.png)

by Ari Bleu Conboy

The city of Longview is proud of much of its history. Located on the Columbia River and southern border of Washington state in Cowlitz County, it is easily reached from the I-5 freeway that connects Seattle and Portland. Travelers drive past a large green sign warmly welcoming them to “R.A. Long’s planned city”. R.A. Long, the head of the Long-Bell Lumber Company, optioned 70,000 acres of prime timberland in 1920 and within a few years was operating the largest sawmill complex in Washington state. He also established one of the country’s first “planned cities”: a town that was entirely planned, zoned, and designed for future growth before construction began in 1922. He named it after himself and planned for a population of 50,000 which would have made it one of the largest cities in the state at that time. Although the population dream would never be realized (today the city houses 38,000 residents) and the company would be sold in the 1950s, the story of R.A. Long and his planned city continues to make residents proud.

Yet, some aspects of the city and county history are less well known. This essay explores the history of racial exclusion, including the use of racial restrictive covenants to prevent persons of color from owning, renting, or occupying housing. These were among the tools used by the Long-Bell company and county and city authorities to insure that the county remained all white. As late as 1970, people of color comprised only 1.1% of the county population and that included the remaining members of Cowlitz tribe. Longview was indeed a “planned city.” As our research demonstrates, it was planned as a “whites only” city.

Early history

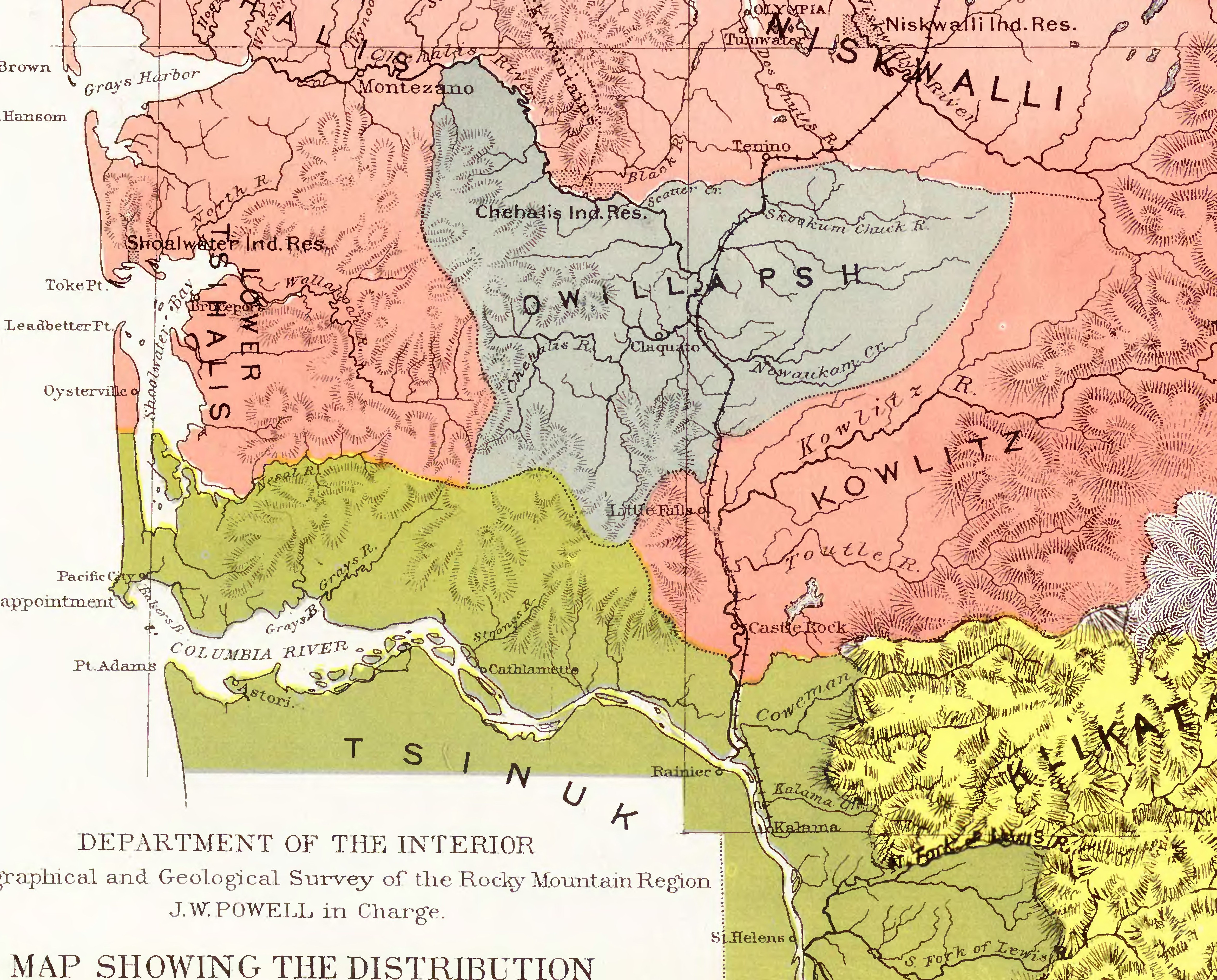

The practice of racial exclusion predated R.A. Long. The Cowlitz Tribe has a long and rich history passed down through the generations. The word “Cowlitz” directly translates to “the people who seek their medicine spirit”.[1] In addition to being deeply spiritual, the Cowlitz people had well established tribal dynamics and divisions. The Cowlitz had four different “tribal bands”, or groups that differed based on location, language, and practices. These bands included the Lewis River Cowlitz Band, the Lower River Cowlitz Band, the Kwalhiokwa Cowlitz Band, and finally the Upper Cowlitz Band. While these groups did inhabit different territories, there were no harsh lines drawn between them and they frequently overlapped and interacted with each other. Unlike their future white colonizers, they did not claim to own the land. Instead, it belonged to the earth.[2]

After the United States claimed the territory in 1846, the Cowlitz were forced to surrender their land and were never acknowledged by the US government or allowed to reserve tribal territory.[3] On the other hand, white settlers were entitled under the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 to claim 320 acres of formerly tribal land as their own while the Cowlitz people were forced off their ancestral lands with no safe means to protest.[4] This was the beginning of racial exclusion and division in Cowlitz County.

