"Silent Sentinals" National Woman's party contingent from Pennsylvania picket White House 1917

(Library of Congress)

Introduction by Marina Hodgkin

On November 8, 2016, women all over the United States flocked to the polls to vote for Hillary Clinton in hopes she would become the first female president of the United States. After casting their ballots, most women continued with their usual routine. But hundreds of voters in Rochester, New York, went somewhere else: to Susan B. Anthony’s grave. By the end of the day, Anthony’s grave was plastered with “I Voted!” stickers. Visitors wanted to pay their respects and offer thanks to one of the women who made it possible for women to partake in American democracy.

Susan B. Anthony and her 19th century colleagues began the American suffrage movement with the simple yet firm belief that voting was a woman’s right. But it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century and the emergence of the second generation of suffragists that word of a national suffrage movement caught wind.[1]

In 1890 the two major suffrage organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Associate, merged to create the National American Woman Suffrage Associate (NAWSA). The movement unified the two different organizations behind one concrete cause: ensuring the vote for women.[2] With Wyoming already under their belts, they started on their journey of enfranchising women state-by-state. In 1893, Colorado became the second state to legalize women’s suffrage, followed by Idaho and Utah three years later[3]. The women were energized and hopeful after these victories, but it would be 14 years before another state would join the ranks of suffrage states.

Alice Paul, chair of the Congressional Union, 1915 (Library of Congress)

Alice Paul, chair of the Congressional Union, 1915 (Library of Congress)

During these years, Dora Lewis and other women of the organization grew tired of the slow state approach and began to urge for a national campaign. In 1910, as NAWSA grew stagnant under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt and Anna Howard Shaw, their wish became realized in the form of Alice Paul and Lucy Burns.[4]

Fresh off the heels of a life-changing stay in Europe where she was awakened to the suffrage movements in Britain, Paul returned to the U.S. and immediately joined the suffrage movement at home. NAWSA appointed her as chair of the Congressional Committee, a relatively minor part of the organization since their focus was still on the states. Paul recruited Lucy Burns, a friend she met while in Britain, and they set up shop at the all-but-abandoned committee office in Washington, D.C.[5] While NAWSA did not agree with the federal approach, they allowed Paul to operate and organize without getting in the way of the state-level campaign.

By the following year, Paul and Burns had formed the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), a subgroup to the committee. NAWSA hesitantly allowed Paul to organize a parade to publicize their demands to the incoming President and Congress. On March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, Paul and some 8,000 marchers paraded toward the White House.[6] Men gathered and filled the streets, making it nearly impossible for the parade to pass. The men jeered and harassed the women, even physically assaulting them, with little intervention from police. What had started as a pleasant procession nearly turned into a riot.

The unfortunate end to the event produced mass media attention, and soon people all over the country knew of the parade and the movement behind it. To Paul this was a good thing, but to the leaders of NAWSA it was irresponsible.[7] Fearing the loss of membership from women who believed the state-by-state approach was the only way to achieve the vote, NAWSA cut ties with Paul and the Congressional Union by the beginning of 1914.[8] This clash between suffragists, despite their shared goal, would go on to be a recurring theme in Paul’s career.

Suffragists demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, 1916 (Library of Congress)

Suffragists demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, 1916 (Library of Congress)

The Congressional Union, which focused on the support of disenfranchised women, began to work closely with the Woman’s Party of Western Voters, which supported enfranchised women. Together, they became the aggressive counterparts to the patient NAWSA. Drawing on her time spent in Britain with the radical Emmeline Parkhurst, her daughters, and their allies, Paul devised a method of militancy America hadn’t seen since Susan B. Anthony was arrested for illegally voting in 1872.[9]

Dedicated to holding the party in power responsible for women’s suffrage, Paul devised a plan with the CU to send two suffragists to every enfranchised state (which in 1914 totaled six, with the addition of Washington and California) to advise women to oppose any and all candidates from the Democratic Party.[10] Back in D.C., the women participated in aggressive congressional lobbying, questioning congressmen at work or in public about their support of women. The radical women were beginning to make a name for themselves.

The Congressional Union and Woman’s Party of Western Voters, no longer seeing the need to support enfranchised and disenfranchised women differently, merged to create the National Woman’s Party (NWP) in 1916. Their founding platform was to remain nonpartisan with the ultimate goal of a constitutional amendment ensuring suffrage for all women.[11]

July 14, 1917 pickets conduct an illegal wartime demonstration, expecting mob attacks and arrests (Library of Congress)

July 14, 1917 pickets conduct an illegal wartime demonstration, expecting mob attacks and arrests (Library of Congress)

After congressional lobbying failed to provide much progress, the NWP sent a few members to Wilson’s annual address to Congress. When the President’s address was underway, they silently stood and unfurled a banner they had snuck in underneath their coats that read, in giant letters, “Mr. President, what will you do for woman suffrage?” This marked the first act of nonviolent civil disobedience by the NWP.[12]

A little over a month later, on January 10, 1917, the NWP embarked on what would become a two-and-a-half-year long process that would ultimately end in a constitutional amendment providing voting rights for women.[13] They stood outside of the White House, equipped with banners aimed at the President and fierce determination. The right to petition was a sacred American tradition but political picketing, especially in front of the White House, was uncommon. Furthermore, political picketing by women was unheard of.[14] Wilson’s response was unsatisfactory, even condescending at times, never offering more than a smug smile or a tip of his hat as he came and went from the White House.

