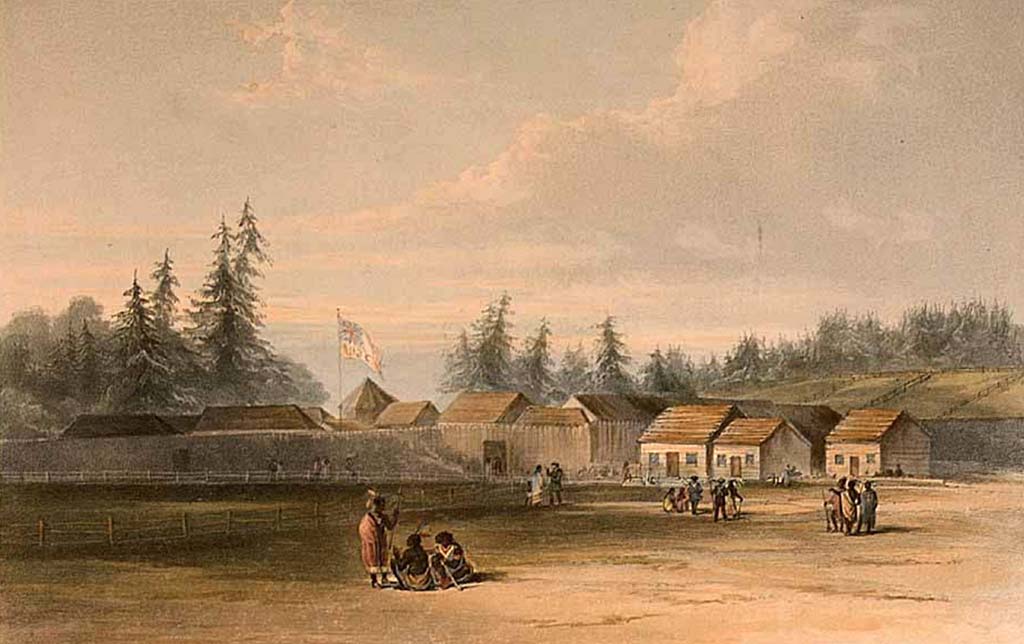

Vancouver is proud of its history. Clark County takes its name from William Clark co-leader of the overland expedition that established the US claim to the Pacific Northwest. A few years after the Lewis and Clark visit, Fort Vancouver was built by the Hudson Bay Company, serving for decades as the most important settlement in the region and attracting traders and settlers from many lands. Residents know too about other episodes of population growth, including World War II when thousands came to work in the shipyards and build troop ships, transport vessels, and escort aircraft carriers for the war in the Pacific.

Less well known is the county’s history of exclusion and the racial criteria that made only White people welcome for many generations. As late as 1970 the county population was 99% White and was still 95% White in 1990. This essay tracks that history, exploring sequences of racial exclusion and detailing practices that were used against people of color, practices that included racial restrictive covenants and an effective campaign to expel Black residents after World War II.

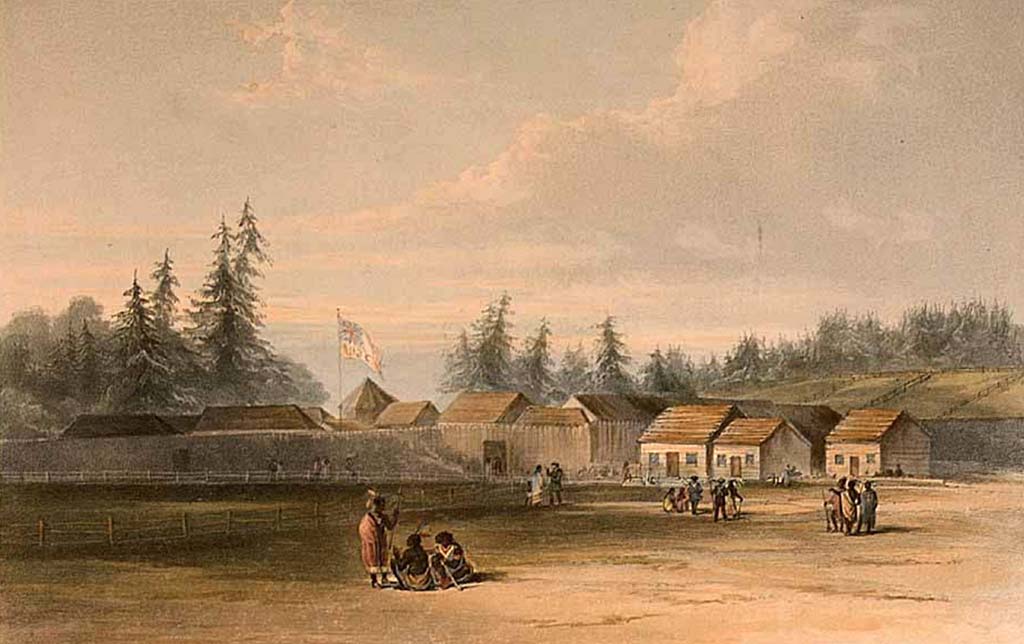

Fort Vancouver, 1845, sketch by Lt.Henry Warre (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries Digital Collection)

Fort Vancouver, 1845, sketch by Lt.Henry Warre (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries Digital Collection)

The first expulsion

For millennia what would later become Clark County was home to Chinook, Cowlitz and Klickitat peoples. The British Hudson Bay Company established Fort Vancouver, the first permanent European base in the Pacific Northwest, in 1824. By 1846 when the United States and Britain settled their colonial claims, the Indigenous population had been decimated by smallpox and other diseases and partially replaced by settlers and traders from distant lands.[1] The majority were White U.S. born citizens. Others were French-Canadian, English, Scottish, Iroquois, and Hawaiian.[2] The Hawaiian population was particularly large and by 1844 constituted around 30% of the total population, nearly 138 total native Hawaiians.[3]

