by Cassondra St. Cyr, Anne Peterson, Taylor Franks

|

Activists watch Alice Paul sew a star onto the NWP Ratification Flag, signifying that another state has ratified. 1919 Igniting Victory (by Cassondra St. Cyr)After the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, marked the end of World War I, the NWP feared that the Wilson administration would push aside women’s suffrage to focus on post-war issues in Europe. Alice Paul believed a new strategy was needed to make sure that Wilson remained aware of them while in Europe and that pressure would increase on recalcitrant Congressmen. Events such as watchfires, prison speaking tours, and direct protests of the President brought increased visibility to the NWP and ensured that the federal suffrage amendment passed through both houses of Congress and began the state ratification process in 1919. The NWP had been demonstrating at the White House and in nearby Lafayette Park since 1917, primarily as “silent sentinels” who stood with banners. The suffragists first burned Wilson’s speeches in the fall and winter of 1918, but as 1919 began, the picket escalated to burning speeches continuously as he delivered them in Europe. When told of a speech, members would ring a bell at the NWP headquarters and then march to the park to set the watchfire.[1] The NWP held their protests near the statues of Lafayette and Rochambeau, two French revolutionaries and respected military leaders who aided in the American revolution and legitimized efforts to spread democracy abroad. The statues linked the NWP’s cause to the American revolutionary legacy and U.S. women’s suffrage to European women’s suffrage.[2]  NWP watchfires burn outside White House, Jan. 1919 (Library of Congress) NWP watchfires burn outside White House, Jan. 1919 (Library of Congress)

On New Year’s Day, 1919, a fire was lit in an urn in front of the White House and women began throwing copies of speeches in to feed it. The date was in honor of Joan of Arc: “the history of Joan of Arc is the history of women and government throughout the ages of the world. They offer sacrifice and service and are humiliated and denied.”[3] They opened banners with messages such as “President Wilson is Deceiving the World When He Appears as the Prophet of Democracy.” This led a group of sailors and soldiers to rush the women and overturn the urn to put the fire out. A second fire was then started in Lafayette Park, which was continuously rekindled. Per the Los Angeles Times, once police arrived, they made five arrests for “violation of park regulations.”[4] Those arrested refused to pay the fines and went to jail, claiming that payment was an admission of guilt. A New York Times article titled “Men in Uniform Rout Suffragists” said the protest was an example of the NWP’s “subversion.” The article described how one Army captain “stepped in…and called for three cheers for the President, ‘the world’s leader of democracy and the best friend the women of America ever had.’”[5] In contrast, The Suffragist’s retelling of the protest was much more positive and hopeful, mentioning passersby who voiced their support.  Suffrage protestors burn speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. September 16,1918 (Library of Congress) Suffrage protestors burn speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. September 16,1918 (Library of Congress)

The watchfires continued through the month of January and stirred anger and resistance. On January 7, women burned copies of a Wilson speech given in Italy while men sought to put the fires out. The arrested women again refused to pay bond and were jailed. On January 9, the NWP released a statement that said watchfires would continue despite the jailing because “the President had been converted but that considerable agitation would be needed to spur Congress to action.”[6] The fires embodied the contempt they had for Wilson’s “words unsupported by deeds” and attempted to force him to actualize his democratic commitments at home.[7] After burning speeches on January 13, twenty-five NWP members were attacked by a mob led by schoolboys. As the women lit new fires in Lafayette Park, the mob attacked NWP headquarters, pulling down the watchfire bell and destroying banners. This resulted in 18 arrests of women charged with building fires on government property, standing on the coping around the White House, and attempting to make disorderly speeches.[8] Police released 12 who then returned to the park and were arrested again. They refused to post bond and went on a hunger strike. The Washington Post reported the next day that officials were considering forcible feeding. On January 20, two NWP members walked a different route to the White House and lit a fire, along with four others who carried a banner from headquarters. Each produced a copy of a Wilson speech and burned it. All six were arrested, though released under bond.[9] The watchfires further escalated. On February 9, approximately 100 women who held a small parade and later burned speeches and an effigy of President Wilson before a crowd of 2,000. The New York Times described the effigy as a “huge doll stuffed with straw…slightly over two feet in height.”[10] D.C. police, military police, and Boy Scouts rounded up and arrested 39 women. 26 were jailed and all went on hunger strikes. NAWSA denounced the NWP for the protest, calling them the “I.W.W. of the suffrage movement,” intending to solidify the perceived link between the NWP and socialist, anarchist, or Marxist ideologies. [11] While the burning of the effigy was the most volatile, direct form of attack and would constitute the height of NWP militancy, watchfire protests continued until May.[12]  Speakers on Prison Special tour, San Francisco, 1919 (Library of Congress) Speakers on Prison Special tour, San Francisco, 1919 (Library of Congress)

