|

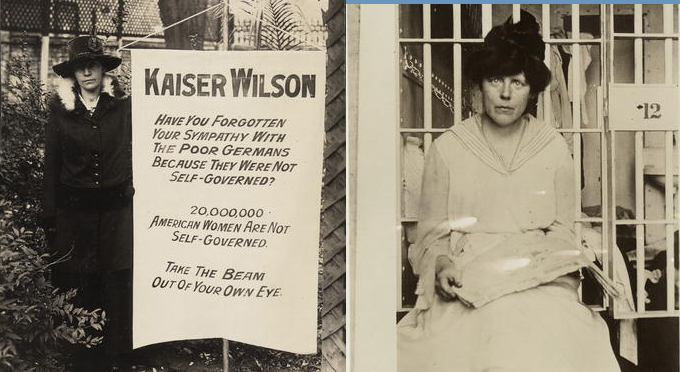

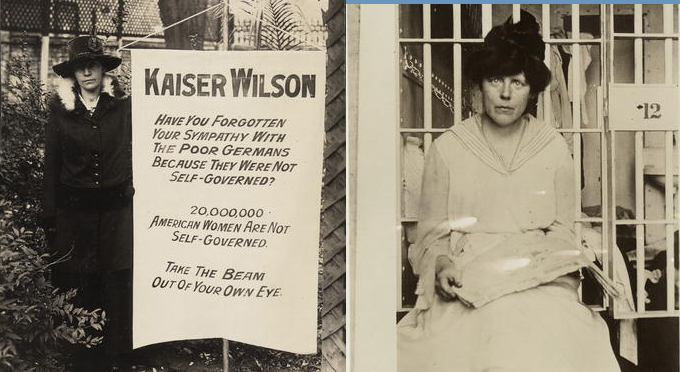

Virginia Arnold holding Kaiser Wilson banner August 14 1917 before mob attacks (left)

Lucy Burns led hunger strikers in the Occoquan Workhouse and suffered severe injuries during force feeding.

(Library of Congress)

1917 War at Home (by Samantha Mayes)

Before 1917, the NWP’s chief methods were lobbying and petitioning. The women continuously put pressure on officeholders and even complied a congressional card index with information about every member of the House and Senate. This allowed pro-suffrage lobbyists to make their arguments uniquely persuasive for each lawmaker. Unfortunately, this technique did not make as big of an impact as planned. Realizing that they needed a stronger approach, the NWP then switched to more confrontational demonstrations that led to arrests and imprisonment.

While other groups, such as NAWSA, softened their tone as the United States entered World War I in 1917, the NWP remained a strong, one-issue party.[1] The National Woman’s Party stood essentially alone in fighting for suffrage as World War I began, continuing to petition President Wilson and other government officials, going to jail to fight for suffrage, and keeping suffrage in the daily news. The NWP had always seemed radical to the average American, but suffrage no longer was.

The first suffrage picket line leaving the National Woman's Party headquarters to march to the White House gates on January 10, 1917 The first suffrage picket line leaving the National Woman's Party headquarters to march to the White House gates on January 10, 1917

1917 began with an unanswered petition to President Wilson at the White House.[2] Frustrated with the President’s unwillingness to help, members of the NWP picketed outside the White House during the following week.[3] This was shocking to the public; many viewed picketing as a disrespectful form of political speech, especially from women. However, many others were sympathetic to the NWP and gathered in large crowds to watch their protest. The pickets continued for a few months and drew crowds on days like Teacher’s Day, Voter’s Day, and College Day.[4] [5] Overall, the crowd’s reaction was positive, and the White House guards and the President behaved politely toward the protesters.

New York Pickets at the White House, January 26, 1917 New York Pickets at the White House, January 26, 1917

The tone changed in the summer of 1917 as war fever mounted and Congress passed a tough Espionage Act that made it a federal crime to interfere with the war effort. Undeterred, NWP women began displaying banners with messages criticizing President Wilson. They held even larger demonstrations during visits from foreign dignitaries, which many viewed as unpatriotic. Disagreements between NAWSA and the NWP continued throughout the picketing, and NAWSA president Mrs. Catt sent a letter to Alice Paul expressing her disapproval of their tactics and fear that the NWP’s actions would impede victory for suffragists. Representative Harrison had also announced that he would refuse to vote on the suffrage amendment if the picketing at the White House continued. But these threats did not deter the NWP; the pickets had “’no access to weapons’ except for the potent weapon of their own ‘moral’ action: public displays of female, defiant, resistant strength.”[6]