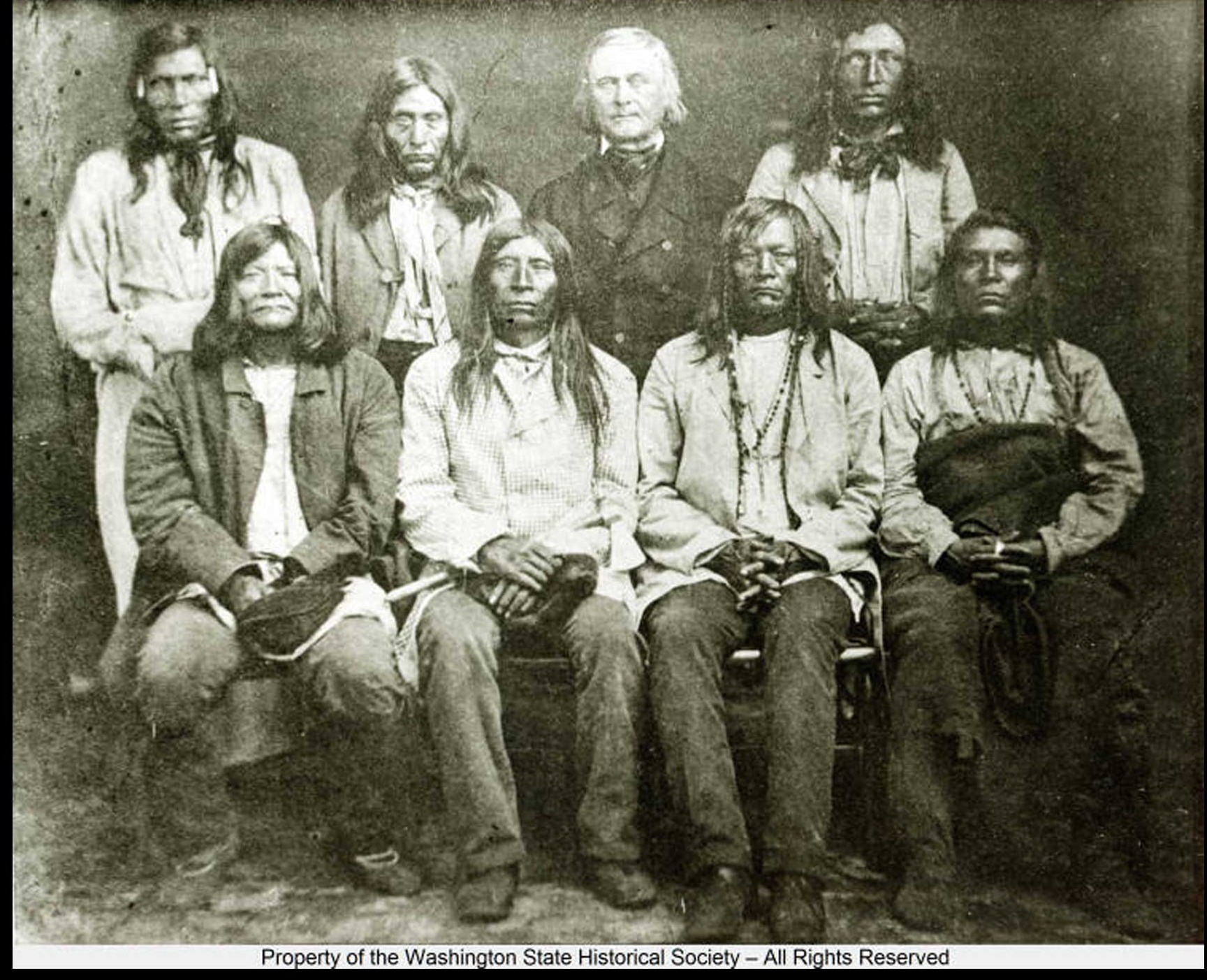

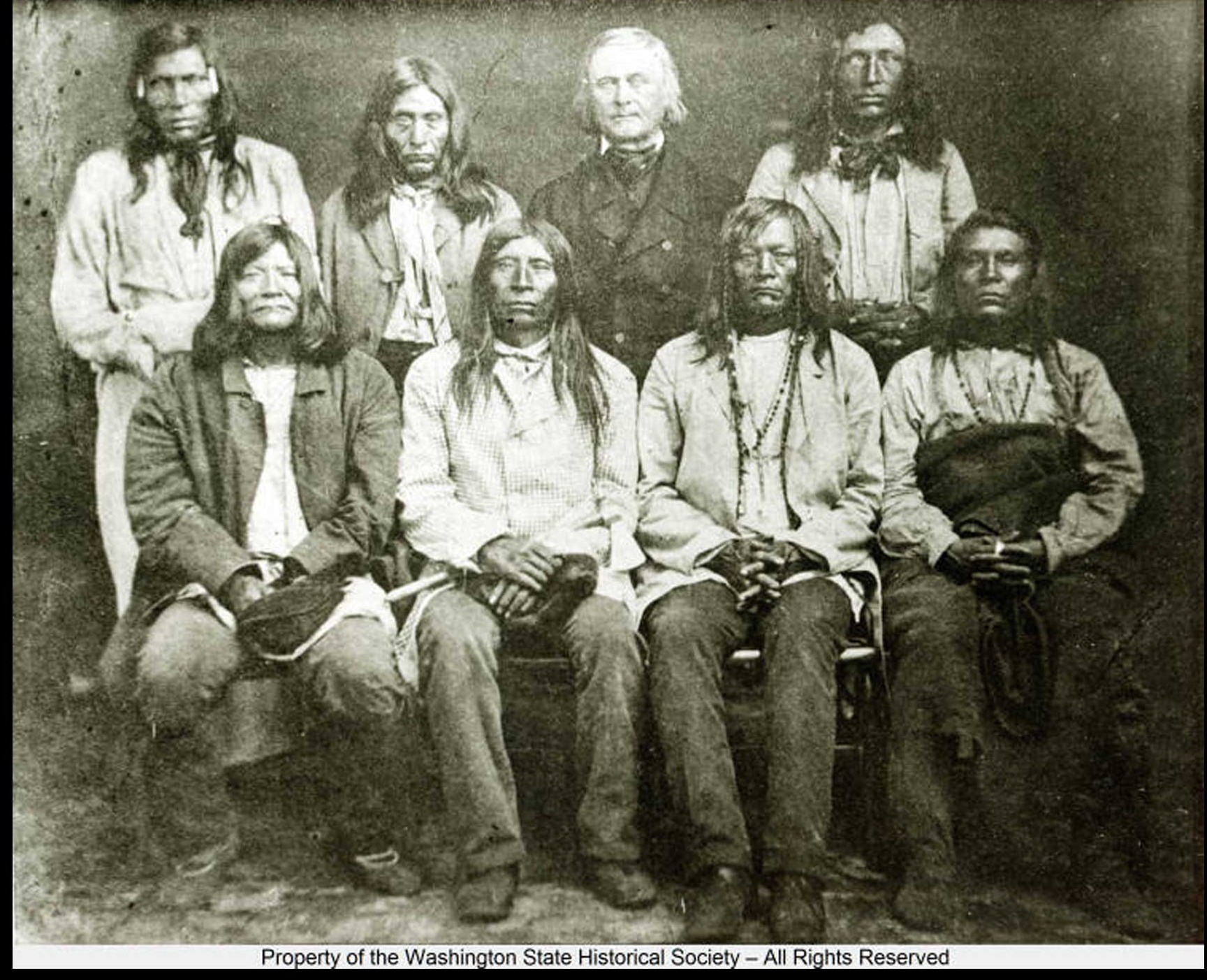

After the US took control and created Washington Territory, the surviving Indigenous peoples faced new threats. Appreciating its critical location on the Columbia River, the US Army established its most important installation at Fort Vancouver, later renaming it Vancouver Barracks. Troops were dispatched from there during the many “Indian wars” that followed, and Indigenous prisoners were held in its stockades, including the seven chiefs of the Kalispets, Colville, Coeur D’Alene, and Flathead nations who surrendered in 1856.[4]

Chiefs of the Kalispets, Flathead, Colville, and Coeur D’Alene nations after surrending at Fort Vancouver, 1856. Photo F. Aldrich. Washington State Historical Society.

Chiefs of the Kalispets, Flathead, Colville, and Coeur D’Alene nations after surrending at Fort Vancouver, 1856. Photo F. Aldrich. Washington State Historical Society.

Before that in 1854-55, territorial Governor Isaac Stevens dictated treaties expropriating nearly all lands from Indigenous tribes and assigning them to small reservations. The Chinook and Cowlitz people were left without even that. In 2010, 165 years later, the Cowlitz tribe finally won the right to their own small reservation. The Chinook tribe remains without federal recognition.

The county population grew slowly in the next half century, reaching a total of 13,429 in 1900, 99.3% of them White. Only 20 Indigenous Americans were counted in that census along with 10 African Americans and 62 other nonwhites. [5]

When the Interstate Bridge across the lower Columbia opened in 1917, Vancouver assumed a new role in the expanding road and streetcar system leading to Portland, becoming in time more connected to northern Oregon than to its own state. World War I shipyards added an industrial base and attracted new population. But again, only Whites were welcome. The 1940 Clark County population of 49,852 included only 182 persons of color, including 18 African Americans.[6]

_about_to_be_launched_on_5_April_1943_(NH_75634)-wiki.jpg) USS Casablanca, an escort carrier (baby flattop), about to be launched in Kaiser shipyard, 1943 (Wikipedia)

USS Casablanca, an escort carrier (baby flattop), about to be launched in Kaiser shipyard, 1943 (Wikipedia)

Kaiser Shipyards

World War II opened a different story. Between 1940 and 1950, internal migration from southern and eastern states increased the population of Washington by 28.6% - one of the largest increases it had seen.[7] Most of the growth occurred during the war years and centered on locations with defense industries or military bases. Vancouver had both and experienced a dramatic population increase.

“For the small town of just under 19,000, the Kaiser Shipyard boom came like a thunderstorm,” writes historian Donna Sinclair. [8] According to surveys conducted by the Washington State Census Board, Vancouver’s population more than doubled between 1940 and 1945, reaching 39,500, while the county population soared above 90,000. Most of the newcomers found work at the Kaiser Shipyards along the Columbia River.

The majority of the new residents were White, but more than 8,000 African Americans arrived from the South or Midwest. For Black people, the United States’ entrance into WWII sparked an opportunity for stable work in an otherwise unstable world.[9] With such a large population increase, it would be the largest number of Black residents the city would ever see.

Theodie Chapman Owens was one of the African American newcomers. Originally from Decatur, Alabama, she made the two-thousand-mile trek in 1943 with her two young daughters after hearing about the economic opportunities Kaiser offered.[10] A rather turbulent time in her life, Owens saw this trip as a way to start anew. She had recently lost her father, divorced her husband, and left behind her eldest son so that he could help his grandmother. The Kaiser shipyards would be Theodie Owens’ first paying job, and for her two daughters it was a fun adventure to a new place, far away from the turbulence that had seeped into their lives.

The Owens are just one example of thousands. Kaiser had plenty of benefits for Black workers including higher wages than had been available before the war. Many of the Black workers who moved to the west coast were from the south, and as such were used to Jim Crow laws and lack of opportunities. However, if they expected to escape discrimination, life in Vancouver would prove otherwise. African Americans would face challenges on both the personal and broader societal level both in and outside the job.

