As published in Dimensions Magazine, Spring 2018

By Justina Bagger, UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

Every day, I venture up fourteen floors in the Ninth and Jefferson Building in Harborview Medical Center to start another day as a Research Coordinator at the UW Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). My job involves helping to run the ADRC’s longitudinal clinical research study. I do things such as schedule participant visits, process blood samples, and administer memory and thinking tests, also called neuropsychological testing, or just cognitive tests.

To me, cognitive testing is more than just scores. The purpose of cognitive testing is to detect the onset and worsening of cognitive decline or, hopefully soon, the improvement after an intervention. It’s also an important step in my career goal to become a clinical neuropsychologist and conduct research of my own.

Cognitive Testing at the ADRC

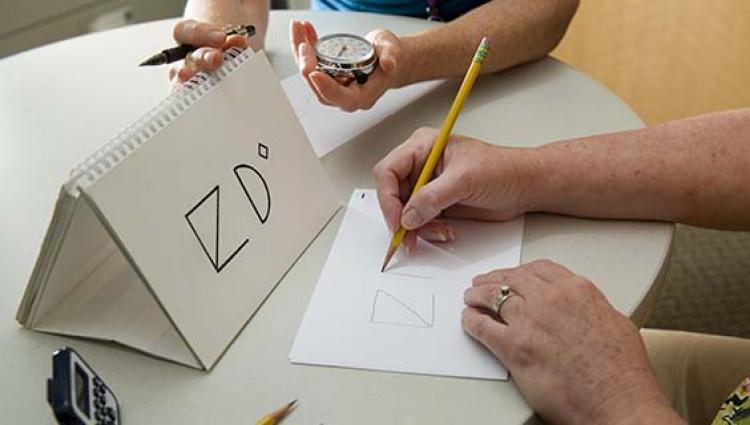

On a research participant’s first visit, we establish his or her baseline starting point of memory and thinking skills by giving him or her a series of tests. These exercises may involve copying drawings, naming pictures, reciting a brief story they heard five minutes ago, or repeating back a sequence of numbers and letters. These varied tests capture a snapshot of the person’s long and short-term memory and many other domains of thinking such as attention and language.

This study, run by the ADRC clinical core, is called “longitudinal” because every year after the baseline tests are done, the people come back and do the same cognitive tests. This is how we detect significant changes in cognition over a person’s life.

Taking into account our individual differences is crucial for interpreting the results of thinking and memory tests. Each person’s own strengths and weaknesses are a key factor in how neuropsychological testing is interpreted. For example, if someone was always bad at managing money, then poor performance on the finance test questions might not reveal a problem, but it would signal a troubling change for someone who used to be a banker.

But how does our team learn about the detailed life history that a research study demands? After all, a participant might not report everything we think is relevant. We need to have a co-participant (a family member or close companion) who can tell us about the participant’s history and how they think that participant is currently doing.

Co-Participants

NIH

Co-participants are a critical part of interpreting neuropsychological testing over time, as they give more detailed background and paint a bigger picture than just scores from tests. Every research participant in the ADRC longitudinal study has a co-participant; it is so important that we actually require a co-participant to be co-enrolled!

I got my first exposure to cognitive tests and the role of co-participants during a summer fellowship at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. I was involved in work on potential health or lifestyle predictors of Alzheimer’s disease (such as sex, age, pre-existing neurological diseases, or traumatic brain injuries) using a database of several hundred Alzheimer’s disease research participants. Each participant had a diagnosis of memory decline or dementia and a co-participant(s) from his or her family.

In our statistical analysis of the data from co-participants, we found a pattern in how different generations of a family perceived changes in a loved one’s memory function. In other words, we found that spouses or siblings generally reported more memory loss than did grandchildren.

This finding led to bigger questions for me. “Why?” was my main question, and at the 2017 International Neuropsychological Society Conference, I presented my ideas in a poster session. One theory is that a grandchild could be expecting a grandparent to have memory decline. Another theory is that grandchildren might not have known the grandparent in decades past when they did not have any cognitive problems, leading them to have a skewed sense of what is normal thinking for their grandparent.

While both of these ideas seem logical to me, they are just starting points for my research plan to investigate co-participant reports further. Co-participant reports sometimes are viewed as less than ideal because they are very subjective: there are many variables that can influence how co-participants gauge the mental status of the participant, which might reflect the co-participant’s experience instead of the participant’s abilities. For example, something as seemingly simple as a co-participant’s mood, or even normal lapses in the co-participant’s recall, could potentially skew their report.

To me, this is an opportunity to make this abundant resource more reliable. As part of my long-term research goals, one project I want to tackle would be creating mathematical adjustments to apply to the co-participant reports. The end goal would be to take into account different factors that affect co-participant reports, such as generational differences, to capture the truest state of the participant. This is important because when we are able to accurately determine the state of the participant—even his or her communication and short-term memory change over time—we can improve the effectiveness of research and care.

A Debt of Gratitude

Justina Bagger, Research Coordinator

To me, all the co-participant reports are a gold mine of potential information for our center, and for my long-term project. This project will take time and plenty of more data points. So, to all of the co-participants who are involved in our studies at the UW ADRC, thank you for your past and future reports about your loved ones. The ADRC clinical team members, who all conduct co-participant interviews, appreciates your selfless contributions to our research and find them to be an especially meaningful part of the job. With your support, the ADRC will continue to move research forward to discovering treatments and providing the best care possible.

- Meet the ADRC Research Staff