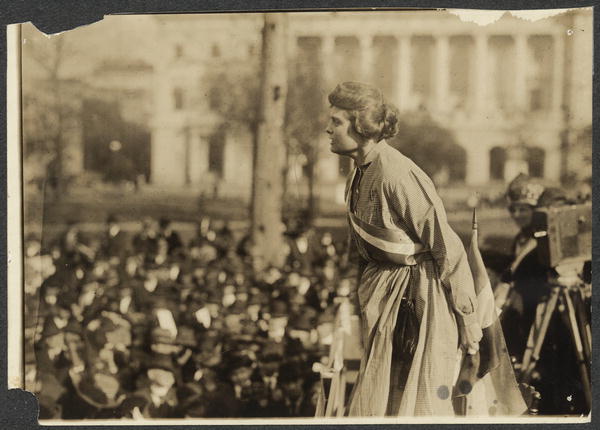

The NWP also began drumming up grassroots support in other direct ways. On January 27, the NWP announced a three-week train tour that would go cross-country and feature 26 women who had spent time in jail for picketing. Nicknamed the “Prison Special,” it left from Washington D.C. on February 15 and returned on March 10 after stopping in 15 cities. The NWP’s stated goal of the tour was to acquaint the country with the “brutal and lawless measures of the Administration to suppress suffrage.”[13] Their slogan was “From Prison to People” and they labeled their train the “Democracy Limited.” In each city, the women held mass meetings, gave speeches, described their tactics, and fundraised. They sang the “women’s Marseillaise,” a revolutionary freedom anthem and recounted the horrific jail conditions they endured. The women dressed in replica prison costumes and had intended to paint the outside of the railway car they were traveling in with bars and a door to mimic their prison cells, but the Railroad Administration would “not allow the painting of the cars to look like prison cells, nor any other insignia denoting the character or purpose of the car.”[14] This also prevented them from using any symbols or colors, such as their regular purple, gold, and white, that would have indicated their affiliation with the NWP. Nevertheless, the tour was very successful and brought them much-needed money and goodwill. A Suffragist article about the Prison Special described how their audiences in the West had “become a path of people freshly awakened to the deep importance of immediate national action.”[15] Some in the press were not as moved, with the Los Angeles Times describing a Chicago meeting as encouraging “decidedly unnatural feminine sentiments.”[16] Meanwhile, more direct protests were also in the works.  Lucy Branham in Occoquan prison dress speaking during Prison Special tour March 1919 Lucy Branham in Occoquan prison dress speaking during Prison Special tour March 1919 (Library of Congress) President Wilson was scheduled to return from the Paris Peace Conference in Boston, and the NWP planned to demonstrate during his speech there. The Boston Equal Suffrage Association denounced these plans, saying that they “deprecated any attempt of the NWP to annoy the President.”[17] On February 24, Wilson was greeted by an NWP protest at the Boston Commons, where they carried banners to remind him of his 1918 pledge to support women’s suffrage, to push for the last two votes in the Senate, and his advice to the Senate that government would be distrusted if it did not enfranchise women. The suffragists failed to secure the last two Senate votes by the March 3 recess. NWP members marched through a line of Marines trying to hold the crowds back, refusing to move aside, and burned speeches in front of the State House. Police arrested 21 women on charges of loitering and failure to obey a city ordinance. During the trial, they didn’t smile, avoided discussion, and refused to speak on subjects outside of women’s suffrage.[18] Sixteen of the 21 women received eight-day jail sentences. All went on hunger strikes and none of them tried to get bail. They indicated that they would attend a mass meeting if released. These were the last women imprisoned during the suffrage movement. The Washington Post reported that on February 27, an unknown person paid the fines of the suffragists and they were released. They began a formal protest, calling the payments illegal and “subterfuge.”[19] President Wilson had little respite from the February demonstration. He planned to speak about the League of Nations at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York on March 4 before returning to Europe. 200 NWP members protested the event. As Wilson spoke inside, NWP members recorded and copied down his words and sneaked the notes outside to Elsie Hill, who burned them with her torch.[20] The New York Times reported that, as Wilson left the Opera House, the pickets rushed the police cordon.[21] The women were attacked by a mob of sailors, soldiers, and police. A group of policemen beat the women with clubs, knocked them down, trampled them underfoot and rendered many unconscious, while others suffered bleeding from the hands and face, as well as twisted and bruised arms.[22]They also claimed that they had personal items stolen and $500 worth of banners destroyed.[23] The protest led to six arrests for disorderly conduct and charges of assaulting the police, but the women were released. This protest marked the peak of violence against the NWP during the year, but they still sensed an inevitable win. A new Congress would be coming in, and the NWP again shifted from direct protest to a massive, coordinated lobbying effort at the federal and state levels. The amendment passed through the House on May 21, 1919, and the Senate on June 4, 1919. 1920 campaign for ratification (by Anne Peterson and Taylor Franks)