White Americans moved slowly into Cowlitz County, mostly seeking farmland near the Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers. The Northern Pacific Railroad pushed through the county in the 1880s, bringing more settlers. The federal government supported the railroad by turning over thousands of acres of timberlands, much of which the railroad later sold to Weyerhaeuser timber company. But farming provided the livelihood for most of the county population, numbering less than 12,000 in 1920. That was the year when R.A. Long bought most of the Weyerhaeuser tract.

Bust of R.A. Long erected in 1942, eight years after his death (photo: Kearby Chess, Wikipedia).

Bust of R.A. Long erected in 1942, eight years after his death (photo: Kearby Chess, Wikipedia).

Robert Alexander Long was born in 1850 in Shelbyville, Kentucky where his parents were the proprietors of a large and profitable farm. After a failed business venture in the early 1870’s, Long changed course and moved to Columbus, Kansas. There, in 1875, he and his business partners, Victor Bell and Robert White, started the R.A. Long and Company, which would soon be named the Long-Bell Company. In the following decades, Long-Bell owned and operated timberland, mills, retail years, and company towns across the country in Kansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Arkansas, Michigan, and Wisconsin.[5] However, by 1918, R.A. Long was faced with the age-old dilemma of harvesting finite resources: his southern mills were running out of trees to cut down.[6] The answer that Long and his board of directors came up with was simple: move operations westward where there is an “infinite” supply of high quality lumber.[7] At this point, forest conservation was the last thing on their minds. Their primary concern was continued financial growth.

Long and his fellow executives visited the old-growth forests of Cowlitz and Lewis County, then owned by the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, and soon purchased a whopping 70,000 acres of timber. Wesley Vandercook, the chief engineer of the Long-Bell Company, tackled the enormous task of surveying the area and producing a plan for a large-scale mill, selecting and purchasing 13,000 acres of the land near the confluence of the Cowlitz and Columbia rivers as the site for the mill and its expected work force.[8]

Company planners understood that the timber industry in Washington faced different workforce issues than in the South. At southern Long-Bell mills, workers were readily available and the company tried to avoid unions by exploiting racial divisions, often hiring both black and white workers though black workers were paid considerably less and constantly faced workplace harassment. Mexican workers were also employed at Long-Bell mills and faced similar levels of harassment.

The situation at the future Longview mill would be quite different from the southern Long-Bell mills. Skilled sawmill workers would need to be recruited to the area and the company was worried about Wobblies, members of the Industrial Workers of the World. The IWW had been very active in the timber camps and mill towns of Washington state, staging a wave of spectacular strikes in 1917 and now in 1920 was active again.[9]

Mr. Long knew that his proposed mill, which would become the largest in the world at the time of its construction, required a high quality workforce to match it. He also knew that existing logging operations were unwelcoming to men with families, who he viewed as a reliable and untapped resource. With all these factors in mind, Long intended to build a company town and mill of unmatched scale. The planned town would attract families and allow the company to keep out IWW members and other potential threats. It would also keep out nearly everyone who was not white. The town that would eventually be named Longview, after R.A. Long’s enormous horse farm in Missouri, was planned to accommodate a population of 50,000 before construction even started.[10]

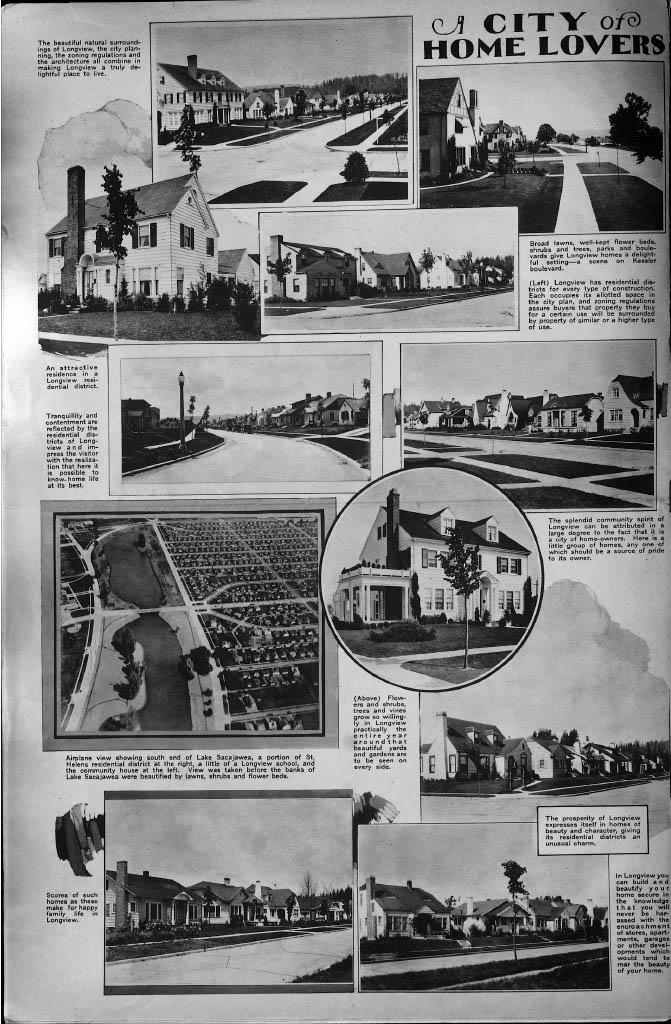

Long envisioned a budding city with beautiful public parks, public transportation, family friendly residential communities, and an international port that would support his lumber empire. To make this vision a reality, Long worked closely with the well known city planner, and fellow southerner, J.C. Nichols, who designed a similar residential community in Kansas City. The two men were going to build the “model city”, one that was intentionally zoned to regulate what kind of developments were built and where, whether it be residential, commercial, or industrial.[11] One critical feature the southerners agreed upon would forever shape the character of Longview: racial restrictive covenants would be written into a majority of the property deeds in the town. With everything in place to build a haven for white families, construction began in the summer of 1922.