Section of Working Women's Picket --Feb. 17, 1917 Section of Working Women's Picket --Feb. 17, 1917

In June of 1917, the party decided to add another element to their picketing, which led to a change in attitude by law enforcement and spectators. On June 20, the pickets held a sign that accused that president of lying to Russia when he called the U.S. a democracy; the NWP’s definition of democracy included equal rights for women and men. Many spectators viewed this claim as disrespectful and aggressive. A Washington Post article described the scene as a frenzy of anger: spectators formed mobs, tore the posters out of the picketers’ hands, ripped them to shreds (“Flaunt Fresh Banner”). The women returned with a duplicate of the banner the following day.

On June 22, 1917, Lucy Burns and Katharine Morey – who had held the Russian banner the previous day – became the first two pickets to be arrested. The police claimed they were arrested for obstructing traffic and released them without charges. More pickets were arrested in the following days, and most of them served three days in jail rather than paying fines. Picketing continued, even as jail sentences became longer and longer and crowds became more violent. Suffragist Inez Haunes Irwin described a scene in which young boys spat at them and called them names and said that “sometimes the crowds would edge nearer and nearer until there was but a foot of smothering, terror-fraught space between them and the pickets."

Meanwhile hostility mounted. The NWP demonstrations were denounced as "treasonous" by key politicans and some newspapers. The Woman's Party was also losing members, some who turned away because they felt that their primary loyalty belonged to the nation in time of war, others out of a sense of caution.

Bastille Day. Julia Hurlbut of N.J. leading. Iris Calderhead of Kansas at right waiting for mobs to attack pickets so she can order out new banners.1917. Bastille Day. Julia Hurlbut of N.J. leading. Iris Calderhead of Kansas at right waiting for mobs to attack pickets so she can order out new banners.1917.

On July 14, which France celebrates as "Bastille Day," sixteen women were arrested before they could take up their picket station at the White House. They were sentenced to 60 days imprisonment for "obstructing traffic" and sent to Occuquan Workhouse, a federal prison in northern Virginia. After three days, they were pardoned by President Wilson and released. But his patience had now ended.

On August 14, Elizabeth Stuyvesant and other picketers left headquarters with a new set of banners, one of which called the President, "Kaiser Wilson." The women were quickly attacked and in the scuffle Stuyvesant's clothes were torn and their banners siezed. The crowd chased them back to headquarters and tore signs and banners off the building. A pistol shot broke a window and nearly hit women working inside. More violence and arrests followed in the next month whenever activists appeared on the streets. And the prison sentences became more serious, 60 days with no early release, then six month and seven month terms.[8]

1917 Hunger Strikes (by Hannah Dinielli and Paige Peacock)

, and Madeleine Watson of Chicago aug1917.jpg) Arrest of White House pickets Catherine Flanagan of Hartford, Connecticut (left), and Madeleine Watson of Chicago August 1917 Arrest of White House pickets Catherine Flanagan of Hartford, Connecticut (left), and Madeleine Watson of Chicago August 1917

Imprisonment offered new opportunities for resistance and for the kind of publicity that NWP strategists knew was needed to keep the campaign underway. Here the tactics of the British suffrage movement provided a model.

First, with each round off arrests, supporters from around the country flooded the White House with telegrams denouncing the attacks on peaceful protest and demanding that the release of prisoners, with the New York Times dubbing this a “telegraphic campaign of protest.”[10]

Secondly, the women demanded that they be recognized as political prisoners and organized passive resistance where they refused to do their assigned workhouse tasks which included sewing and other kinds of labor, insisting they would resist until their political status was acknowledged.

Sailors attacking pickets while policemen look casually on, summer 1917 (Library of Congress) Sailors attacking pickets while policemen look casually on, summer 1917 (Library of Congress)

Third, some refused to eat, resurrecting the hunger strike tactic that Alice Paul and Lucy Burns had employed years before in London. The hunger strikes resulted in force feedings that were one of the key tools used to gain attention and support for the NWP. In her book Iron-Jawed Angels, Linda G Ford explains that “to suffer for a cause is very impressive, proving sincerity… The suffering of the suffragist prisoners proved a powerful technique for the militants in converting ‘onlookers’.” [11]