Colorado ratifies suffrage amendment, December 12, 1919 (Library of Congress) Colorado ratifies suffrage amendment, December 12, 1919 (Library of Congress)

Unfortunately for the NWP, the campaign to achieve equal voting rights had only just begun. It was not until over a year later, in August 1920, that the amendment received all of the 36 states necessary for ratification, and it was not always a secure path to victory. Many male politicians still resisted ratification, and the southern and eastern obstructionists who had delayed the amendment’s passage in the Senate now sought to delay the ratification process long enough to prevent women from voting in the 1920 elections. Nevertheless, the NWP campaigned, polled, lobbied, and fundraised throughout the state-by-state ratification process. By 1920, most northern and western states had ratified the amendment, and according to one brief Washington Post article, some states were even scrambling to make the list of the first 36 states to ratify the amendment.[24] At the time of publication, approximately 28 million women were of voting age in the U.S., making them a potential political asset in the fall elections. This concept was certainly not lost on Senator James W. Wadsworth, Jr., who won the votes of Republican women despite disapproval from suffragists; he had been a strong member of the opposition to the federal women’s suffrage amendment.[25] He said it was important for woman to be involved in politics because the Republican Party needed their support. One of his female supporters said their party was lucky to have men of his principles and conviction, saying, “There can be no resentments for bygones in politics.” Mrs. James Griswold Wentz, President of the Women’s Republican Club, advocated for the Senator when he spoke at her club’s Lincoln Day luncheon. She claimed that it was the responsibility of Republican women to keep Republican men in office, and that supporters of the NWP should “get out of all outside parties and get into the Republican Party.”  National Woman's Party members picketing the Republican convention, Chicago, June 1920 National Woman's Party members picketing the Republican convention, Chicago, June 1920 (Library of Congress) In the South, a strong foundation of opposition to women’s suffrage remained. However, both men and women in the South made monetary contributions to the suffragist movement in the North. After ratification was defeated in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia, NWP member Mary Winsor said the “Suffrage South is ashamed of the refusal of Southern legislatures to do their share in giving women political freedom, and is eager to aid ratification work in other states.” [26] The NWP also sent out letters to various candidates who were running in the fall elections, and most said they supported women’s suffrage. The party also wrote to a prominent Washington D.C. figure who would one day become President; in 1920, Florence B. Bockel sent a letter to Herbert Hoover asking about his stance on women’s suffrage. In his reply, he stated that he had always supported women entering the political sphere, and even went so far as to say that it would “materially raise the whole political ideals of the United States.” [27] Legislatures continued to resist the NWP’s efforts, and the final battles were in courtrooms and state houses. In Ohio, the legislature sent ratification to a state referendum, which would have postponed action long enough to prevent women from being able to vote on the fall ballot. This case went to the Supreme Court, where the NWP requested an injunction against the referendum.[28] They were successful, as the court ruled that it was important for national unity that the matter of women’s suffrage be settled and not left undecided in Ohio or other states. In West Virginia, ratification passed through the one house of their bicameral legislature with an easy majority, while the state Senate found itself in a tie, 14-14. [29] Of the two representatives were missing, one was in favor of ratification and the other was against it. The one who supported suffrage was on vacation in California, and rushed back across the country in order to cast his vote. Luckily for the NWP, the other was no longer considered a representative because he had moved to Illinois and therefore forfeited his residency. At times, it was only by sheer luck that suffrage had enough support for full ratification. The year 1920 is characterized by the NWP’s fight for the final state ratifications, but another important milestone was women’s first campaigns for office. In April, former NWP chairwoman Anne Martin accepted a Republican nomination to run for the Senate, becoming the first woman to do so.[30] Shortly after this announcement, an NWP questionnaire revealed that most of North Carolina’s legislature favored the ratification of the amendment.[31] This meant that the women only needed one more state to succeed in their goal of obtaining the right to vote.  Party members picketing the Republican convention, Chicago, June 1920 (Library of Congress) Party members picketing the Republican convention, Chicago, June 1920 (Library of Congress)