Uniquely Restrictive

Racial restrictive covenants were a mode of racial segregation available to private property owners who wanted to regulate which groups of people would be allowed to buy, lease, or rent their property in perpetuity. These covenants were legally enforceable clauses written into property deeds or records. Segregation in Washington differed from the well known southern style of segregation, which required racial separation in all public, and most private, facilities. Outside the south, however, white property owners relied upon racist covenants to keep their neighborhoods white and property values high. It is important to note that racial restrictive covenants were distinct from redlining. Redlining originated from the period following the Great Depression when the federal government created the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Authority, which were intended to turn America into a “homeowners nation” by subsidizing new mortgages backed by government insurance. The Homeowners’ Loan Corporation then created the infamous redlining maps which denoted communities of color as “hazardous” to mortgage lenders by coloring them red on the maps.

Since the entirety of Longview and the surrounding wooded areas were privately purchased by the Long-Bell Company and R.A. Long, they were legally able to restrict any property they wished and did so at an unprecedented scale. Cowlitz County has the highest percentage of restricted properties in all of Washington State with over 8,000 restricted properties currently identified

Our maps show the extent of the restrictions. Nearly all residential properties in Longview and West Longview are covered by racial restrictions, which have been void under federal law since 1968. The neighborhood east of downtown was intentionally left unrestricted. Located near the river and industrial plants, this area was intended for modest dwellings and would allow residents of color.[12] According to the Longview Daily News, this area–Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Avenues–was commonly referred to as the “negro section” or “colored town”.[13] Even so, very few Black or Asian people settled in Longview or Cowlitz County. The 1940 census counted only 241 nonwhite persons in the entire county (population 40,155), 75 of one of them Black.

Victoria Freeman was one of the 75. A local trailblazer, Freeman was the driving force in integrating the Longview Public School District when she tried to enroll her two sons at the Kessler School in 1924.[14] She, along with the other few residents of color, were forced to live in the underdeveloped eastern industrial section of the town, the so-called “colored town”. In 1961, Victoria Freeman’s granddaughter, Cynthia Washington-Mattson, attended Mark Morris High School, a local Longview public school.[15] One day, as she entered a required school assembly she was horrified to see multiple of her classmates in blackface. Those that chose to walk out in protest of the racist display were the only students suspended. Two years after the 1961 incident, a group of black children decided to walk outside of their designated area, or past Eighth Avenue, and were immediately shot with BB bullets which were fired by another child. Once they retreated back to Eighth Avenue, their mothers called the police to report the incident. No officer ever came.[16]

Today, one can find Victoria Freeman Park, which was renamed after death in 1994, in the same area of Longview where she lived. On the multiple plaques that describe Freeman’s legacy around the town, Longview is ironically framed as an early racial integration haven. While schools were integrated far before it was federally mandated, these plaques skillfully leave out any mention of racial restrictive covenants which were recorded up until the early 1950’s.

8th grade class photo from Kessler school in 1950 shows that the city's so-called integrated school system was predicated on the fact that there were only a handful of nonwhite students living in the city. (Courtesy: Longview Public Library)

8th grade class photo from Kessler school in 1950 shows that the city's so-called integrated school system was predicated on the fact that there were only a handful of nonwhite students living in the city. (Courtesy: Longview Public Library)

And here is the point: school integration was the only option for a city with such tiny numbers of Black, Asian, and Indigenous children. Otherwise, Longview would have had to build a separate school system.

By keeping homes of different values–and people of different races–separate, city planners were able to assure white residents that they did not have to worry about fluctuations in their property values. These intentions were stated in magazines and pamphlets designed to attract new residents and workers. One advertisement reads:

"It [Longview] is a healthful city offering a clean, wholesome environment for the rearing of children. Its residential districts are well planned, served with modern public utilities and protected by zoning and building regulations designed to safeguard property ownership and stabilize property values."[17]