Alice Paul was arrested on October 20, 1917, and sentenced to seven months in jail.[12] She quickly began a hunger strike, refusing all food. After three days, prison guards strapped her down and inserted a feeding tube. In total, 16 suffragists decided to participate in hunger strikes while behind bars, and all were eventually subject to force feeding. Additionally, “the doctors and matrons ‘tried to persuade, bully and threaten’ the suffragists out of ‘sticking to their purpose,’ the hunger strike.”[13]

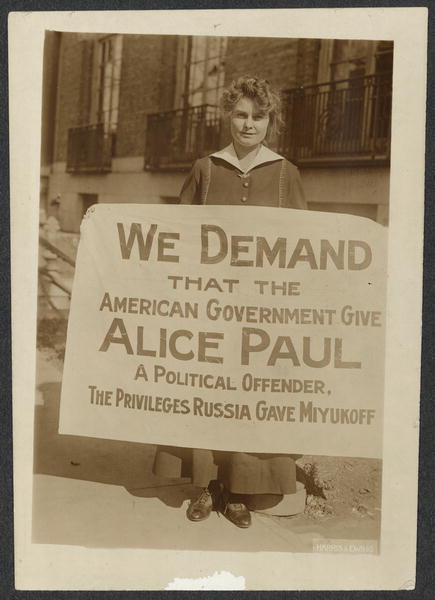

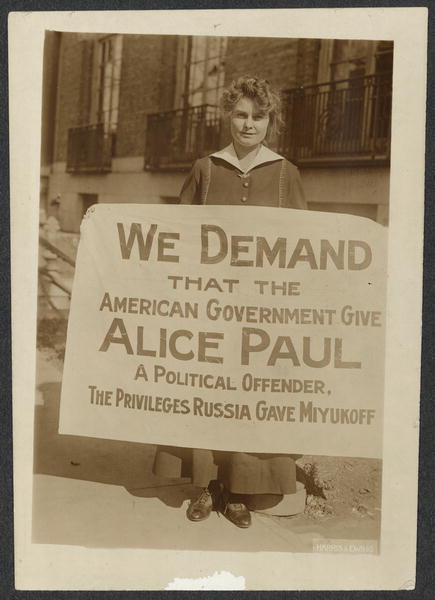

Lucy Branham demands justice for imprisoned Alice Paul, late 1917 Lucy Branham demands justice for imprisoned Alice Paul, late 1917

The government denied that the women suffered abuse. In an article from November 9th 1917 in the Washington Evening Star, the chief visiting physician of the jail attempts to dismiss the claims of force feedings in the jail. He claimed that, “tube feeding is by no means necessarily forcible feeding, and is not so in the present cases.” He even goes on to claim that “the patients are not nervous; on the contrary they are more calm than usual… Both are lying in bed for the sake of rest” and that Alice Paul “is very pleasant, moreover, about it all.” [14]

Suffragists countered with details about Paul's resistance and the pain of force-feeding. Rose Winslow wrote in her prison diary that "Miss Paul vomits much. I do, too . . . . We think of the coming feeding all day. It is horrible." She continued, "I had a nervous time of it, gasping a long time afterward, and my stomach rejecting during the process. I spent a bad, restless night, but otherwise I am all right. The poor soul who fed me got liberally besprinkled during the process. I heard myself making the most hideous sounds.... One feels so forsaken when one lies prone and people shove a pipe down one’s stomach." The women also complained of other violence. As Cora Week recalled, “As I was sitting in a chair quietly reading a paper two rough guards rushed into the room from the dark night outside, fell upon me from the rear, seized my arms, bending them sharply backwards, dragging me backward over the chair tops and suitcases and so out into the darkness.” [9]

Abby Scott Baker in prison dress, 1917. Baker was head of the NWP's lobbyist team (Library of Congress) Abby Scott Baker in prison dress, 1917. Baker was head of the NWP's lobbyist team (Library of Congress)

The violent methods used to punish passive resistance and force feedings provided the shock factor needed to persuade others to support their cause as well as acknowledge the injustices being done to these women. The torturous experience of force-feeding included incidents of cruel methods such as when Lucy Burns was force fed with the tube being forced up her nose, which proceeded with bleeding and injury. What these women endured provided the "shock factor" they needed to win the attention and sympathy of many Americans, including in time, President Wilson.

