Lumbar punctures, cerebrospinal fluid, and biomarkers—these are three terms that form the horizon of our center’s research. Biomarkers are biological indicators that may lead us to a prevention or cure for Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrospinal fluid is the substance in which some of these biomarkers are found, and a lumbar puncture is the method used to access cerebrospinal fluid.

Often, when we tell people that lumbar punctures are a common part of our research, we are met with a bit of reservation. That reservation is understandable, but we hope that by providing clear information about the procedures and answering some common questions about the procedures, we can help make lumbar punctures seem less invasive and risky.

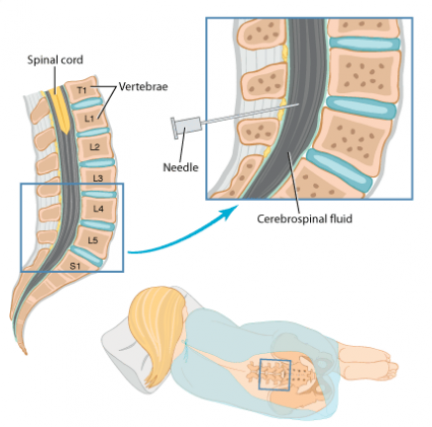

The needle location of the lumbar puncture. A lumbar puncture video can be accessed on YouTube.

What is a lumbar puncture?

A lumbar puncture (also called a spinal tap or an LP) is a common medical procedure in which doctors remove a small sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from a person’s lower back (“lumbar” region). During an LP, participants lie on their side, which allows doctors to easily access the area of the lower back where the LP will occur. Once participants are in position, doctors use a local anesthetic to numb the area and then use a thin needle to draw out a small amount of spinal fluid. Because the anesthetic numbs the area, the LP should not be particularly uncomfortable or painful. After an LP, participants occasionally feel mildly sore as a result of staying in an unfamiliar position during the procedure. If participants are sore after an LP, they can take a standard pain reliever like Tylenol.

Are lumbar punctures safe?

Yes. Our center has improved the procedures for research lumbar punctures and has created safety guidelines that are followed throughout the field. To read more about the safety and acceptability of lumbar punctures, please click here.

Will I have a spinal headache after the LP?

We have performed over 2,000 LPs at the UW ADRC and have improved the procedure to reduce discomfort and to minimize the chance of LP-related headaches (known as spinal headaches). In fact, less than one percent of our participants experience significant spinal headaches. However, when they do occur, these headaches can be quite painful. If someone gets a mild headache following an LP, we treat it with Tylenol and beverages that are high in caffeine. In the rare case of a severe headache, we perform a simple medical procedure called an epidural blood patch to relieve the pain. Most spinal headaches can be avoided by following the instructions and follow-up care provided by our physicians.

What is CSF and why is it so important?

CSF is a clear, colorless liquid that is in direct contact with the brain. It provides a cushion to the brain and spinal cord and may serve some purpose in the chemistry of the brain (which is not clear to us at this point). Importantly, since the CSF interacts very closely with the brain, many researchers believe that it can provide a more direct window into changes that may be occurring there. CSF contains a variety of proteins that researchers measure and analyze. The goal of this analysis is to identify markers (biomarkers) for Alzheimer’s disease that will improve with accurate diagnosis, "preclinical" diagnosis in persons with no memory symptoms who are destined to have Alzheimer's in the future, and monitoring response to therapies. This type of monitoring will be particularly important as we try to develop new treatments.

What happens to my CSF after it is collected?

At the ADRC, CSF samples are kept within a collection called the ADRC Research Repository. This repository has the largest collection of CSF samples from individuals with no memory complaints (control participants) in the world, and is utilized by a large research community. These samples are particularly important as a group because the collection can be studied for specific research questions related to Alzheimer’s disease.

The Lumbar Puncture Myth Buster

As published in Dimensions

Dr. Elaine Peskind, UW Professor of Psychiatry and former director of the UW ADRC Clinical Core, reinvented the way research lumbar punctures, or spinal taps, are done, making them safer and less painful for research participants. But urban legends and myths of pain, meningitis, and paralysis are still associated with the procedure. Dr. Peskind, who has performed more than a thousand lumbar punctures during her work at the ADRC, takes a look at a handful of these fables and reveals the truth about research lumbar punctures.

MYTH: Lumbar punctures are really painful.

The discomfort associated with a lumbar puncture seems to vary from person to person. Most people report that the only painful or uncomfortable part of the procedure is a very brief sting they experience when the local anesthetic or numbing medicine is injected. This local anesthetic is similar to the one you would receive at the dentist, and it is used to prevent pain during the lumbar puncture. As the needle for the lumbar puncture is positioned to collect spinal fluid, most people describe the feeling as a pressure sensation. In a study we did at the ADRC, we found that, overall, anxiety and pain ratings were low among the research participants who had lumbar punctures. Most people are surprised at how comfortable the procedure is, and occasionally a person will sleep through the procedure.

MYTH: There is a chance that a person could get meningitis by participating in have a lumbar puncture.

People cannot develop meningitis from a lumbar puncture that is conducted properly. The worry over meningitis and lumbar punctures perhaps arose because bacterial meningitis, which is a condition where bacteria makes its way into the spinal canal, is diagnosed by using a lumbar puncture to collect spinal fluid for testing.

MYTH: If a person gets a lumbar puncture, that person will have a bad headache afterwards.

When doctors perform a lumbar puncture, they puncture a fluid-filled sac that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Spinal headaches occur when the spinal fluid continues to leak (under the skin) from this puncture. A true spinal headache worsens when a person is sitting or standing and improves when that person lies down. After a lumbar puncture that is conducted for medically necessary reasons, 10 to 30 percent of people develop a spinal headache. However, for research lumbar punctures at the ADRC, we use techniques that make the headache rate much lower—less than 1 percent of our subjects report having spinal headaches. This difference is mainly caused by the gauge (thickness) of the lumbar puncture needle and the shape of the needle tip. In the ADRC research lumbar punctures, the needle inserted into the sac has a smaller gauge and duller tip than the needles that are commonly used during medically necessary lumbar punctures. This difference means that in a research lumbar puncture at the ADRC, the tip of the research needle slides between the fibers of the sac that contains the spinal fluid rather than cutting through it. Because those fibers are not cut and because the hole left by the needle is smaller, the puncture site seals quickly and prevents the spinal fluid from leaking out.

MYTH: If the doctor sneezes while someone is undergoing the procedure, that person will become paralyzed.

The spinal cord ends about five inches above the spot where the lumbar puncture needle is inserted. Because the needle is inserted well below where the spinal cord ends, there is almost no chance of nerve damage or paralysis. Nerves branch off the spinal cord and dangle loosely down through the lower part of the spine. Sometimes the needle may brush against one of these nerves, which may cause a brief “electric” twinge to go down the person’s leg but results in no other symptoms, particularly not paralysis. This feeling usually goes away quickly, but if the twinge returns while spinal fluid is being withdrawn, our doctors will quickly readjust the needle, which usually stops this brief discomfort.