The Alzheimer’s Association International Conference is the largest international meeting dedicated to advancing dementia science and clinical practice. Each year, AAIC convenes researchers, clinicians and dementia professionals from all career stages to share breaking research discoveries and clinical practice education that will lead to improvements in diagnosis, risk reduction and treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. This year, several big findings with relevance to brain health grabbed headlines. Here’s the down low on some of the preliminary research presented at the conference.

Red meat and brain health

One study showed that people who regularly eat processed red meat products, such as hot dogs, bacon, sausage, and bologne, have a greater risk of developing dementia later in life. The study followed more than 130,000 adults in the United States for up to 43 years to assess the association between red meat and dementia. During that period, 11,173 people developed dementia. Those who ate about two servings of processed red meat per week had a 14 percent greater risk of developing dementia compared to those who ate fewer than three servings per month. The study did not find a significant increase in dementia risk from eating unprocessed red meat, such as steak or hamburgers. The study found that the chance of getting dementia would fall by 20 percent if people replaced a daily serving of bacon or sausages with nuts, beans or tofu.

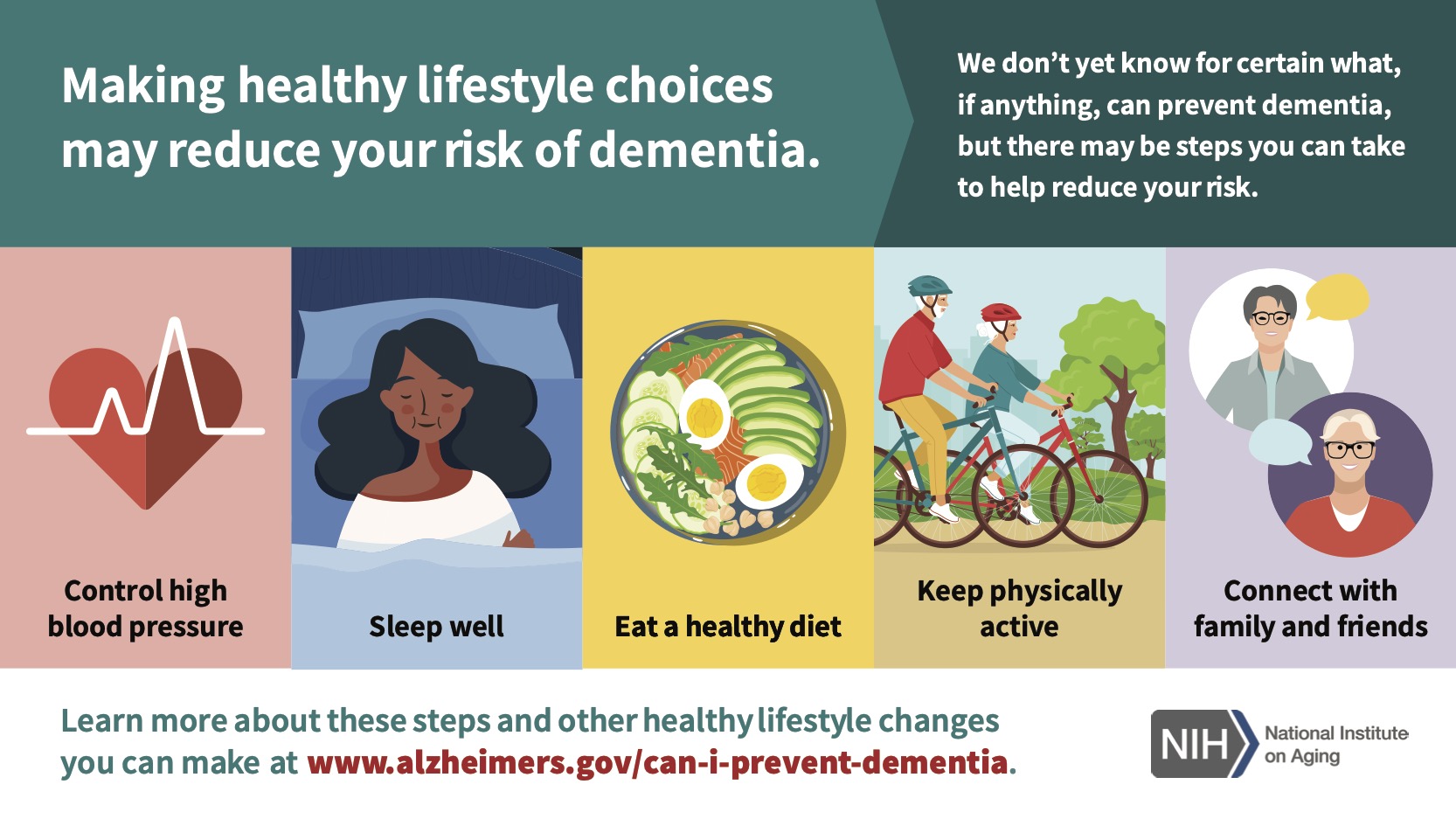

Modifiable dementia risk factors

The 2024 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care was presented at the AAIC. This report highlights recommendations for policy makers and individuals to help reduce dementia risk worldwide. It estimates that 7% of cases of dementia are attributable to high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) or “bad” cholesterol in midlife from around age 40 years, and 2% of cases are attributable to untreated vision loss in later life. Other risks, linked to 40% of all dementia cases, include lower levels of education, hearing impairment, high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, air pollution and social isolation. This report, as well as the two prior reports, is influenced by research at the University of Washington, particularly studies on the role of exercise and treatment of cataracts and hearing impairment in dementia prevention. UW ADRC’s Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, affiliate professor of medicine in the UW School of Medicine, has now worked on all three Lancet reports on dementia risk.

Promising Drug Treatments

At the AAIC, findings from a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled drug trial on liraglutide made a buzz. The drug is in a class of treatments known as GLP-1 Agonists, which are currently being used to help people manage diabetes, lose weight, and lower their risk of heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease. Among 204 people with mild Alzheimer’s dementia, those taking liraglutide lost 50 percent less brain volume overall in parts of the brain that affect memory, learning, language, and decision-making, compared to placebo. While these results are not definitive, drugmaker Novo Nordisk is currently conducting two large Phase 3 trials of the GLP-1 drug semaglutide, each with 1,840 participants, over the course of more than three years for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Results from these trials are expected by the end of 2025.

Blood tests for Alzheimer's diagnosis

Another study reported a blood test that was around 90% accurate in identifying Alzheimer’s in patients with cognitive symptoms seen in primary care and at specialized memory care clinics. Blood tests could mean simpler, more accessible, more accurate, and earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. Unlike a brain image or a spinal tap, a blood test would drastically reduce wait times for diagnosis and treatment. As newly approved treatments are indicated for people in the early symptomatic stages of the disease, using an easier way to detect early Alzheimer’s disease is important. While blood tests are ready to play a role in specialty care in specific circumstances, the issue of insurance coverage is not yet ironed out. As of now, there is no single test that can determine if a person is living with Alzheimer’s or another dementia. Physicians currently use diagnostic tools combined with medical history and other information including neurological exams, cognitive and functional assessments, as well as brain imaging, spinal fluid analysis, and blood tests, to make an accurate diagnosis.

Content adapted from the Alzheimer's Association