Meanwhile other NWP activists were organizing that shock factor. The Woman's Party chartered a special train, dubbed the "Prison Special." Newly released inmates, wearing prison uniforms, traveled from city to city, holding rallies, speaking about the abuse they suffered in Occoquan as well as about the cause. The press coverage, telegrams, and letters weighed on Wilson. First, he ordered an investigation, then in December he order that Paul, Burns, and the remaining prisoners be released.[15]

As soon as Alice Paul and her fellow NWP members were released from prison, they shared their horror stories. The harsh prison conditions earned them public sympathy for the suffrage movement – thousands gathered to hear their stories when they went on a speaking tour dressed in prison attire – and increased pressure on President Wilson to act.Their dogged attempts finally led to success in 1918, when President Wilson announced his support for national woman suffrage.

1918 “Women Sure to Win the Vote” (by McKenna Donahue)

Dora Lewis of Philadelphia on release from jail after five days of hunger striking. Aug 1918 Dora Lewis of Philadelphia on release from jail after five days of hunger striking. Aug 1918

For suffragists, “there was some disagreement on exactly what degree of combativeness… was necessary for true militancy, but all agreed that it involved defiance of and resistance to authority.”[16]The NWP reached their “peak stage of militancy” in 1918.[17]

Though the U.S. was in the thick of World War I, the NWP was full of hope at the start of 1918. A January 2 headline in The Washington Post read, “Women Sure of Vote.”[18] With Congress reconvening on January 3 to vote on the Susan B. Anthony amendment, the suffragists were reportedly “taking stock,” and found that “on the Republican side of the House more than the necessary two-thirds is pledged.”[19] But the members of the NWP did not sit back and wait; The Washington Post reported “threats of the woman’s party to resume militant tactics if the Federal constitutional suffrage amendment is not passed.”[20] The Washington Post wrote on January 9, 1918, that “woman suffragists declared last night that they are about to win their first congressional victory for the Federal constitutional amendment.”[21] House Committee Chairman Raker was just as sure as the NWP, expressing “his entire confidence that the woman suffrage resolution will pass the House by a vote equal, if not exceeding, that by which prohibition was adopted.”[22]

Wearing prison uniforms Doris Stevens, Alison Turnbull Hopkins, Eunice Dana Brannan speak during "prison special" tour 1919. An earlier "prison special" tour had attracted massive publicity in 1918 Wearing prison uniforms Doris Stevens, Alison Turnbull Hopkins, Eunice Dana Brannan speak during "prison special" tour 1919. An earlier "prison special" tour had attracted massive publicity in 1918

The night before the vote, President Wilson finally made a statement in support of the amendment; on the night before the vote in the House, “twelve Democratic members called at the White House with word that many of their colleagues wanted advice from the head of their party as to the position they should take.”[23] Wilson encouraged House Democrats “to vote for the amendment as an act of right and justice to the women of the country and of the world.”[24] The resolution passed in the House the following day “with exactly the required number of affirmative votes,” 274 to 136. [25] Moving forward, wrote The Washington Post, “suffragists hope to bring the Senate into line so as to have the amendment before State legislatures during the coming year.”[26]

Another interesting aspect of the NWP was their tie to global politics, especially socialism. Following the House victory, the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS), “made public…an open letter of apology to Miss Alice Paul, the Woman’s party and to Socialists for accusing them of circulating misleading reports as to the President’s attitude on the question.”[27] In a February 1918 speech, Beulah Amidon of the NWP said, “Socialism helps woman suffrage everywhere.”[28] She added that France, Italy, Russia, England, and Hungary had all made steps toward granting women the right to vote, and socialism “in all the nations of Europe… has aided in the international movement for woman suffrage.”[29] Amidon also linked wartime solidarity and the passage of the suffrage amendment, “since practically all of this nation’s allies and one of her enemies have agreed to permit women to participate in their national politics.”[30] Even President Wilson told Chairman Raker “his reason for favoring the Federal suffrage amendment was to place the United States in complete harmony with its allies…We cannot afford to lag behind, to take a reactionary position, on this matter.”[31]

With a win in the House under their belt, the NWP focused their attention on lobbying in the Senate. According to The Washington Post, “Republican support of the amendment is fully… as great in the Senate as in the House,”[32] while the Democrats “avoided responsibility for defeat by a 50 percent vote.”[33] The NWP continued to make headlines during this time. In March 1918, the D.C. Court of Appeals declared “picketing of the White House by militant suffragist members of the National Woman’s Party” that had occurred in 1917 and resulted in several arrests “was not in itself unlawful.”[34]According to the New York Times, the NWP issued a statement declaring “suits for damages aggregating $400,000, brought by eight of the women who were imprisoned for picketing, would be pressed for trial.”[35] Though the NWP urged President Wilson “to give further support to the Federal Woman Suffrage amendment,”[36] Secretary Tumulty informed them that there was nothing more Wilson could do for them, and nothing more they could say to him to increase his interest in the matter.[37]