Joseph Harrison, a young man from Wilcox County, Alabama, made his way to Vancouver during the early war years. A jack-of-all trades, Harrison was able to pick up any skill with proficiency and elegance, a trait he acquired from his grandfather. After attending welding school, Harrison was hired at Kaiser and proved a talented welder. During this time, Kaiser had introduced an innovative system known as prefabrication, which would assign more workers for individual tasks at every level of production.[11] This system allowed for rapid advancement through the ranks for many workers, and with his demonstrated skills Joseph Harrison should have been a shoe-in. However the boilermakers’ union, which oversaw much of the west coast shipyard workers, did not allow Black workers into their ranks.[12] Harrison was denied promotions and the security of union protections. Kaiser’s shipyards hired Black workers, but blatant racial discrimination still persisted.

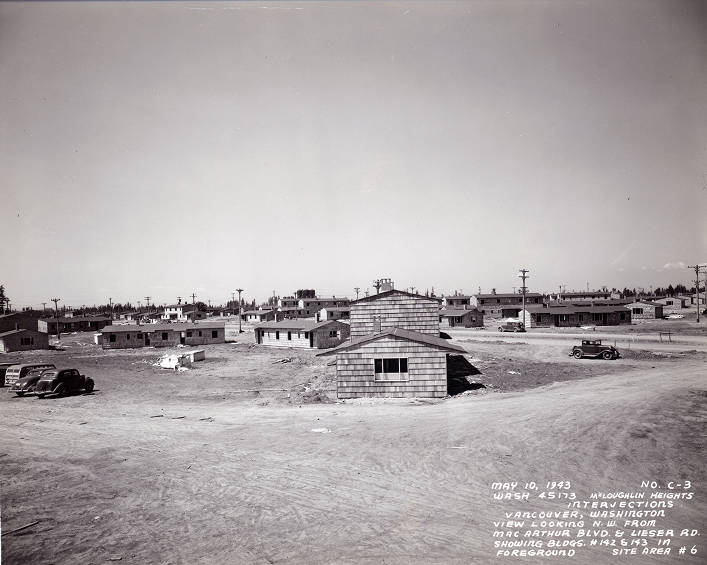

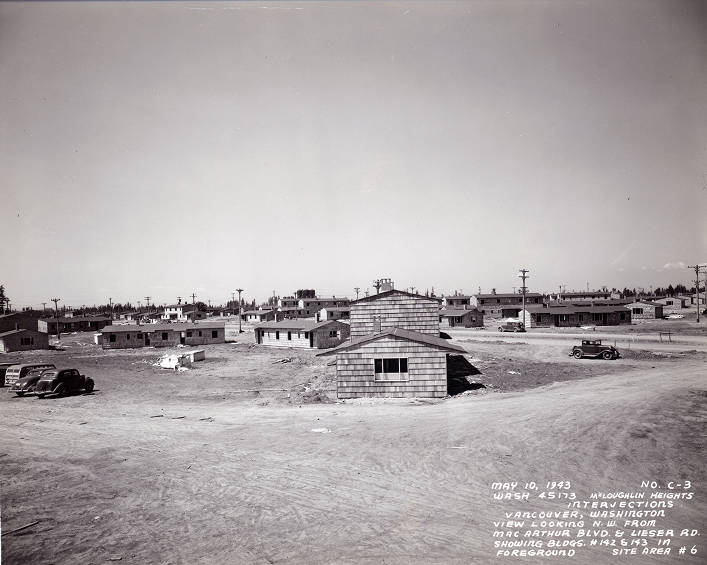

New defense housing under construction in Vancouver (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

New defense housing under construction in Vancouver (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

Housing was another challenge. As Vancouver’s population soared where would the newcomers live? With federal funds, Kaiser initially built emergency dormitories. That was just the start of a massive building effort. According to a 1945 report on wartime housing built by the Federal Public Housing Authority (FPHA), nearly 314,000 temporary units were constructed across the county, 16,000 in Clark County, ultimately providing housing for nearly 60,000 people.[13]

Some were dormitories for single workers, but the vast majority, around 12,291, were family units, typically duplexes or free-standing houses. They were sited in brand-new subdivisions to the east and west of Vancouver’s existing neighborhoods and became neighborhoods themselves with parks, schools, and community buildings. The largest was McLoughlin Heights, a 1,000 acre track of winding streets with more than 6,000 housing units in unincorporated Clark County east of Vancouver. As large as the city itself, the new suburb eventually included a shopping center, three schools, a community center and other facilities serving 25,000 people.[14]

Early in 1942, Vancouver authorities created the Vancouver Housing Authority (VHA) under the first chairman D. Elwood Caples to work with the federal agency and oversee the development of housing for workers “‘engaged in national defense activities.’”[15] These housing projects were supposed to accommodate Black as well as White workers and families. In practice, African Americans faced discrimination.

In 1942, there were few openings in Vancouver projects for Black workers and families. Instead, they commuted across the Columbia River from segregated complexes on Vanport island where Kaiser had another shipyard complex. [16]

As new projects opened in 1943, Black families applied and were accepted. L.C. Kelly recalled that most Housing Authority Projects seemed to be segregated, with Black residents living in pockets.[17] The VHA denied any segregation, stating tenants were assigned housing based on their arrival to Vancouver, and as such pockets did indeed form but not based on race.[18] Despite such claims, in fact most Black families were assigned to segregated clusters especially in McLoughlin Heights.

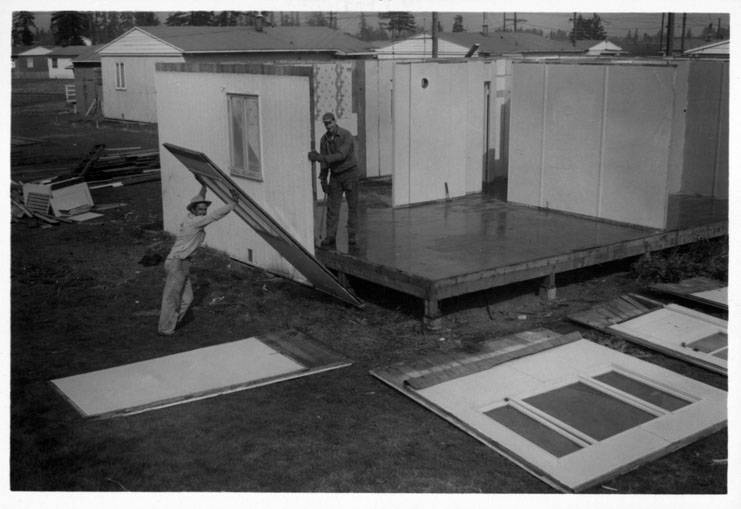

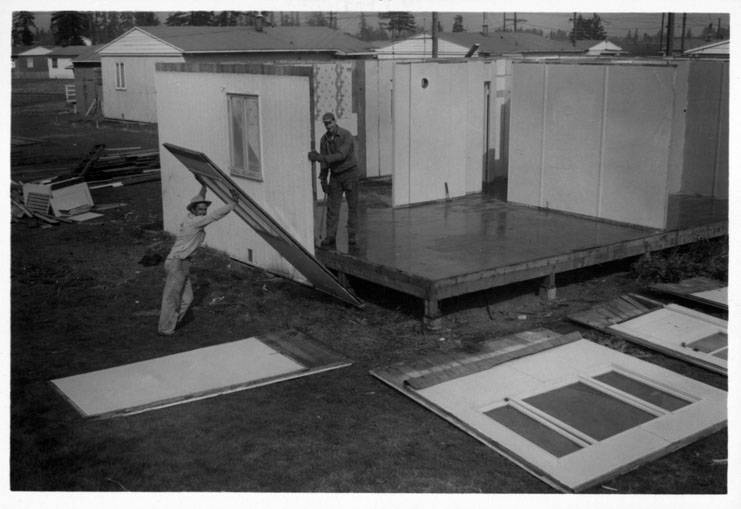

Walls come down in a house decommissioned by the Vancouver Housing Authority, 1957 (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

Walls come down in a house decommissioned by the Vancouver Housing Authority, 1957 (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

Demolishing public housing

The VHA never intended for the vast majority wartime housing to be permanent and thus began to decommission them as the war ended. They did this utilizing what became known as the “Vancouver Plan”, which focused on transforming the city into a prosperous and bustling postwar community.[19] The plan envisioned demolishing wartime housing to put in place middle-class neighborhoods and avoid slums, something planners worried would happen if public housing remained. Most White residents praised this, fearing low-cost housing would attract poor residents. Vancouver’s NAACP condemned the plan for not including Black citizens. Their worries were valid. In the years ahead the dismantling of the public housing projects would lead to the destruction of Vancouver’s Black community and the effective expulsion of most African American residents. By 1970, only 428 African Americans remained in Vancouver, just remnants of a population that exceeded 8,000 in 1945.[20]

A 1945 survey that reveals the intentions of Clark County authorities. The VHA interviewed 1,200 out of the 1,730 Black families living in the federal housing projects to learn their intentions after the war and determine their suitability for moving out of the projects into the larger community. 57% of those surveyed said they would stay in Vancouver following the war while 24% said they would leave once employment ended.”[21]

Follow-up questions were revealing. Interviewers took specific note of education, personal appearance, and personality of Black interviewees. About a third of families questioned were deemed “above average” and “likely to adjust.”[22] The questionnaire reveals that the housing authority was worried. Worried not for Black families, but for White Vancouverites who saw permanent Black residents as a threat to a predominantly White city.