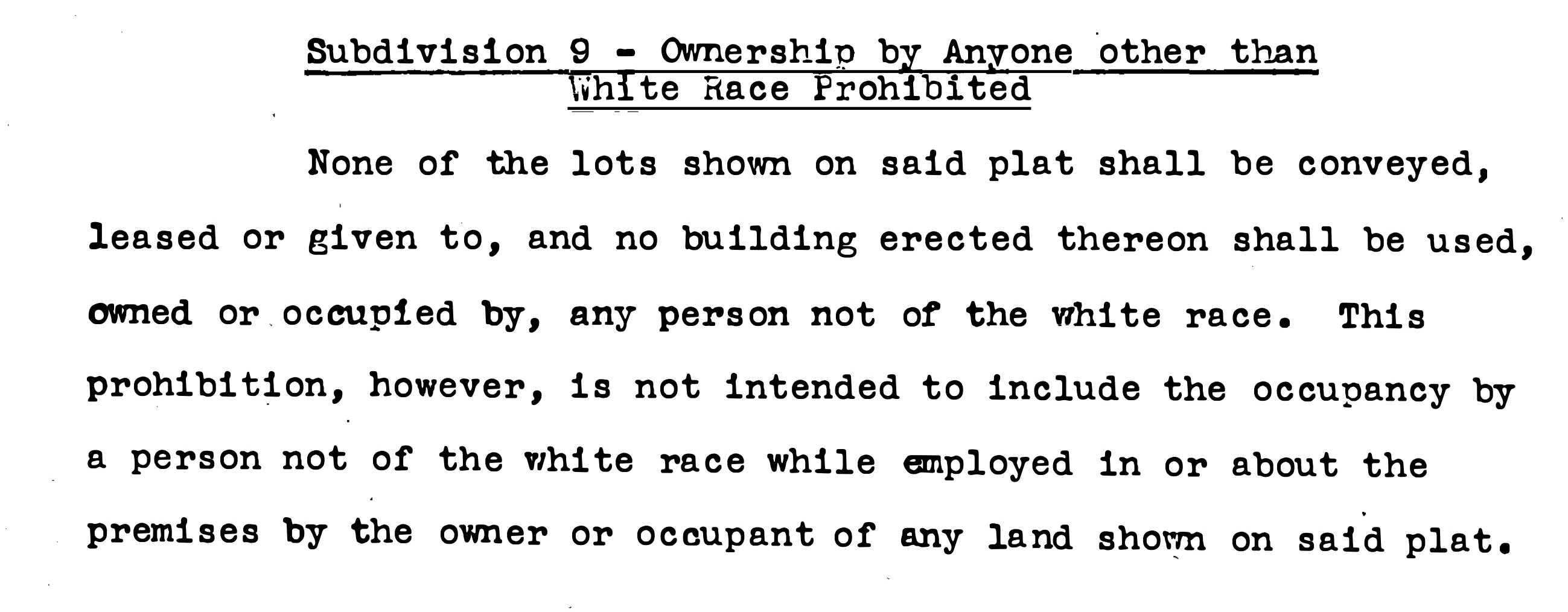

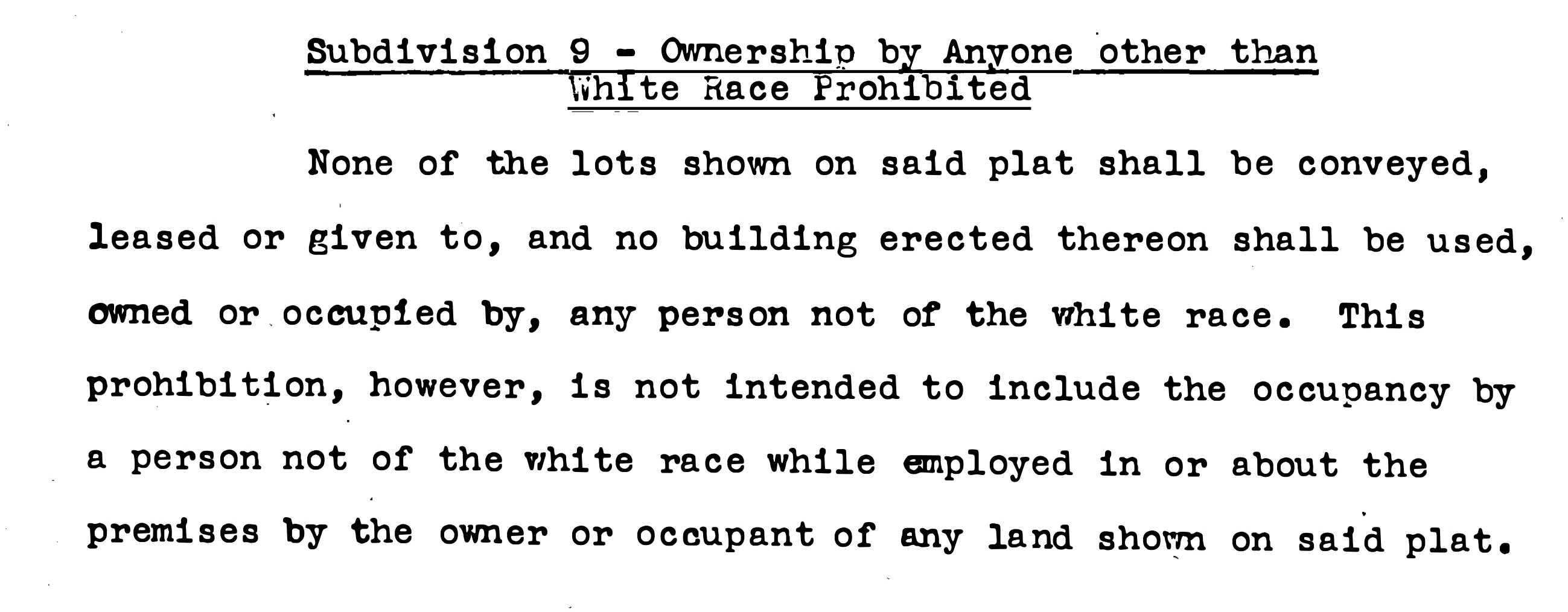

Detail from one of the subdivision restrictions filed by the Long-Bell Company

Detail from one of the subdivision restrictions filed by the Long-Bell Company

While these advertisements mentioned restrictions without specifying their racialized meaning, the language used in the over 8,000 restrictions found in Longview were far more explicit. Many used the following clauses which notably made an exception for domestic servants:

"None of the lots shown on said plats shall be conveyed, leased or given to, and no building erected thereon shall be used, owned or occupied by, any person not of the white race. This prohibition, however, is not intended to include the occupancy of a person not of the white race while employed in or about the premises by the owner or occupant of any land shown on said plat."

A large portion of the restrictions were recorded in the first years of Longview’s existence, meaning that racial exclusion was built into the town’s DNA from the very beginning. Eighty percent of the restrictions were imposed by Long-Bell Corporations and its subsidiary companies–the Longview Company and the Longview Suburban Company. Outside of Longview, additional covenants were recorded by other companies and property owners. Wesley Vandercock, head engineer of the Long-Bell Company, restricted over 200 properties in Kelso in 1928.

The practice of recording new restrictions continued for three decades. Long-Bell Lumber Company recorded the last known restriction in Cowlitz County in 1953.