Suffrage protestors burn speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. September 16,1918 Suffrage protestors burn speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. September 16,1918

The lobbying, press coverage, pledged commitments, and political victories made the NWP once again confident before the Senate vote. According to The Washington Post, Paul declared that the amendment “can easily pass, even if antis are appointed.”[38] Unfortunately, on June 28, “Senators opposed to the Susan B. Anthony resolution launched a determined filibuster.”[39] The delay was partially due to difficulty in finding a pair for Senator Ollie James, an anti-suffragist who was ill. The filibuster held up bills for $20 billion in vital war supplies, so the suffragists stepped aside. However, Senator Jones assured he would “renew [the resolution] immediately upon the disposition of the big supply bills.”[40]

After this heartbreaking turn of events, the NWP appealed to President Wilson, asking him to “prevent a Senate recess until the suffrage amendment has been passed.”[41] They once again recalled the war effort, declaring that “war for democracy is a mockery if simple justice is denied to American women… Let the Senate proclaim liberty at home before July the Fourth is celebrated across the sea.”[42]

The NWP accelerated their radical, militant tactics, in a campaign ultimately “met with anti-female rhetoric, violence and no Senate action.”[43] In July 1918, NWP members “provoked excitement as the final session of the Republican Convention was drawing to a close”[44] with a banner flung from the gallery claiming Senator Wadsworth obstructed the freedom of women: “We demand support for the national suffrage amendment or his resignation from the Senate.”[45] Three men tried to tear the banner down, but “the twelve women stood their ground and hung onto it.”[46] The men were “on the point of being bested by the seasoned pickets when Miss Anne E. Peck… joined the mêlée and handled the women with less gentleness than the men had displayed.”[47] This row caused much shouting and disturbance, and Mrs. Wadsworth even made an appearance, attempting to defend her husband and shaking hands with the NWP members.

Police arresting party demonstrators outside Senate Office Building, Oct. 1918. Police arresting party demonstrators outside Senate Office Building, Oct. 1918.

At the end of the month, The Washington Post reported that White House picketing would begin again on Saturday, August 3.[48] But this demonstration would “not be made on the White House mall, but in Lafayette Square… and will take the form of a mass meeting” in opposition to the Senate.[49] This demonstration resulted in the arrest of 48 women, who were charged with congregating in a park without a permit. According to the New York Times, despite the fact that Alice Paul was “on the side walk and not taking part in the demonstration… one of the policemen said: ‘There’s the leader; get her.’”[50] The Washington Post reported that a Mrs. Lawrence of Philadelphia declared, “My friends… I wish to tell you why this meeting was called and is being held. America stands for democracy –”[51]The reporter added, “As the word ‘democracy’ yet hung on her lips, two policemen grasped her by either arm.”[52]

Police arresting party picketers outside White House, August 1918 Police arresting party picketers outside White House, August 1918

The Washington Post wrote the following day that “forty-eight… suffragists were denied the privilege of spending the week-end in jail when Judge McMahon… refused the plea of the members of the National Woman’s Party who were arrested… that their collateral be withdrawn.”[53] Alice Paul expressed her frustration that their case had been delayed, which forced them to stay away from their homes and war work for a full week, “all because the police had taken the law into their own hands and exceeded their authority,” for “no permits are required in public parks.”[54] The arrests increased the ardor of the suffragists, and more demonstrations were planned. The suffragists’ militant strategies were condemned by many Senators, who claimed that the demonstrations were “uncalled for and hurtful to the cause… the women were only seeking notoriety.”[55] Senator Thomas said, “If this propaganda continues… it may cause some of us to reconsider our attitude on the amendment.”[56]

The suffragists were ultimately sentenced to 10 days in jail, 17 of them receiving an additional five for climbing on a statue of General Lafayette. The women “made no attempt to appeal from the decision… the women refused to answer any questions… and remained silent.”[57] While in jail, they engaged in a hunger strike, which resulted many of the women becoming critically ill and the jail authorities considering forcible feeding.[58] This marked a turning point in the NWP’s campaign for suffrage: “Paul’s militants developed new strategies based on using the leverage of women’s political power as voters… then as women petitioners and pickets, and then as public martyrs.”[59]