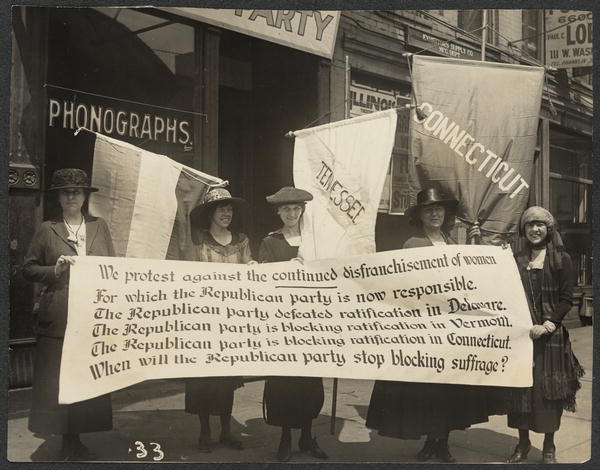

In May, Delaware failed to ratify the amendment. As soon as the NWP heard this news, they decided to picket the Republican National Convention in Chicago. According to the Los Angeles Times, “Every effort, Miss Paul said, would be directed to inducing national leaders to urge the Governors of Connecticut and Vermont to call special sessions of the Legislatures in their states and pass on suffrage.”[32] More than 100 women from 22 states participated in the peaceful protest, carrying banners with different slogans that urged the Republicans to help in their cause. Despite the NWP’s efforts, Connecticut and Vermont did not ratify the amendment. They then turned their efforts to the Democratic state of Tennessee near the end of June. Seeking to secure more influence on votes, the NWP looked to Senator Warren G. Harding. Though the Republican nominee did support suffrage, he refused to use his influence to force any Tennessee state executive to hasten suffrage.[33] Continuing their fight, Alice Paul announced that the NWP needed contributions for their campaign in Tennessee. Paul announced to the 50,000 members of the NWP they wanted at least $10,000 for their efforts to campaign and persuade the Tennessee legislature of calling a session to ratify the suffrage amendment.[34] The party received many contributions ranging from one dollar to $1,000. A California Senator sent $1,000 himself.[35] The NWP used the donated funds to set up headquarters throughout Tennessee, where they only needed 16 more votes from legislators. As of August 8, they had set up four headquarters throughout the state and had sent five organizers to campaign in districts of legislatures.[36] They also used the funds to protest outside Senator Harding’s home in Marion, Ohio. A newspaper article reported, “Five-hundred purple, white, and gold banners and two trunks of suffrage regalia will leave Washington tomorrow.”[37] Holding banners that read “A solid vote for suffrage,” the suffragists asked Harding to persuade other Tennessee Republicans to vote in favor of suffrage.  Alice Paul unfurls banner at National Woman's Party headquarters after Tennessee ratifies, becoming the 36th and final state needed for ratification, August 18, 1920 (Library of Congress) Alice Paul unfurls banner at National Woman's Party headquarters after Tennessee ratifies, becoming the 36th and final state needed for ratification, August 18, 1920 (Library of Congress)

