|

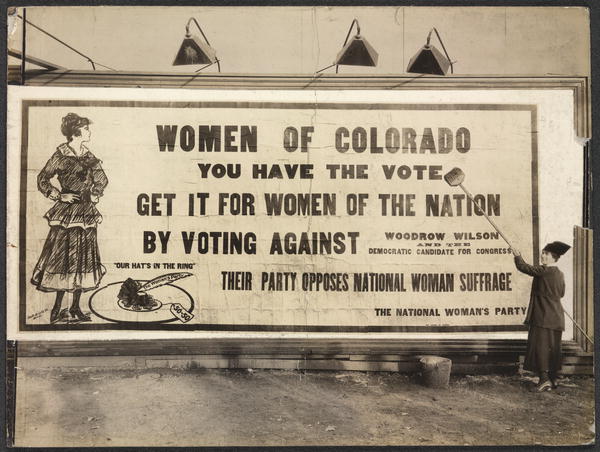

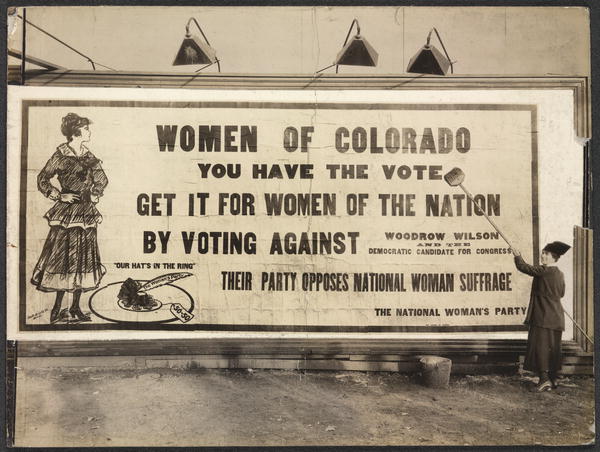

Part of the vast billboard campaign of the Woman's Party. Putting up billboard in Denver-- 1916

(Library of Congress)

by Sara Parolin and Monica Keosombath

Early in 1916, the Executive Committee of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage concluded that the movement needed to become a political party, a woman's party. The strategy of attacking the Democratic Party, the party in power and the party most resistant to suffrage demands, seemed to be working. In the western states where women had voting rights, the Democrats had lost congressional seats in 1914. Now as the nation prepared for the 1916 election cycle, Alice Paul wanted to double-down, arguing that a new independent party of women voters could tip the balance in key western states in the upcoming election.

In April, the CU Advisory Council met and approved plans for a June convention to launch the National Woman's Party.

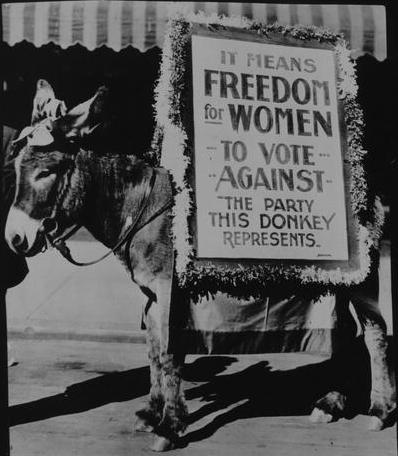

National Woman's Party demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, October 1916 National Woman's Party demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, October 1916

(Library of Congress)

Meeting in Chicago June 5-7, CU delegates enthusiastically endorsed plans for the new political party. The NWP pledged to exclusively focus on the passage of a constitutional amendment extending suffrage to women, an amendment often referred to as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. As an independent political party, members of the NWP would refrain from supporting any existing party until women were given the right to vote and worked to “punish” the dominant parties that did not support equal suffrage. The purpose was to not win the election as an independent party, but to represent a significant factor in votes for the Republican or Democratic Party. Paul pointed out that it would take only “9 per cent of the total vote cast in the presidential election in order to have thrown the election to the other party’” as she had observed in the previous election in 1912. Paul wanted the Woman’s Party to act as a balance of power between the political parties.[1] In her book, From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights, Christine Lunardini quotes Charles Beard's explanation of the role of a third party in a two-party system: “By agitation and by the use of marginal votes in close campaigns, minorities are able to force the gradual acceptance of some or all of their leading doctrines by one or the other of the great parties, and through inevitable competition between these parties, to educate the whole nation into accepting ideas that were once abhorrent.”[2]