In mid-September, when the Senate was believed to finally vote, the suffragists “confident that the Anthony amendment will be passed.”[60] A significant amount of Senators were absent and unpaired, which delayed the vote until early October.[61] The result was a major disappointment: after five days of bitter debate, the amendment “received on the final roll call two votes less than the necessary two-thirds majority,” with 54 for, 30 against, and 12 absent, all paired.[62] President Wilson’s personal appeals and letters to Senators apparently did not change a single vote. Despite the loss, Chairman Jones was sure the defeat was only temporary and that the contest would be renewed after the November elections, “when changes in leadership are certain.”[63]

1918 ended on yet another hopeful note, with party members lighting “watchfires of freedom”[64] on the sidewalk in front of the White House starting New Year’s afternoon of 1919. The fires would be kept burning “with the speeches on liberty and freedom delivered since that day by President Wilson in Europe” and a bell would ring every two hours at NWP headquarters.[65] This put a spotlight on President Wilson: “In the final campaign, Paul and her forces concentrated… on the President himself, dogging his every step, burning him in effigy”[66] until they finally won victory in the Senate and the states in 1920.

[1] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986, p. 113.

[2] “Memorial Petitions Presented to the President.” The Suffragist. January 17,1917. Page 4-6.

[3] “Suffragist Waits at the White House for Action.” The Suffragist. January 17,1917. Page 7-8.

[4] “State Delegation Joins the Picket Line at the White House.” The Suffragist. January 31,1917. Page 4-6.

[5] “Silent Watch at the White House Continues.” The Suffragist. February 17, 1917. Page 4-5.

[6] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1991. Print. p. 124

[7] “Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman's Party Suffrage Campaign." Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman's Party Suffrage Campaign (n.d.): n. pag. American Memory. The Library of Congress. Web.

[8] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1991. Print. p.

[9]Winslow, Rose. "Starving for Women's Suffrage: "I Am Not Strong after These Weeks" History Matters, n.d. Web. 04 http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5336/%20

[10] “SUFFRAGISTS WIRE WILSON: Start a Telegraphic Campaign of Protest Against Sentences.” New York Times. 19 July 1917: 2; “Pardoned Women’s Counsel Push Anthony Amendment.” The Washington Post. 20 July 1917: 1.

[11] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1991. Print. p.;

[12] “Seven Month Sentence for National Suffrage Leader.” The Suffragist. October 27, 1917. Page 4.

[13] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1991. Print. P. 182

[14] "Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, November 09, 1917, Page 2, Image 2." Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress, n.d. Web. 04 Feb. 2016; Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman's Party Suffrage Campaign (n.d.): n. pag. American Memory. The Library of Congress. Web.

[15] “Government Forced to Release Suffrage Prisoners From Occoquan.” The Suffragist. November 28,1917. Page 4-5.

[16] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1991. Print. p. 7

[17] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920. Lanham, MD: U of America, 1991. Print. p. 225

[18] "WOMEN SURE OF VOTE." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 2, 1918, p. 4.

[20] "CLASH ON SUFFRAGE BEFORE COMMITTEE." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 6, 1918, p. 6.

[21] "SEE SUFFRAGE VICTORY." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 9, 1918, p. 2.

[23] "GIVE VOTE TO WOMEN IS ADVICE BY WILSON." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 10, 1918, p. 1.

[25] "WOMAN SUFFRAGE WINS IN HOUSE BY ONE VOTE." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 11, 1918, p. 1.

[27] "ANTI-SUFFRAGISTS AIM SLAP AT WILSON." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Jan 28, 1918, p. 1.

[28] "Socialism Helps Woman Suffrage Everywhere, Says Beulah Amidon." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Feb 18, 1918, p. 9.

[31] Special to The New York Times. "SUFFRAGISTS QUOTE WILSON'S SUPPORT." New York Times (1857-1922), Feb 25, 1918, p. 18.

[32] "'LOBBY' HARD FOR VOTES." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 28, 1918, p. 5.

[34] Special to The New York Times. "SUFFRAGE PICKETS WIN ON APPEAL." New York Times (1857-1922), Mar 05, 1918, p. 1.

[36] "ANSWERS SUFFRAGE PLEA." New York Times (1857-1922), May 25, 1918, p. 8.