Lumber and destiny

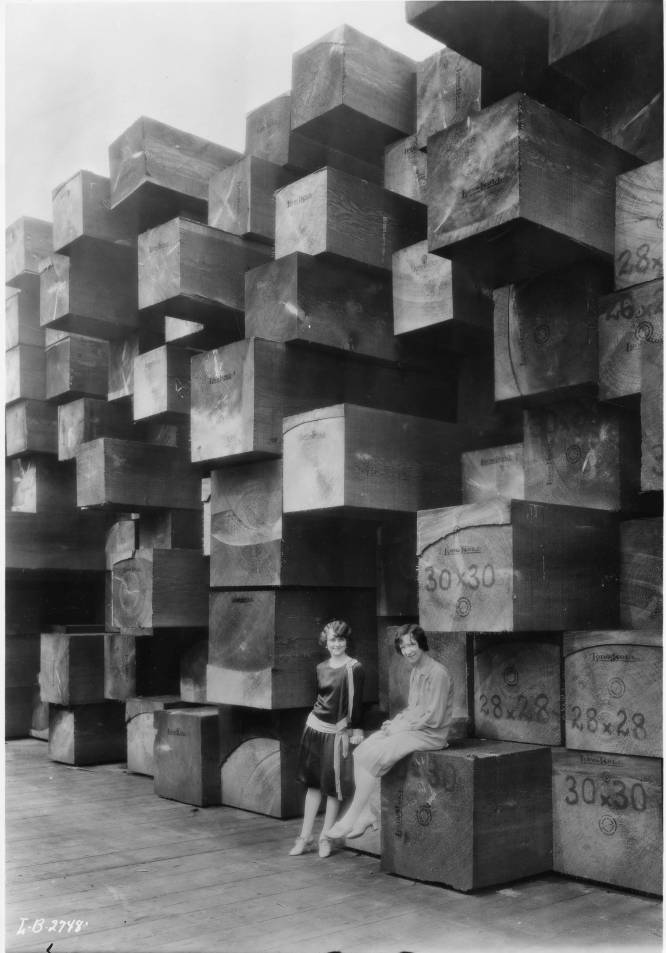

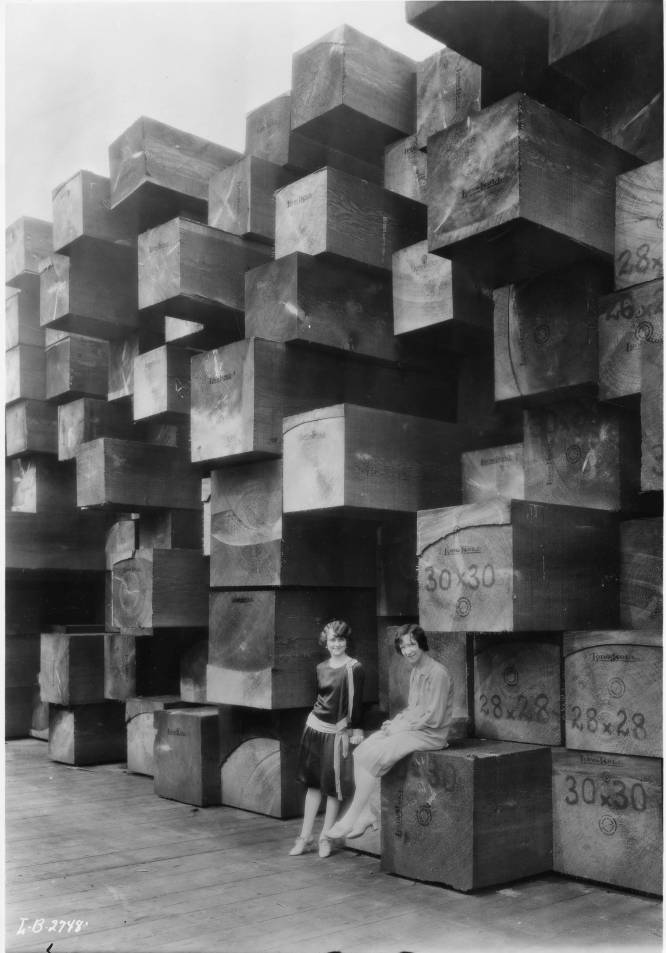

"a pile of super giant "Jap squares" Japanese squares on the Long-Bell export docks... ready for shipment to Japan." 1928 (courtesy Longview Public Library).

"a pile of super giant "Jap squares" Japanese squares on the Long-Bell export docks... ready for shipment to Japan." 1928 (courtesy Longview Public Library).

Longview was envisioned to be the next great American city and was, as such, initially built for a population of 50,000. Yet, today the population is less than 38,000. While R.A. Long was largely successful at keeping Longview white, his dream of an ever growing lumber company and civic development to match it fell short at multiple points in the town's history. Longview had a short period of prosperity following its construction as other companies opened mills and factories in the town. These included the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company and the Longview Fibre Company.[18] Huge volumes of lumber also flowed out of the local international port, most of which was sent to Japan.[19]

The Great Depression interrupted the first decade of growth. Even before the Depression started, Long-Bell was already in a vulnerable financial position because the market for timber had softened. The crisis worsened as the national and global economy collapsed. In 1932, Long-Bell sold off their electrical plant and their portion of the Longview, Portland and Northern Railroad (LP&N) for a total of $7.2 million dollars. Just one year later, the Cowlitz River flooded and destroyed sections of the LP&N which would never be fixed due to previous low profitability. Then, in 1934, R.A. Long died just as the Long-Bell Company was declaring bankruptcy. The company’s proposed reorganization plan in 1935, allowed it to survive the Depression.[20] By 1940, things started looking up as the Reynolds Metals Company started operations in Longview. This move was in large part due to the outbreak of WWII and the increased need for aluminum and lumber.