But how was the NWP distinguishable from the NAWSA, the organization it grew out of? The first difference was their desired methods for winning voting rights. For NAWSA, the strategy was to focus on individual states, winning the vote by lobbying legislatures or through initiatives in states where ballot measures were allowed. The NWP single-mindedly pursued a congressional strategy designed to enfranchise women nationwide. Another key point of disagreement between the NWP and NAWSA was the Shafroth-Palmer Amendment. This NAWSA-endorsed constitutional amendment would require a state to hold a referendum on establishing voting rights women if eight percent of the voters in a previous election signed a petition. NAWSA reasoned that Congress was much more likely to move on this measure than the Anthony amendment because the Shaforth amendment allowed southern Democrats to excercise their demand for "state's rights" which had as much to do with restricting black voters as women voters.[3]

While plans were developing for the new party, the Congressional Union sought new ways to fund its increasingly ambitious campaigns. On February 20, 1916, the CU raised $8,000 from an opera and dinner hosted at the New York Waldorf Hotel by loyal supporter and suffragette Alva Belmont.[8] A month later, the wealthy Belmont donated an additional $1,000 to fund an organizing tour in the West to “form a woman’s voter party to help secure the passage of the national suffrage amendment in this session of Congress.”[9] Women in these states would represent over four million votes, and Paul’s goal was to prepare all women in suffrage states to participate in the election as an independent political party.

The western organizing tour began in April 1916 after a farewell ceremony of over 5,000 “suffragist sympathizers” and the 23 female envoys representing 36 disenfranchised states at Union Station in Washington, D.C.[10] By late April, the suffragist envoys reached Los Angeles, California, where they gave speeches advocating for national women’s voting rights to a crowd of over 200 people.[11] At the envoys’ next stop in San Francisco, Alice Paul confirmed the notion that the National Woman’s Party could nominate a woman for the presidential elections and that this was “possible and not improbable.”[12]

Nevada’s conference at the Majestic Theatre was met with enthusiasm as Lucy Burns and other representatives discussed strategic plans for a federal amendment for woman suffrage. Many women joined the Congressional Union after declaring that “they could make no better use of their first opportunity to vote in a national election than by using their power to help the cause of freedom for all the women of the country.”[13] The Nevada conference sent an important message to the Democrats, that the female vote could help or hurt their party.

Campaign in Colorado with National Woman's Party sign advocating opposition to Democratic Party October-November 1916 (Library of Congress) Campaign in Colorado with National Woman's Party sign advocating opposition to Democratic Party October-November 1916 (Library of Congress)

During the tour, the envoys also publicized their plans to hold the June convention of women voters to launch the new political party. The convention was to be held in Chicago immediately before the Republican and Progressive Parties’ national conventions. The goal of the NWP convention was to determine which existing political party would obtain these the four million votes that would be cast by women after the Susan B. Anthony Amendment was passed.[14] In response to this announcement, NAWSA leader Dr. Anna Howard Shaw argued that suffrage should not become a party issue.[15] . NAWSA planned to have their own convention in Chicago at the same time, where they would discuss and submit a resolution asking the Republican Party to include nationwide suffrage in their platform.[16]

The National Woman's Party and NAWSA attempted to reach the same end by different means. NAWSA leader Carrie Chapman Catt claimed that when the NWP asked for an amendment, they were only asking “for half the loaf,” while NAWSA asked for “the whole loaf” by working with established political parties and urging them to endorse national suffrage.[17] At their convention, the Republican Party accepted NAWSA’s suggestions and added a statement endorsing woman suffrage to their platform while rejecting the NWP demand that it endorse the Susan B. Anthony amendment, maintaining that it was within the states’ jurisdiction to decide whether women should have the right to vote.[18] However, as Lunardini writes, “while the Republicans and Democrats could bring themselves only to endorse suffrage while refusing to support a federal amendment, the Progressives, Socialists, and Prohibitionist parties all came out unequivocally for a federal woman suffrage amendment.”[19]