[38] "WOMEN LOOK TO TWO STATES."

[39] "DEFEAT SUFFRAGE VOTE.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jun 28, 1918, p. 1.

[41] "ASK WILSON TO STAY RECESS." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 05, 1918, p. 9.

[43] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991), p. 225

[44] Special to The New York Times. "MILITANTS CAUSE ROW IN CONVENTION HALL." New York Times (1857-1922), Jul 20, 1918, p. 6.

[48] "PICKETING AGAIN TO BEGIN SATURDAY." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul 31, 1918, p. 3.

[50] Special to The New York Times. "SUFFRAGISTS AGAIN ATTACK PRESIDENT." New York Times (1857-1922), Aug 07, 1918, p. 1.

[51] "TAKE 48 SUFFRAGISTS." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Aug 07, 1918, p. 3.

[53] "NO CELLS FOR "SUFFS"." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Aug 08, 1918, p. 12.

[55] "DEMONSTRATION BY WOMEN DENOUNCED." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Aug 09, 1918, p. 1.

[57] "SUFFRAGISTS GIVEN TEN DAYS IN JAIL." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Aug 16, 1918, p. 1.

[58] ""HUNGER" STRIKES MAKE "SUFFS" ILL." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Aug 20, 1918, p. 12.

[59] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991), p.. 5

[60] “SENATE TURNS TO SUFFRAGE.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Sep 20, 1918, p. 3.

[61] "SUFFRAGE LACKS VOTE." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Sep 27, 1918, p. 2.

[62] "SENATE DENIES VOTE TO WOMAN." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Oct 02, 1918, p. 1.

[64] "SUFFRAGISTS TO FIRE ALTAR IN WASHINGTON." Los Angeles Times (1886-1922), Dec 31, 1918, p. 1.

[66] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991), p. 225

|

The first suffrage picket line leaving the National Woman's Party headquarters to march to the White House gates on January 10, 1917

The first suffrage picket line leaving the National Woman's Party headquarters to march to the White House gates on January 10, 1917 New York Pickets at the White House, January 26, 1917

New York Pickets at the White House, January 26, 1917 Section of Working Women's Picket --Feb. 17, 1917

Section of Working Women's Picket --Feb. 17, 1917 Bastille Day. Julia Hurlbut of N.J. leading. Iris Calderhead of Kansas at right waiting for mobs to attack pickets so she can order out new banners.1917.

Bastille Day. Julia Hurlbut of N.J. leading. Iris Calderhead of Kansas at right waiting for mobs to attack pickets so she can order out new banners.1917., and Madeleine Watson of Chicago aug1917.jpg) Arrest of White House pickets Catherine Flanagan of Hartford, Connecticut (left), and Madeleine Watson of Chicago August 1917

Arrest of White House pickets Catherine Flanagan of Hartford, Connecticut (left), and Madeleine Watson of Chicago August 1917 Sailors attacking pickets while policemen look casually on, summer 1917 (Library of Congress)

Sailors attacking pickets while policemen look casually on, summer 1917 (Library of Congress) Lucy Branham demands justice for imprisoned Alice Paul, late 1917

Lucy Branham demands justice for imprisoned Alice Paul, late 1917  Abby Scott Baker in prison dress, 1917. Baker was head of the NWP's lobbyist team (Library of Congress)

Abby Scott Baker in prison dress, 1917. Baker was head of the NWP's lobbyist team (Library of Congress) Dora Lewis of Philadelphia on release from jail after five days of hunger striking. Aug 1918

Dora Lewis of Philadelphia on release from jail after five days of hunger striking. Aug 1918 Wearing prison uniforms Doris Stevens, Alison Turnbull Hopkins, Eunice Dana Brannan speak during "prison special" tour 1919. An earlier "prison special" tour had attracted massive publicity in 1918

Wearing prison uniforms Doris Stevens, Alison Turnbull Hopkins, Eunice Dana Brannan speak during "prison special" tour 1919. An earlier "prison special" tour had attracted massive publicity in 1918 Suffrage protestors burn speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. September 16,1918

Suffrage protestors burn speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. September 16,1918  Police arresting party demonstrators outside Senate Office Building, Oct. 1918.

Police arresting party demonstrators outside Senate Office Building, Oct. 1918. Police arresting party picketers outside White House, August 1918

Police arresting party picketers outside White House, August 1918