Federal planners had intended most wartime housing to be temporary. Of the over 16,000 total units built in Clark County, only 1,000 were meant to be permanent. In some other states and cities, temporary housing was maintained long after the war, continuing to provide for families who had trouble finding private housing. But VHS moved aggressively to dismantle most of its housing projects to avoid “the slums of the future,” coded language for marginalized populations.[23]

The “Vancouver Plan” called upon the federal government to donate to city and VHS more than 2,000 acres of federal land and housing, with VHS planning to preserve the permanent housing stock, nearly all occupied by White families, while clearing vast tracts of temporary housing and selling the land and to private developers. The evictions proceeded over the course of ten years, with the last units on McLoughlin Heights demolished in 1957.

An article in the Oregon Journal recorded the final stages noting that out of 8-10,000 Black residents in 1944, only 329 remained at the start of 1958. The article applauded signs that Vancouver was finally beginning to accept the tiny number remaining saying that “more of the Negro families stayed in Vancouver than in past years when they sought new housing; in 1956 only 4 of the 29 families that moved from the Heights stayed in Vancouver.”[24]

Jean Griffin and her family lived in McLoughlin Heights.[25] Griffin recalled in an interview the struggle her and her family faced trying to find private housing during the Heights gradual deconstruction:

"I remember when we got ready to move from The Heights there was a house over on the west side, near Kauffman Avenue. I didn’t like the place, it had a dirt basement, it was just an old bad-looking house. We called the people who were in charge of it and they said, “Well, we’ll have to call the owner to see if we can rent it.” They called us back in a few days and the man said no because he didn’t want to rent to blacks. It was the same way for getting jobs. They wanted us to leave the area. You couldn’t buy land or a house and that’s the way it was."[26]

Griffin’s story reveals the challenge that Vancouver’s Black population faced after the war. Pushed out of public housing, they confronted a wall of discrimination in the private housing sector. Few landlords would rent to people of color; few owners would sell; and entire neighborhoods of White residents were prepared to make life uncomfortable for any family who dared break the color line.

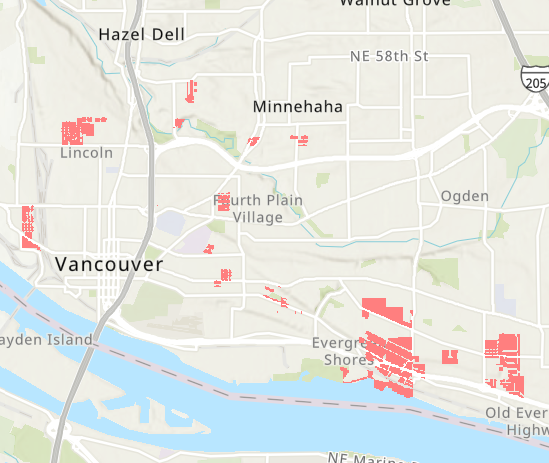

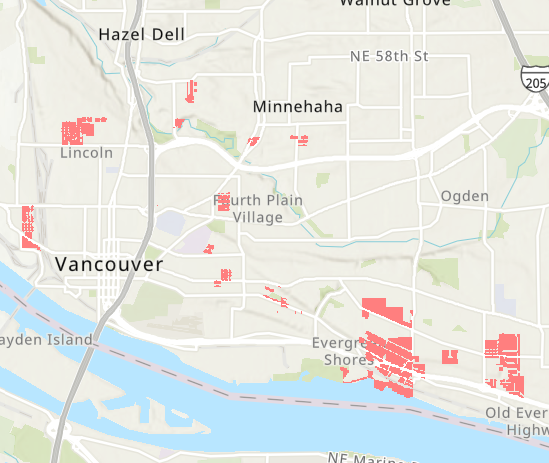

Click to visit interactive maps showing the location of properties marked by restrictive covenants.

Click to visit interactive maps showing the location of properties marked by restrictive covenants.

Racial Restrictive Covenants

Racial restrictive covenants were part of the apparatus of discrimination and exclusion. Our project has identified 34 subdivisions in and around Vancouver where properties were restricted on the basis of race. The term restrictive covenant refers to legal restrictions in deeds or other property records that are binding on future owners of a property, preventing them from selling, renting, or allowing occupation by persons of certain racial identities. The language imposed on properties in the Carson Heights subdivision in 1941 read:

“No person of any race other than the white or Caucasian race shall use or occupy any buildings on any of said lots.”

The developers of Telocaset subdivision used different language: "nor shall the same or any part thereof be in any manner used or occupied by Chinese, Japanese, or Negroes, except that persons of said races may be employed as servants by residents."

In some Washington counties, real estate professionals urged the use of restrictive covenants starting in the early 1920s, but the first in Clark County dates from 1928 with a few more recorded in the 1930s. The war fired up the real estate industry as developers rushed to subdivide land and build houses, and restrictive covenants became popular as a marketing tool ensuring White buyers that neighborhoods would forever bar people of color. In the 1940s, 32 new areas were racially restricted within Vancouver city limits. It is important to note that the most of these restrictions were implemented after 1942 when for the first time African Americans were seeking housing in Vancouver.

It is instructive to learn more about some of these restricted areas and the people who imposed the restrictions. Some of the leading citizens and key financial and industrial institutions in Vancouver were involved.

