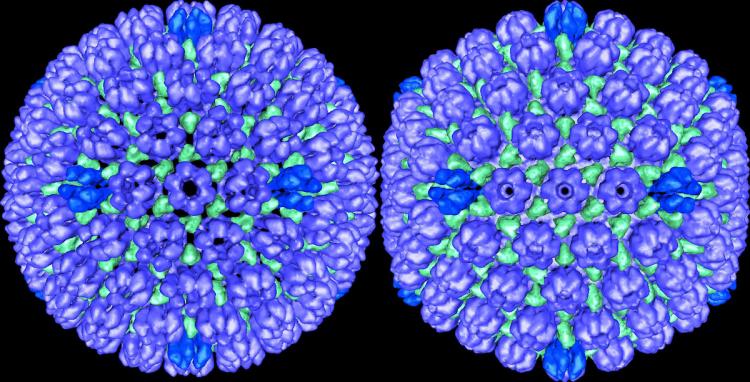

New research out of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is making a splash in the media. In a study published in Neuron using tissue from four brain banks and an NIH-funded genetic database, the researchers found that the brains of people with clinical and pre-clinical Alzheimer's disease had more herpes viruses than the brains of unaffected controls. They also showed that the viral genes influence the activity of human genes associated with Alzheimer’s risk, providing evidence that common herpes viruses, especially herpes viruses 6A, 7, and herpes simplex virus 1, play a role in triggering disease mechanisms.

In light of these findings, we spoke with Dr. Christine Johnston, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Medicine and associate director of the UW Medicine Virology Clinic. She has studied genital herpes for 10 years and is now building a collaboration with the UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center to investigate the link between herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV 1) and Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Christine Johnston, MD, MPH

Why did you first become interested in the herpes virus-Alzheimer’s link?

In the world of genital herpes, we’ve learned that HSV 1 and 2 cause a chronic low-grade infection and can cause inflammation in the genital tract. There have been a lot of studies over the years showing a link between HSV 1 infection and Alzheimer’s disease. HSV 1 is a neurotrophic virus, meaning it likes to infect the central nervous system, and when it causes severe disease such as encephalitis, the virus affects similar regions of the brain as does Alzheimer’s.

For me, it is the laboratory studies of HSV 1 in cell cultures and mice models that convinced me of the need to study the Alzheimer’s link further. These studies show that HSV 1 can induce the formation of beta amyloid and tau proteins, providing evidence of a biologically plausible mechanism for how these viruses could play a role in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Or, it could be that the virus is always there at a low level and is continually triggering this immune response. There has also been increasing evidence that inflammation is contributing to Alzheimer’s disease. Based on this developing understanding, and my knowledge of what happens in genital tract, I became very interested in exploring the link between HSV 1 and Alzheimer’s disease in more detail.

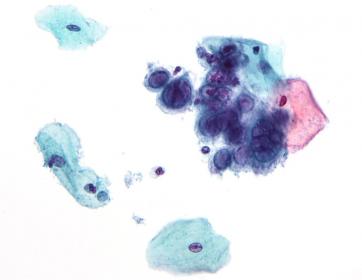

Artistic rendering of the changes of the herpes simplex virus in human cells. Credit: Nephron, Wikipedia

As people are probably wondering, what do these findings mean for public health and risk of Alzheimer’s disease?

The bottom line is that herpes infections are extremely common. HHV-6 and HHV-7 are acquired by nearly everyone in childhood, and the body cannot clear them. These viruses typically lie dormant for years. Similarly, HSV-1 affects about 60% of the US population. I don’t think people need to be overly concerned about having these viral infections that all of us have, or how that’s going to contribute to Alzheimer's risk. At this stage, I think that the link between the herpes virus family and Alzheimer’s disease is an interesting scientific finding, but we still need to better understand how these viruses could affect Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and clinical trajectory.

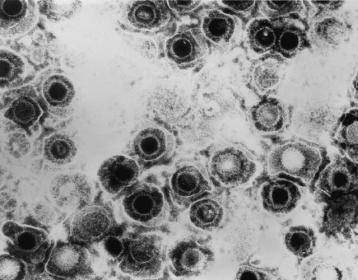

Transmission electron micrograph of herpes simplex virus. Credit: CDC/Dr. Erskine Palmer

Might some people be more susceptible than others to a develop Alzheimer's disease triggered by a herpes infection?

I do want to be clear that I don’t think that any herpes viruses are the cause of Alzheimer’s disease; rather, multiple factors interact. One of those is the common genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's, ApoE4. There’s evidence that people with the ApoE4 genotype are more likely to develop HSV 1 oral lesions, and so there may be some interaction between ApoE4 and herpes viruses that creates the perfect storm.

Aging is definitely also involved. We see increased activation of herpes viruses with age, and immunosuppression in general, such as after bone marrow transplants. So, we speculate that something about the immune system changes as we age, which contributes to decreased control of herpes viruses.

Do you think this research opens an avenue for a herpes virus antiviral medication or vaccine to prevent Alzheimer's disease?

Yes, I think antivirals or vaccines could be a hopeful direction for prevention or treatment in the future, but a lot of work needs to be done. As these infections are chronic, low-grade processes that happen over years, we first need to know at which point do we need to treat an infection to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Would we need to treat it at very early stages before symptoms onset, and therefore need to identify people at risk? Could treatment be effective in later stages of Alzheimer’s disease, or is the damage already permanent?

We do have effective antiviral medications for some herpes viruses, but the potential long-term toxicity would need to be evaluated. A vaccine for herpes viruses has been elusive thus far. For HSV-1 and HSV-2 and cytomegalovirus, we haven’t been able to develop an effective vaccine despite extensive work. So potentially, a vaccine could be helpful, but we have a long way to go.

Will we eventually be calling Alzheimer’s disease an autoimmune disease?

I wouldn’t call Alzheimer’s an autoimmune disease. I think we could potentially say that chronic viral infections contribute to Alzheimer’s, but it’s such a complicated disease that I don’t think we will ever think about it as one type of disease. We know there are genetic and environmental risk factors, and perhaps this work will reveal viral risk factors as well.

What questions are you pursuing in your developing collaboration with the UW Alzheimer's Disease Research Center?

We have a grant submitted to focus on questions about HSV 1 and Alzheimer's disease, using epidemiological data: Are people who are HSV 1 infected at an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s neuropathology and symptoms, or an accelerated course of Alzheimer’s? We are also looking at whether viral shedding in the mouth (a proxy for how active the virus is in a person) is associated with an increased progression of Alzheimer's disease. And in a separate proposed ADRC collaboration, we will determine the relationship between HSV-1 infection and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in a mouse model.

From the herpes virus side, we feel like we are in a prime location because we can leverage the ADRC's incredible resources, including the clinical cohort of participants, the repository of brain specimens in the ADRC Neuropathology Core, and researchers who can ask the right questions.