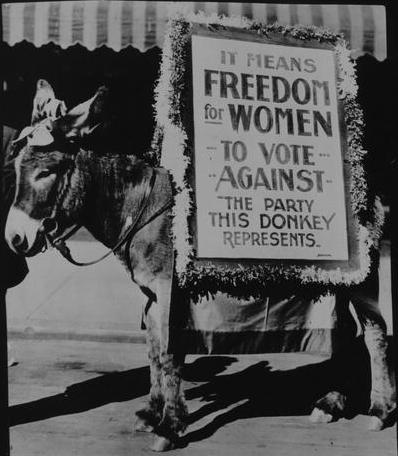

National Woman's Party Banner in Tucson condemns Wilson and Democratic congressional candidates, 1916 (Library of Congress) National Woman's Party Banner in Tucson condemns Wilson and Democratic congressional candidates, 1916 (Library of Congress)

As the election season progressed, NWP activists continued to attack Democratic candidates while promoting the amendment in various ways, staging rallies, setting up booths at county fairs, and protesting on the streets. The Suffragist stated that “at these fairs, booths have been maintained by the National Woman’s Party, at which the familiar purple, white and yellow colors have proclaimed their message to the throngs of visitors; thousands of pieces of literature have been distributed, and a continuous speaking campaign has carried the slogan, ‘Vote against Wilson and the Democratic Party.’”[20]

Although Alice Paul did not endorse the Republican Party, she applauded Presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes for supporting the woman suffrage amendment. Nevertheless, despite the NWP’s efforts in opposition to the Democratic Party, President Woodrow Wilson, whose platform included state jurisdiction of voting rights, was reelected in November. The NWP had worked hard to push the gender gap and female votes in enfranchised states may have worked against the Democrats, but not enough to make a difference.

<

[1] "Conference of Officers of the Congressional Union,” The Suffragist, April 16, 1916, p. 4.

[2] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986,p. 90.

[8] “Suffrage Operetta Gives Cause $8,000.” The New York Times, February 20, 1916, page 15.

[9] “$1,000 Gift to Suffrage.” The Washington Post, March 18, 1916, page 4.

[10] “Suffrage Heralds Go.” The Washington Post, April 10, 1916, page 2.

[11] “All Women to Have the Vote.” The Los Angeles Times,

[12] “May Run Woman for President.” The Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1916, page 12.

[13] “Enthusiastic Greetings of Envoys in Nevada,” The Suffragist, May 13, 1916, p. 3

[14] “Call Suffrage Party.” The Washington Post, April 9, 1916, page 16.

[15] “Dr. Shaw Opposed New Woman’s Party.” The Los Angeles Times, May 5, 1916, page 13.

[16] Women are Agitated by Two Conferences.” The Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1916, page 13.

[17] “Women Urge Plank Favoring Suffrage.” The New York Times, June 7, 1916, page 6.

[18] “Win a Suffrage Plank.” The Washington Post, June 9, 2016, page 3.

[19] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986, p. 91.

[20] “One Night Stand in Oregon,” The Suffragist, November 4, 1916, p. 7

|

National Woman's Party demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, October 1916

National Woman's Party demonstrating against Woodrow Wilson in Chicago, October 1916  Campaign in Colorado with National Woman's Party sign advocating opposition to Democratic Party October-November 1916 (Library of Congress)

Campaign in Colorado with National Woman's Party sign advocating opposition to Democratic Party October-November 1916 (Library of Congress)  National Woman's Party Banner in Tucson condemns Wilson and Democratic congressional candidates, 1916 (Library of Congress)

National Woman's Party Banner in Tucson condemns Wilson and Democratic congressional candidates, 1916 (Library of Congress)