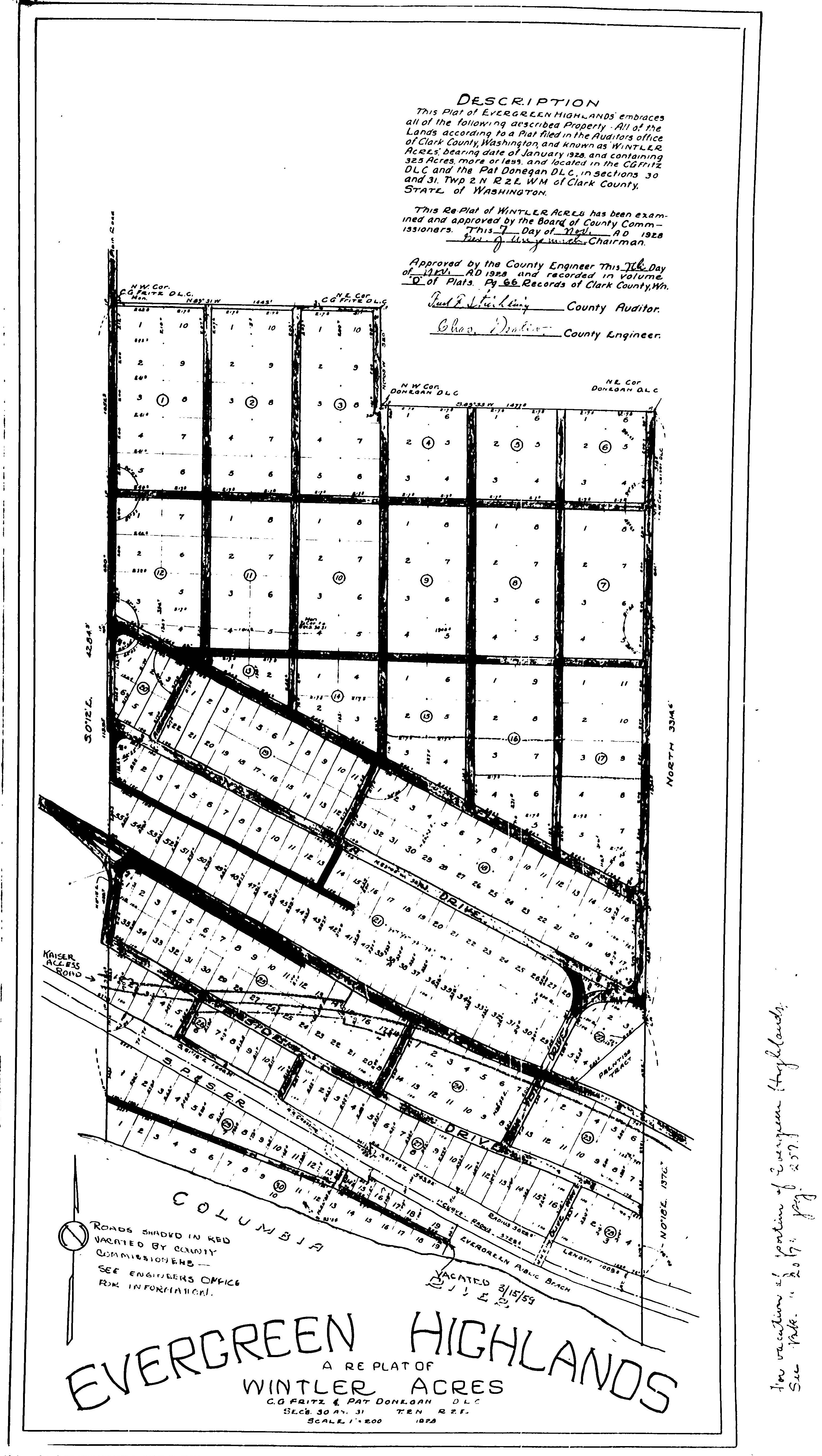

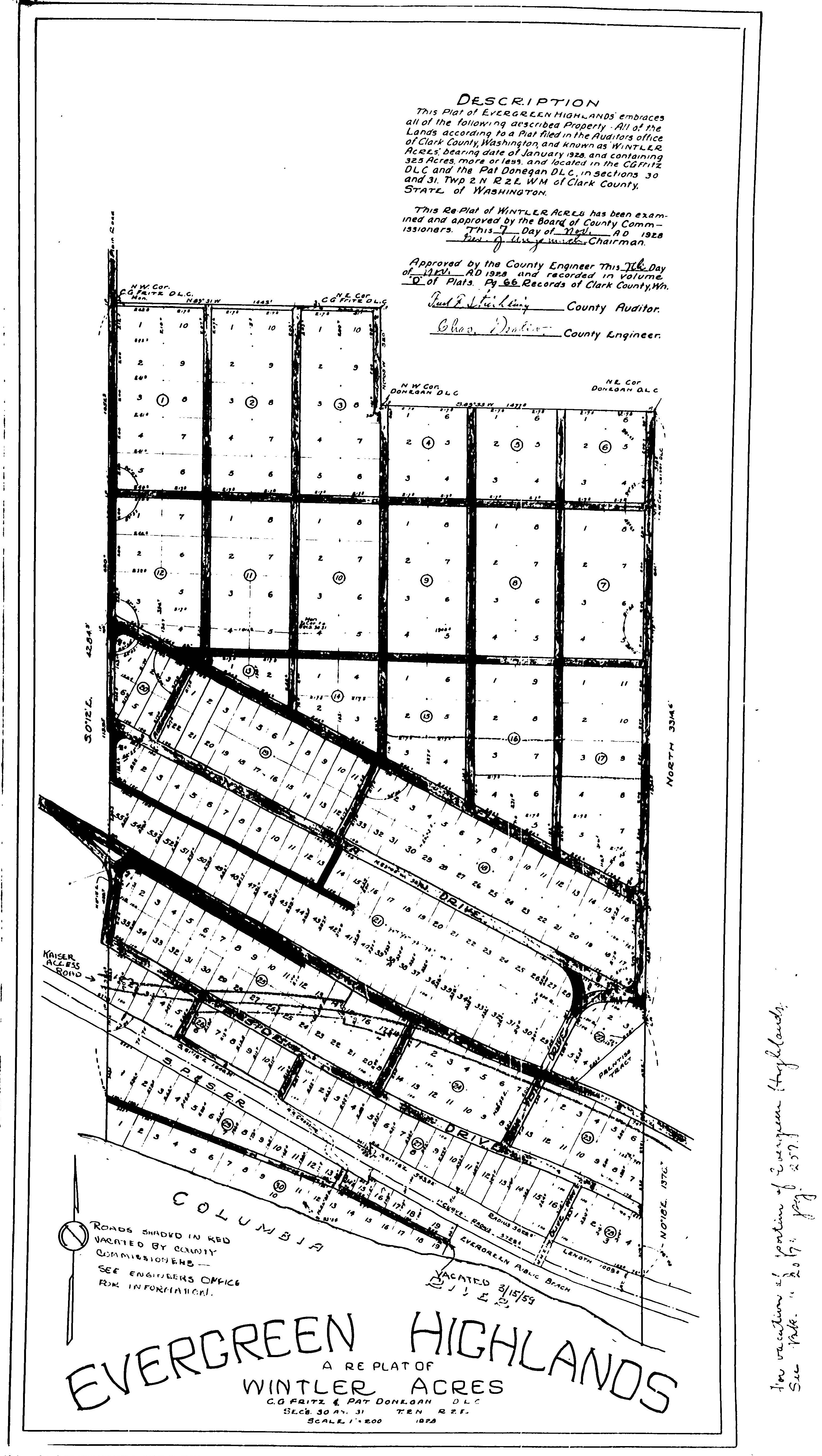

Plat map showing the roads, blocks, and nearly 400 parcels of Evergreen Highlands, east of Vancouver overlooking the Columbia. All parcels were sold with the following restriction "Grantees agree that they will not sell, lease or in any way dispose of the above described property to any person or persons not a member of the Caucasian Race, or to any society or societies whose members are not members 6f the Caucasian Race."

.

Plat map showing the roads, blocks, and nearly 400 parcels of Evergreen Highlands, east of Vancouver overlooking the Columbia. All parcels were sold with the following restriction "Grantees agree that they will not sell, lease or in any way dispose of the above described property to any person or persons not a member of the Caucasian Race, or to any society or societies whose members are not members 6f the Caucasian Race."

.

Platted in 1928, Evergreen Highlands was the first restricted subdivision we have identified. It was also the largest, involving 379 properties. It was developed and restricted by Wintler Acres Inc., whose president was Aloysius F. Lechtenberg. Lechtenberg settled in the Vancouver area in 1911 and operated a sawmill and a dairy farm.[27] At some point, Lechtenberg was on the Board of Directors of The First Independent Bank, which until 2011 was the county’s most famous bank, an indication of his prominence and importance to the area.

D. Elwood Caples was co-owner of Wintler Acres Inc. and appears as Secretary-Treasurer on the deeds and restrictions for Evergreen Highlands. Later he would lead the Vancouver Housing Association in charge of the demolition of public housing and expulsion of Black residents in the post-war period.

The Caples family were prominent figures in early 20th century Clark County, with D. Elwood Caples’ father being employed as a contractor, deputy county clerk, and the county Democratic chairman - a position his son would later also hold.[28] One of the most powerful men in Vancouver, the younger Caples would serve as attorney for Clark County’s Public Utilities before his appointment to lead the Vancouver Housing Authority in 1941, a position he retained for 35 years.

His early commitment to racial restrictive covenants matches well with his later commitment to the Vancouver Plan to demolish defense housing and expel Black families from Clark County. And it is instructive that in the many glowing accounts that have appeared over the years about these two leading citizens- Caples and Lechtenberg – there is no mention of their important role in the county’s history of racial exclusion.

Resistance

NAACP leaders: Front Row: Mark A. Smith and Perry Johniger; Second Row (Left to Right): Ozella McKinney, Bertha Baugh, Thelma Campbell and Henrie Lee Smith.(Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection: Collection No. 2007-1 Series 3; Box 3, Folder 18

NAACP leaders: Front Row: Mark A. Smith and Perry Johniger; Second Row (Left to Right): Ozella McKinney, Bertha Baugh, Thelma Campbell and Henrie Lee Smith.(Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection: Collection No. 2007-1 Series 3; Box 3, Folder 18

Black newcomers to what had been an all-White city faced discrimination in every sector their lives. Housing options were limited to the clusters of federal housing reserved for Blacks, especially McLoughlin Heights. Employment opportunities outside of the Kaiser yards generally meant custodial jobs. And the all-White Boilermakers union made sure that African American opportunities in the shipyards were limited. Meanwhile “Whites Only” signs kept them out of many cafes, bars, and recreational establishments.

Resistance developed quickly. Finding that they were not allowed in the union that represented Kaiser employers, Black workers organized the Shipyard Negro Organization for Victory and issued the following demands:

“We the Negro people employed by the Kaiser Company maintain that under false pretenses we were brought from east to west to work for defense, and we demand with due process of law, the following rights: (1) to work at our trades on equal rights with whites; (2) to go to vocational school or take vocational training on equal rights with whites.”[29]

In 1945, residents of the housing projects launched Vancouver’s first NAACP chapter.[30] With hundreds of chapters across the country, the NAACP was committed to addressing equal rights violations and fighting for opportunities.[31] Mark Smith, a radar technician at the Kaiser shipyards, became the chapter’s first president. Other inaugural members included Perry Johnigan, Joseph Harrison, Valree Joshua and William Baugh.[32]