While the financial situation in Longview improved during the war, the county’s tiny Japanese population suffered the fate of Japanese Americans up and down the west coast. [21] Prior to WWII, 38 Japanese Americans were employed by Long-Bell and were forced to live in their own community near mill shipping sheds.[22] In 1942, they joined 120,000 other Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in internment camps under Executive Order 9066.[23]

Growth had finally returned to Longview for the first time in 20 years, as workers flocked to fill open positions at the Reynolds Aluminum plant, but the wartime population boom still fell short of the expected population of 30,000. In 1956, Long-Bell executives knew the company was in trouble and decided to merge with the International Paper company. By 1960, the so-called “infinite” supply of old-growth fir and cedar owned by Long-Bell had finally been depleted. With no trees to process, the old Longview mills closed their doors.

The end of the Long-Bell Company did not bring about the end of Longview, as some worried. Longview continued to grow during the period between 1960 and 2000 as Weyerhaeuser, the Longview Fibre Company, and the Reynolds Metals Company expanded production.

Demographics Through the Decades

Despite the irreparable harm to communities of color caused by Mr. Long, he has been touted as a wise and generous philanthropist for whom deserves the gratitude and respect of the entire Longview community. Many cite the fact that he personally owned and established the local Y.M.C.A., church, and newspaper. Other public services, such as schools, community centers, hospitals, and the public library were donated to Longview by the Long-Bell company. A closer look at historic photos taken of these public facilities, as well as other community gatherings and clubs in the area, are quite telling of who Longview was made for.