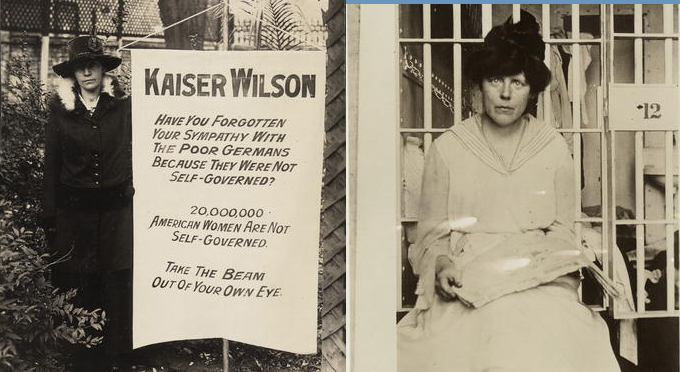

When the United States entered World War I, most of suffrage organizations, including NAWSA, backed down from their efforts in support for and solidarity with their country. But the NWP refused to back down, operating under the philosophy that democracy should begin at home.[15] They used picketing to highlight the contrast between nonviolent female protests and male war violence.[16] This was outrageous and infuriating to the public, who gathered in front of the picketers and harassed or assaulted them.

(left) Virginia Arnold holds Kaiser Wilson banner August 14 1917 before mob attacks.

(left) Virginia Arnold holds Kaiser Wilson banner August 14 1917 before mob attacks.

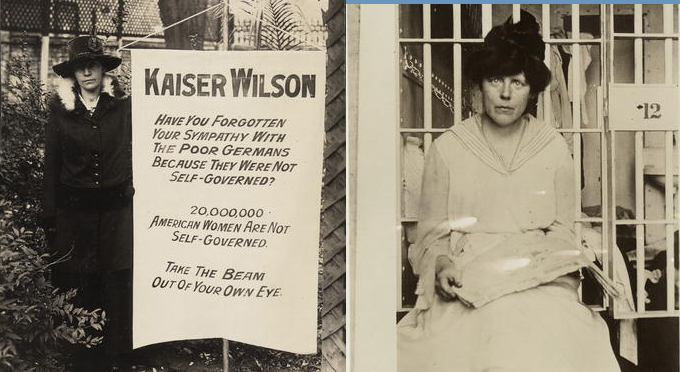

(right) Lucy Burns led hunger strikers and suffered severe injuries during force feeding.

(Library of Congress)

And still the women remained. Paul learned to use negative opinions to her advantage and welcomed the media frenzy that soon rained down upon the picketers. The mass reporting only served to widen the NWP’s audience, turning more women onto the cause.

Publicity, good or bad, proved to be a key ingredient for the success of the suffrage movement. In June 1917, after six months of persistent picketing, Lucy Burns and Katherine Morey set out in front of the White House with a banner that read, “We, the women of America, tell you that America is not a democracy,” and the two were arrested and charged with obstructing traffic.[17] Upon their release, they returned to the picket lines. The pickets continued and so did the arrests. As summer turned into fall, the pickets began getting longer and harsher sentences: up to 60 days at Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia.[18] The conditions of the workhouse were horrendous, and Paul informed the press of the spoiled, worm-infested food, physical abuses and refusal to designate the women as political prisoners. Then, as the leader of the movement, Paul decided to do something drastic.

In October 1917, Paul carried a banner to the White House with President Wilson’s own words: “The time has come to conquer or submit. For us there can be no other choice.” She was arrested and sentenced to seven months in jail.[19] When Paul initiated a hunger strike to protest the jail conditions, the jail responded with forced feedings and the press instituted a deathwatch on Paul. This act by the media was the final straw for the President, who moved for all suffragists to be released in late November.[20] The NWP remained quiet for the rest of the year as their members healed and replenished their energy.

In January 1918, President Wilson formally endorsed the amendment for women’s suffrage. It passed the House of Representatives but was denied by the Senate, so the women returned to the picket lines.[21] They spent the year aiming their banners at the Senate, pushing for amendment approval. By the beginning of 1919, they had begun what are now known as the “watchfires for freedom” outside of the White House, burning the words of President Wilson to highlight the hypocrisy of his administration. On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives passed the 19th Amendment. On June 4, it passed the Senate. This marked the end of the picketing but did not mark victory yet.[22]

For the remainder of 1919 and through the summer of 1920, the NWP lobbied states to secure ratification. On August 18, Tennessee became the 36th and last state needed to ratify the amendment, and eight days later, Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed the amendment into law. This granted that a citizen’s right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” [23]

[1] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[5] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[9] Ford, Linda. Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited. (Edited by Jean H. Baker. Oxford: Oxford University Press), 2002.

[11] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[13] Zahniser, J.D. “’How long must we wait?’” American History 50, no. 5 (December 2015): 51-59.

[15] Ford. Votes For Women.

[17] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[18] Zahniser. “’How long must we wait?’”

[19] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[20] Zahniser. “’How long must we wait?’”

[21] Ford. Votes For Women.

[23] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

Alice Paul, chair of the Congressional Union, 1915 (Library of Congress)

Alice Paul, chair of the Congressional Union, 1915 (Library of Congress) Suffragists demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, 1916 (Library of Congress)

Suffragists demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, 1916 (Library of Congress) July 14, 1917 pickets conduct an illegal wartime demonstration, expecting mob attacks and arrests (Library of Congress)

July 14, 1917 pickets conduct an illegal wartime demonstration, expecting mob attacks and arrests (Library of Congress) (left) Virginia Arnold holds Kaiser Wilson banner August 14 1917 before mob attacks.

(left) Virginia Arnold holds Kaiser Wilson banner August 14 1917 before mob attacks.