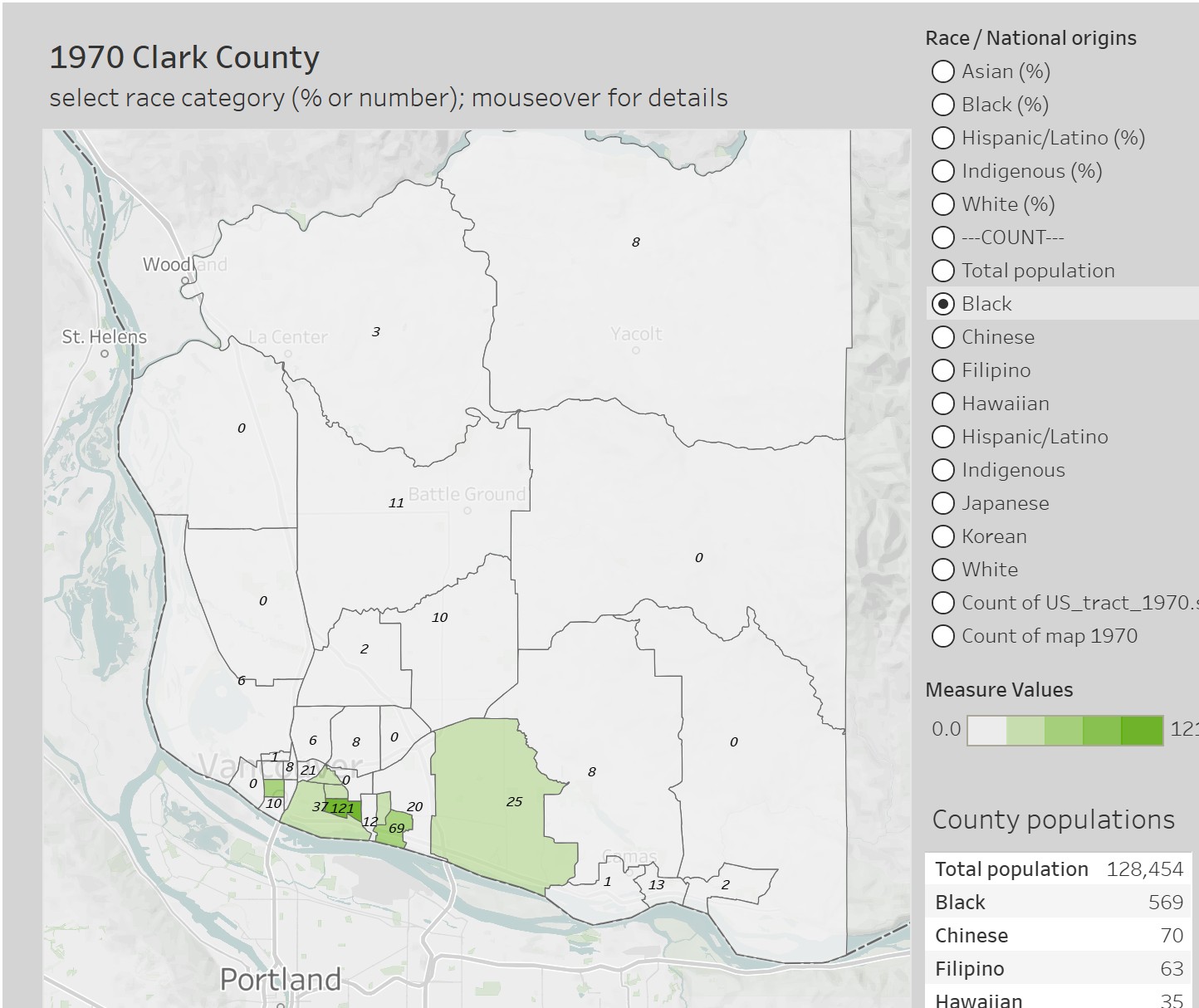

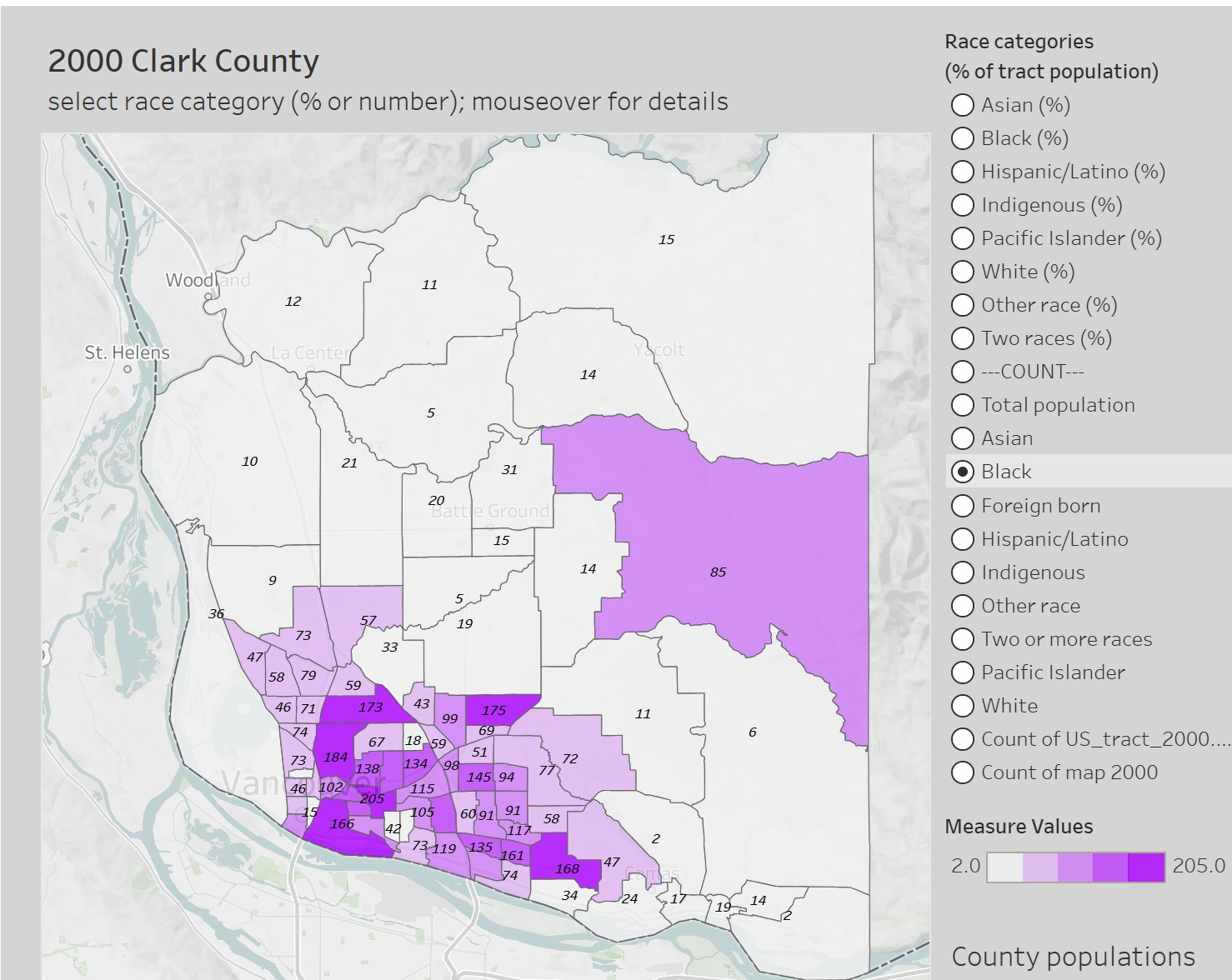

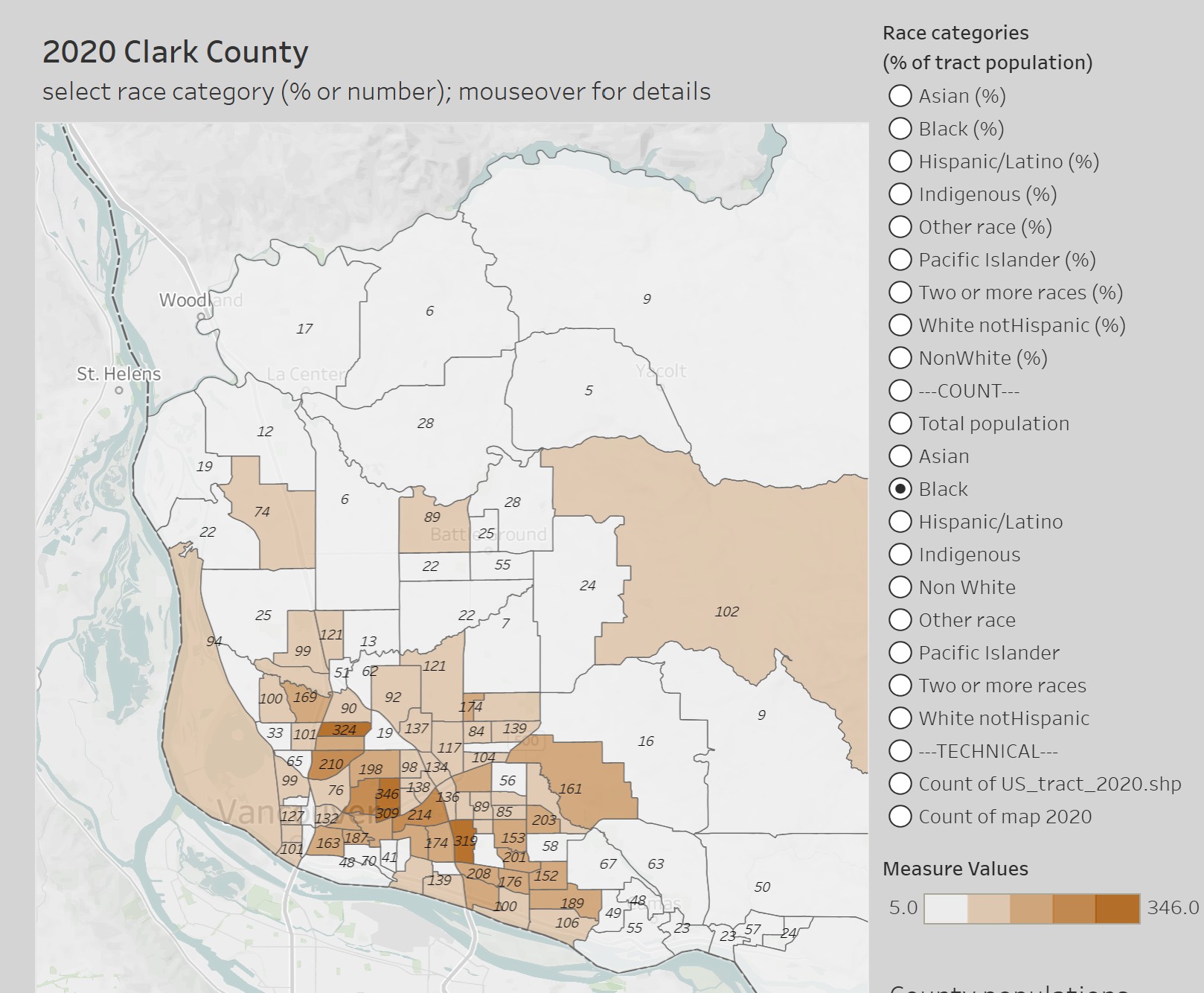

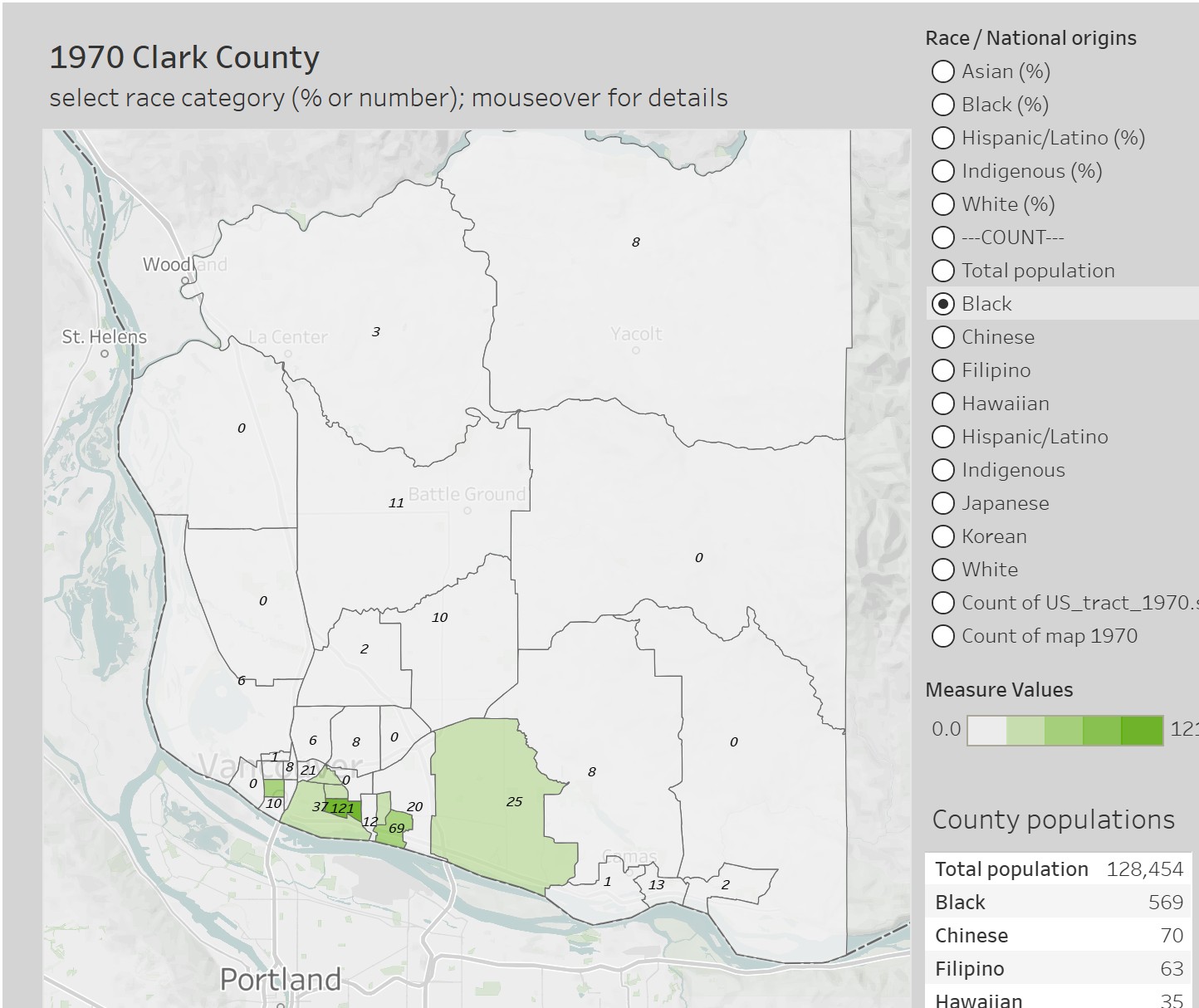

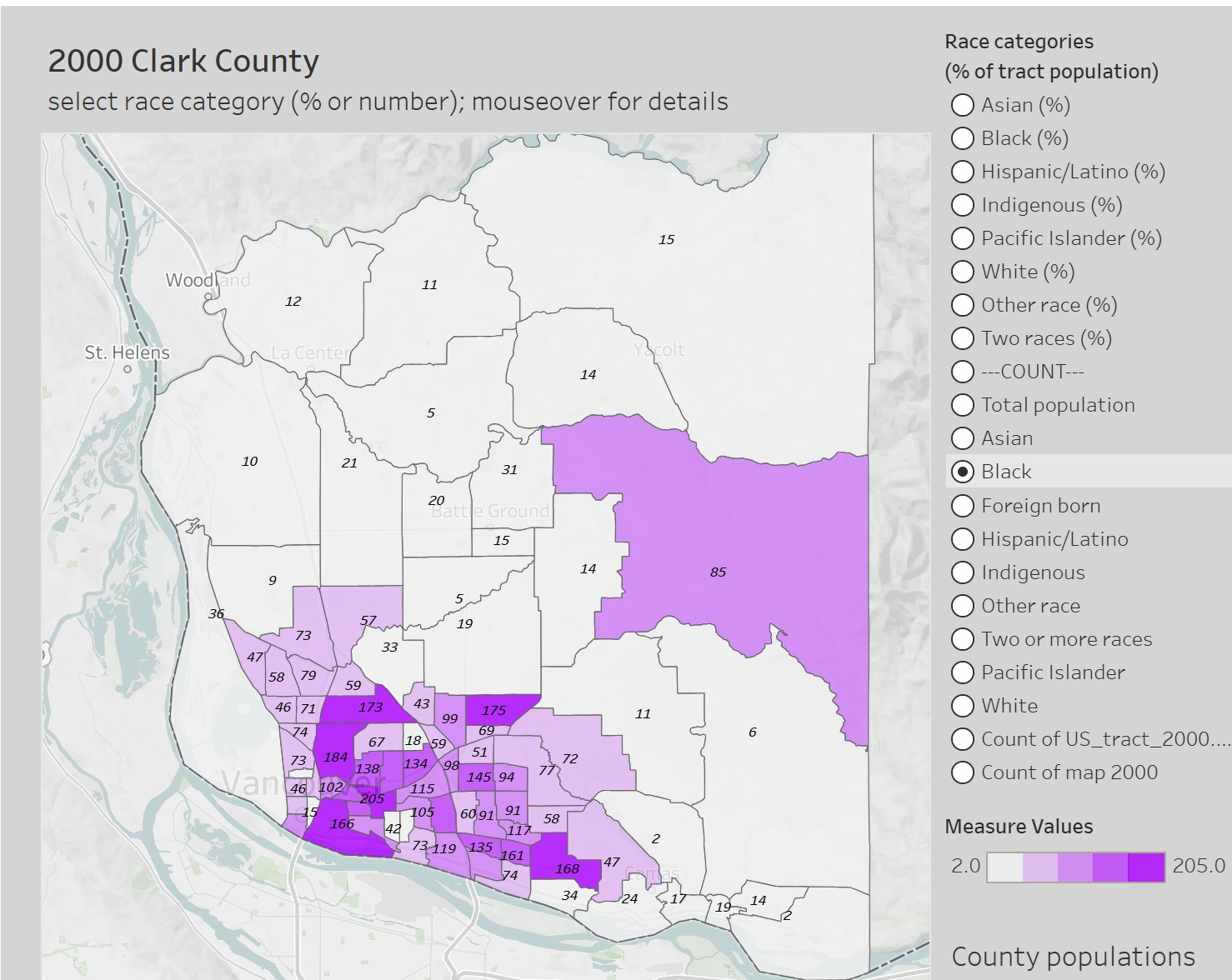

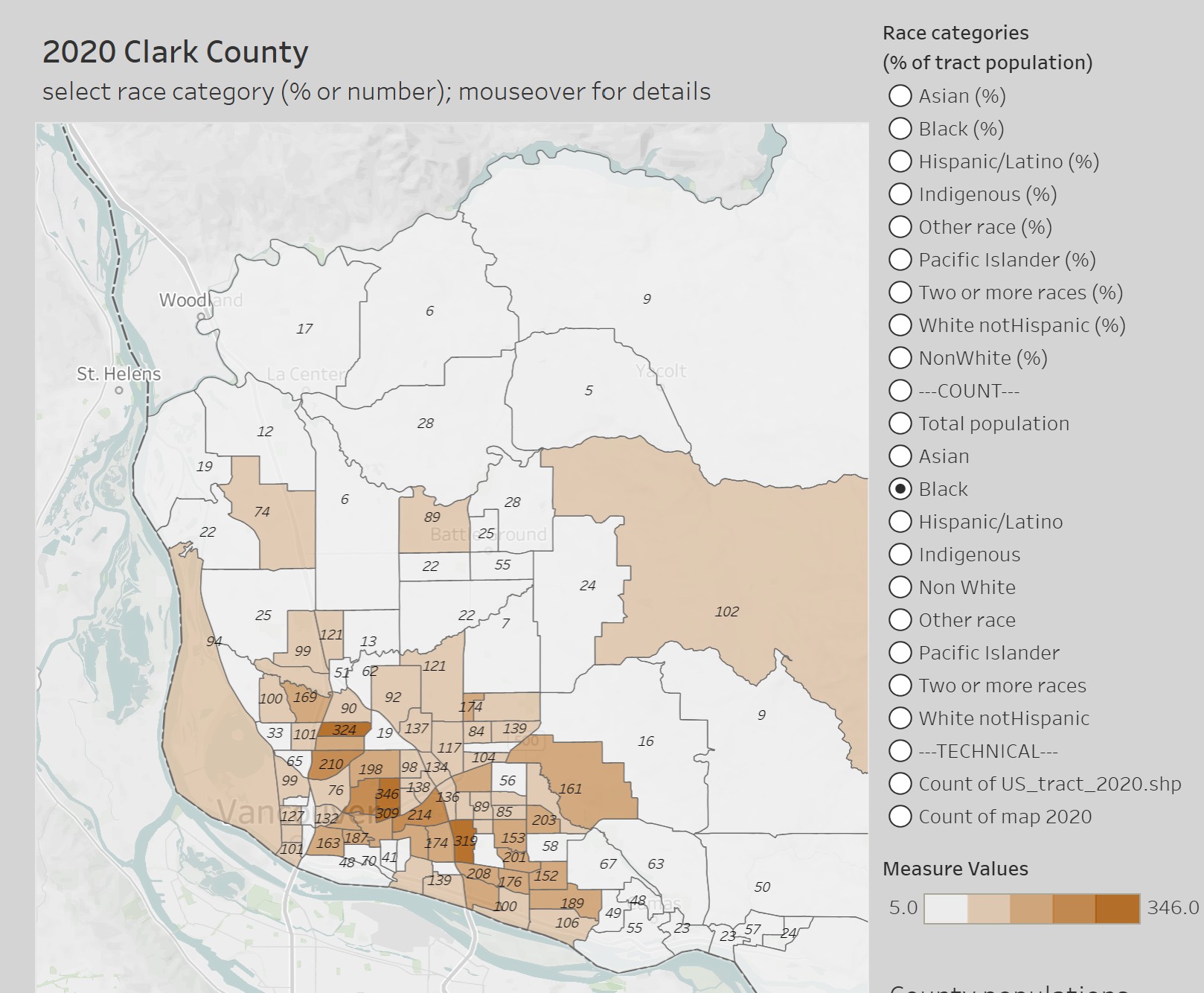

Click to visit interactive maps showing the residential patterns of different racial populations in Clark County from 1960 to 2020. These screenshots record the number of Black residents in each census tract.

Click to visit interactive maps showing the residential patterns of different racial populations in Clark County from 1960 to 2020. These screenshots record the number of Black residents in each census tract.

The civil rights organization quickly mobilized to contest the Vancouver Housing Authority’s plan to remove most of the wartime housing. In letters to local newspapers and appeals to the VHS and city authorities, Smith and others called for fairness and equal opportunities. The effort seems to have made a difference, Smith was appointed an advisor to the VHS and with that position and through broader lobbying efforts the NAACP probably slowed down the demobilization plans.[33]

The call for de-segregation (or “integration”) also registered and in later years VHS would claim credit for providing some openings for Black families in otherwise segregated public housing, while the city enjoyed headlines proclaiming “Vancouver Leads in Integration”. The article in the Oregon Journal barely justified the glowing headline, citing only a few examples of Black families able to buy or rent in previously segregated neighborhoods. Moreover, the new reputation hid the bigger truth. By the time that headline appeared in 1958, the city had lost all but 370 of its Black residents, a 95% decline.[34]