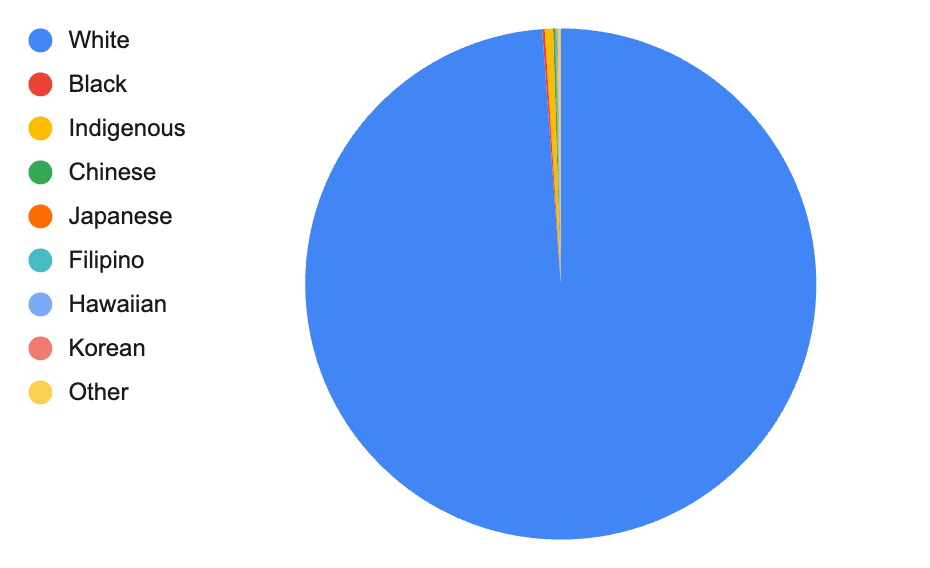

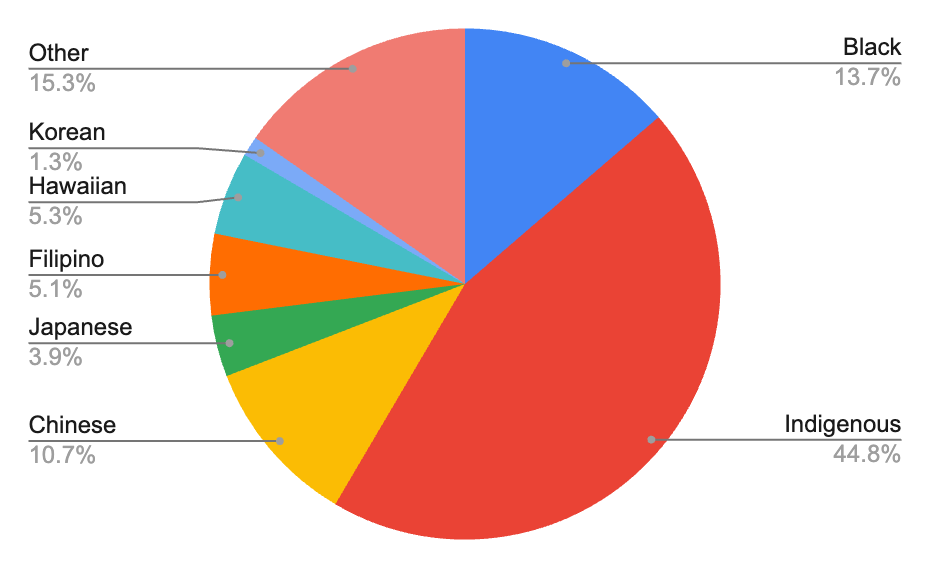

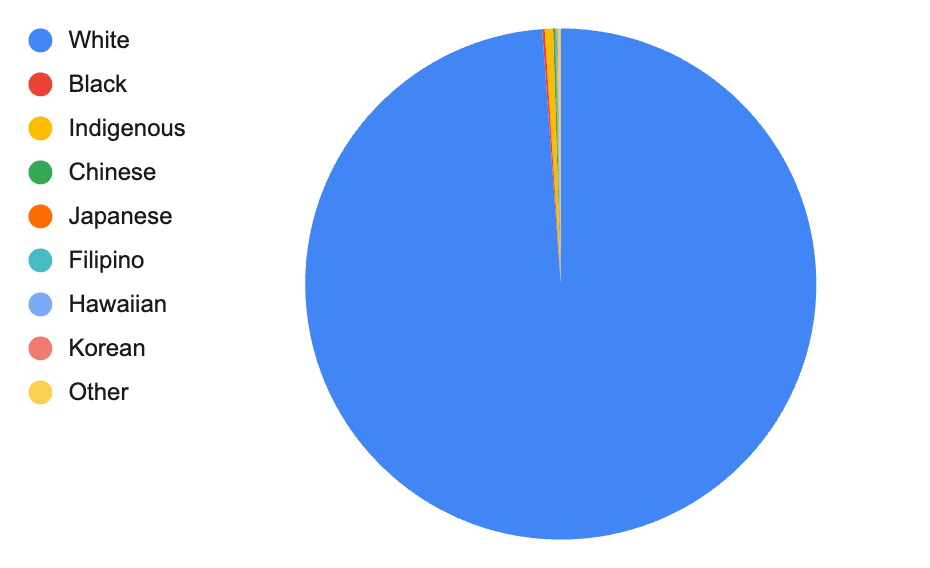

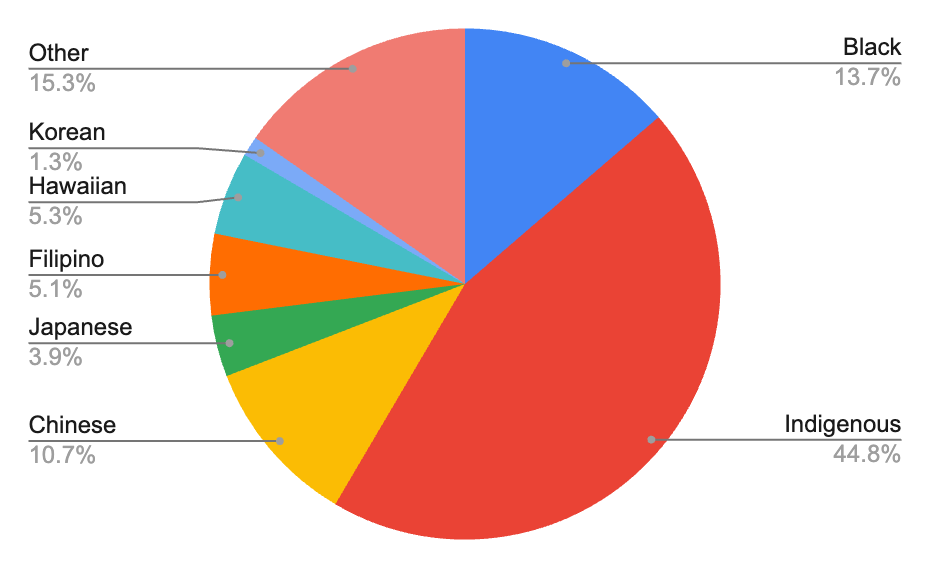

1970 county population by race. Top chart shows that whites were 98.8% of the population. Lower chart shows the distribution of the tiny number of nonwhites living in Cowlitz in 1970

1970 county population by race. Top chart shows that whites were 98.8% of the population. Lower chart shows the distribution of the tiny number of nonwhites living in Cowlitz in 1970

Decade by decade census data show that the city and county excluded persons of color. In 1930, following the building boom and energetic promotion of RA Long's new city, the total population of Cowlitz County was 31,906 while the non-white population was only 229, making the county 99.3% white.[24] By the 1940’s, the total population increased past 40,000 of whom only 241 were nonwhite -- 75 of them Black. In the 1950’s, the total non-white population actually decreased to pre-1930’s levels, leaving the county 99.6% white. By 1960, the non-white population rose slightly to 332 with the total population still 99.4% white.

The 1970 census data was more detailed which gives us a better understanding of the specific racial makeup of Cowlitz County. The two charts to the right paint a very striking image. The first puts into scale just how white Cowlitz really was. The second chart tells us that Indigenous Americans made up the largest percentage of the non-white population followed by Black, Chinese, Hawaiian, Filipino, Japanese, and Korean individuals.

In the last thirty years the demographics of the county have begun to change, mostly as Latinos have moved into the area. In the 2000 census, 4,321 Latinos were counted along with 1417 Native Americans, 482 African Americans, and 1,330 Asian Americans. The county remained 92% white. In the most recent 2020 count, the number who said they were Hispanic/Latino had more than doubled and while the number of Black and Asian residents had increased only modestly, more than 10,000 residents now said they were multiracial (two or more races). Those saying they were non-Hispanic white had dropped to 79%. This was a whiter distribution than the state as a whole but a substantial departure from the county’s long history of racial exclusion.[25]

What is Kept Hidden Should be Revealed

Timber for export, Port of Longview on Columbia River, with city of Longview behind, 2008 (photo: Sam Beebe, Wikipedia)

Timber for export, Port of Longview on Columbia River, with city of Longview behind, 2008 (photo: Sam Beebe, Wikipedia)

It is true that, as one of the nation’s only planned cities, Longview is incredibly unique and rich with history. Walking through the spotless streets, surrounded by historically designated colonial style buildings, perfectly green parks, and rows of family owned businesses it is hard not to feel nostalgic for a time that once was. Families surely feel at ease raising their children in such a quiet and walkable town: a place with personality. Under the surface, that personality is one of colonialism, environmental degradation, corporate domination, and racial exclusion all under the thin veil of the white American dream. The price of R.A. Long’s failed experiment is still being paid by those he hoped to exclude. With the entry to homeownership becoming unattainable to those without generational wealth, the interest rate on that experiment only grows. The scar of racial segregation is still fresh and will only begin to heal once Longview recognizes who their beloved founder truly was and how his legacy is continually perpetuated to this day. Desegregation has been a slow and uneven process across the nation and there is no place where that is more visible than Longview, Washington.

Ari Bleu Conboy is Research Associate for the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project

[1] Roy I. Rochon Wilson [Itswoot Wawa Hyiu - Bear Who Talks Much], History of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, 2nd Edition (Gorham Printing, 2021), 1.

[2] Roy I. Rochon Wilson [Itswoot Wawa Hyiu - Bear Who Talks Much], History of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, 2nd Edition (Gorham Printing, 2021), 2.

[4] HistoryLink. “Donation Land Claim Act, Spur to American Settlement of Oregon Territory Takes Effect on September 27, 1850,” n.d. https://www.historylink.org/file/9501.