Slow openings

Population numbers tell a story of the slow reopening of Clark County in the last fifty years. In 1970, the county population was 99% White with only 569 African Americans, 398 Indigenous Americans, 371 Asian Americans, and 151 whose race was identified as “Other.” Starting in the 1980s the representation of people of color began to increase, reaching 4.5% in the 1990 census; 11% in 2000; 15% in 2010; and 27% in the 2020 census. In that year, the Black population reached 8,426, close to the World War II population peak. Indigenous folks numbered 3,624; Latinos 32,166; Asian-Pacific Islanders 20,212; and people claiming multiple racial identities 17,219.[35]

Bryce Penick is a Research Associate for the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project

Aerial photo of Kaiser shipyards lining the Columbia River during World War II. Vancouver's population doubled in size and for the first time included a substantial number of African Americans. (Courtesy National Park Service)

Aerial photo of Kaiser shipyards lining the Columbia River during World War II. Vancouver's population doubled in size and for the first time included a substantial number of African Americans. (Courtesy National Park Service) Fort Vancouver, 1845, sketch by Lt.Henry Warre (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries Digital Collection)

Fort Vancouver, 1845, sketch by Lt.Henry Warre (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries Digital Collection) Chiefs of the Kalispets, Flathead, Colville, and Coeur D’Alene nations after surrending at Fort Vancouver, 1856. Photo F. Aldrich. Washington State Historical Society.