[5] “Longview -- Thumbnail History,” HistoryLink, n.d., https://www.historylink.org/file/8560.

[6] Jim Tweedie and The R.A. Long Historical Society, The Long-Bell Story, 1st Edition (Param Press LLC, 2014), 27.

[7] John M. McClelland Jr., Longview: The Remarkable Beginnings of a Modern Western City, Silver Jubilee Edition (Portland, Oregon, United States of America: Binford & Mort, 1949), 1.

[8] John M. McClelland Jr., Longview: The Remarkable Beginnings of a Modern Western City, Silver Jubilee Edition (Portland, Oregon, United States of America: Binford & Mort, 1949), 6.

[9] John M. McClelland Jr., Longview: The Remarkable Beginnings of a Modern Western City, Silver Jubilee Edition (Portland, Oregon, United States of America: Binford & Mort, 1949), 10.

[10] “Longview -- Thumbnail History,” HistoryLink, n.d., https://www.historylink.org/file/8560.

[11] John M. McClelland Jr., Longview: The Remarkable Beginnings of a Modern Western City, Silver Jubilee Edition (Portland, Oregon, United States of America: Binford & Mort, 1949), 21.

[12] Oliver H. Heintzelman, Longview, Washington—A Planned City, Journal of Geography 57 (January 1, 1958), 183–89.

[13] Lisa Curdy, “Hundreds Flock to Praise Local Civil Rights Leader,” Longview Daily News, January 19, 2004, https://tdn.com/news/hundreds-flock-to-praise-local-civil-rights-leader/article_5a9d4302-d912-5811-9076-46dce279ee84.html.

[14] Brennen Kauffman, “Homer Plessy, Key to &Quot;Separate but Equal,&Quot; on Road to Pardon,” March 18, 2023, https://tdn.com/news/local/longview-adding-plaque-about-victoria-freemans-life-to-park-named-after-her/article_44669792-c4f4-11ed-988c-87404178a413.html.

[15] Sydney Brown, “WATCH: Longview Staff Give Updates on the Monticello Convention Historical Site,” July 30, 2023, https://tdn.com/news/local/education/article_57f512ce-21ca-11ee-8c25-4b563fb41740.html.

[16] Lisa Curdy, “Hundreds Flock to Praise Local Civil Rights Leader,” Longview Daily News, January 19, 2004, https://tdn.com/news/hundreds-flock-to-praise-local-civil-rights-leader/article_5a9d4302-d912-5811-9076-46dce279ee84.html.

[17] Longview Company, Longview, Wash., Longview, Washington, an Ideal Industrial City, a Wonderful Place to Live., n.d., 11.

[18] “Longview -- Thumbnail History,” HistoryLink, n.d., https://www.historylink.org/file/8560.

[19] Jim Tweedie and The R.A. Long Historical Society, The Long-Bell Story, 1st Edition (Param Press LLC, 2014), 40-41.

[20] “Longview -- Thumbnail History,” HistoryLink, n.d., https://www.historylink.org/file/8560.

[21] Virginia Urrutia, They Came to Six Rivers : The Story of Cowlitz County, 1998, 182.

[22] Jim Tweedie and The R.A. Long Historical Society, The Long-Bell Story, 1st Edition (Param Press LLC, 2014), 109.

[23] “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration,” National Archives, January 24, 2022.

[24] Population data for this section is from National Historic Geographic Information System (IPUMS-NHGIS)

.png)

Detail from 1876 map by Department of the Interior showing original tribal territories. Notice that area shown as Kowlitz territory includes no land designated as a tribal reservation (Library of Congress). Click to enlarge.

Detail from 1876 map by Department of the Interior showing original tribal territories. Notice that area shown as Kowlitz territory includes no land designated as a tribal reservation (Library of Congress). Click to enlarge. Bust of R.A. Long erected in 1942, eight years after his death (photo: Kearby Chess, Wikipedia).

Bust of R.A. Long erected in 1942, eight years after his death (photo: Kearby Chess, Wikipedia).  Marketing the new city involved advertizing in newspapers and magazines and on billboards up and down the west coast. This full page promotion was published in 1926. Click for larger version. (courtesy, University of Washington Special Collections)

Marketing the new city involved advertizing in newspapers and magazines and on billboards up and down the west coast. This full page promotion was published in 1926. Click for larger version. (courtesy, University of Washington Special Collections)  Click to see interactive map showing racial restrictions in most neighborhoods of Longview, restricting more than 8,000 properties.

Click to see interactive map showing racial restrictions in most neighborhoods of Longview, restricting more than 8,000 properties.

8th grade class photo from Kessler school in 1950 shows that the city's so-called integrated school system was predicated on the fact that there were only a handful of nonwhite students living in the city. (Courtesy: Longview Public Library)

8th grade class photo from Kessler school in 1950 shows that the city's so-called integrated school system was predicated on the fact that there were only a handful of nonwhite students living in the city. (Courtesy: Longview Public Library) Detail from one of the subdivision restrictions filed by the Long-Bell Company

Detail from one of the subdivision restrictions filed by the Long-Bell Company "a pile of super giant "Jap squares" Japanese squares on the Long-Bell export docks... ready for shipment to Japan." 1928 (courtesy Longview Public Library).

"a pile of super giant "Jap squares" Japanese squares on the Long-Bell export docks... ready for shipment to Japan." 1928 (courtesy Longview Public Library).

1970 county population by race. Top chart shows that whites were 98.8% of the population. Lower chart shows the distribution of the tiny number of nonwhites living in Cowlitz in 1970

1970 county population by race. Top chart shows that whites were 98.8% of the population. Lower chart shows the distribution of the tiny number of nonwhites living in Cowlitz in 1970  Timber for export, Port of Longview on Columbia River, with city of Longview behind, 2008 (photo: Sam Beebe, Wikipedia)

Timber for export, Port of Longview on Columbia River, with city of Longview behind, 2008 (photo: Sam Beebe, Wikipedia)