Chiefs of the Kalispets, Flathead, Colville, and Coeur D’Alene nations after surrending at Fort Vancouver, 1856. Photo F. Aldrich. Washington State Historical Society._about_to_be_launched_on_5_April_1943_(NH_75634)-wiki.jpg) USS Casablanca, an escort carrier (baby flattop), about to be launched in Kaiser shipyard, 1943 (Wikipedia)

USS Casablanca, an escort carrier (baby flattop), about to be launched in Kaiser shipyard, 1943 (Wikipedia) New defense housing under construction in Vancouver (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

New defense housing under construction in Vancouver (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection) Walls come down in a house decommissioned by the Vancouver Housing Authority, 1957 (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

Walls come down in a house decommissioned by the Vancouver Housing Authority, 1957 (Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum, Washington State University Digital Collection)

Plat map showing the roads, blocks, and nearly 400 parcels of Evergreen Highlands, east of Vancouver overlooking the Columbia. All parcels were sold with the following restriction "Grantees agree that they will not sell, lease or in any way dispose of the above described property to any person or persons not a member of the Caucasian Race, or to any society or societies whose members are not members 6f the Caucasian Race."

.

Plat map showing the roads, blocks, and nearly 400 parcels of Evergreen Highlands, east of Vancouver overlooking the Columbia. All parcels were sold with the following restriction "Grantees agree that they will not sell, lease or in any way dispose of the above described property to any person or persons not a member of the Caucasian Race, or to any society or societies whose members are not members 6f the Caucasian Race."

.