On August 18, 1920, Tennessee ratified the amendment in their state legislature and ended the decades-long battle for women’s suffrage.[38] On that day, Alice Paul hoisted the ratification flag above the NWP headquarters in victory, replacing “the purple, white, and gold banner floating beside the American flag over the portico with another bearing eighteen gold and eighteen purple stars on the central bar of white.”[39] The flag symbolized the thirty-six states needed to ratify the amendment. But the NWP did not see their mission as complete or their purpose obsolete; after hoisting the flag, they went back to work to stop any remaining opposition to suffrage. The organization also had to look forward to what came after the vote for women. In an article titled “Militants Go Right On,” Paul said that the party planned to hold a convention in the Capitol after the ratification, where they would discuss their next goal in the fight for women’s equality.[40] The party would soon begin campaigning for the Equal Rights Amendment. Next: Ch5: Toward Equal Rights[1] Belinda A. Stillion Southard, Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913-1920. 1st ed. Presidential Rhetoric Series; No. 21 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011), 165. [2] Belinda A. Stillion Southard, Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913-1920. 1st ed. Presidential Rhetoric Series; No. 21 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011), 166. [3] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991), p. 236. [4] AP Night Wire, “Capital Suffragists are Roughly Handled,” Los Angeles Times, January 2, 1919, pg. 11 [5] “Men in Uniform Rout Suffragists,” New York Times, January 2, 1919, pg. 1 [6] “Defend Liberty Fires,” New York Times, January 10, 1919, pg. 7 [7] Belinda A. Stillion Southard, Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913-1920. 1st ed. Presidential Rhetoric Series; No. 21 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011), 166. [8] “Watchfire Bell is Pulled Down,” The Washington Post, January 14, 1919, pg. 7 [9] “Militants Start New Fire,” The Washington Post, January 21, 1919, pg. 8 [10] “Suffragists Burn Wilson in Effigy; Many Locked Up,” New York Times, February 10, 1919, pg. 1 [11] “Suffragists Burn Wilson,” NYT, Feb. 10, 1919, pg. 1 [12] Stillion Southard, Militant Citizenship, 168. [13] “The Prison Special,” The Suffragist, February 1, 1919, pg. 10 [14] “Railroads Ban Bars on Suffrage Special,” Los Angeles Times, January 30, 1919, pg. 11 [15] “The Prison Special Through the West,” The Suffragist, 3/22/1919, pg. 7 [16] “Women’s Wrongs Help Gain Women’s Rights: Ex-Prisoners Base Plea for Vote Mostly on Story of ‘Martyrdom’,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1919, pg. 12 [17] “Wilson Expected at Boston on Sunday,” The Washington Post, February 20, 1919, pg. 3 [18] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991), p. 241. [19] “Suffs Protest Release,” The Washington Post, February 28, 1919, pg. 5 [20] Belinda A. Stillion Southard, Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913-1920. 1st ed. Presidential Rhetoric Series; No. 21 (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2011), 167. [21] “Six Suffragettes Put Under Arrest,” New York Times, March 5, 1919, pg. 3 [22] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman's Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991), p. 243. [23] “Suffragists Say Police Hit Them,” New York Times, March 6, 1919, pg. 9 [24] “Women Nearer Complete Vote.” The Washington Post, January 20, 1920, pg.8 [25] “Republican Women Laud Wadsworth.” New York Times, February 13, 1920, pg. 17 [26] “Aid Suffrage with Money” The Washington Post, March 8, 1920, pg. 8 [27] “Hoover Comes Out For Women’s Suffrage” New York Times, March 22, 1920, pg. 3 [28] “Suffragists File Ohio Brief” The Washington Post, March 19, 1920, pg. 7 [29] “West Virginia to the Rescue” The Independent, March 27, 1920, pg. 481 [30] “Anne Martin, Candidate for Senate, Opposes Peace Treaty and League of Nations,” New York Times, April 5, 1920, p. 17. [31] “Suffragists Claim State: Assert Poll of North Carolina Legislature Indicates Ratification,” New York Times, April 26, 1920, p. 17. [32] “Women Pickets at Convention: Alice Paul Heads "Shock Troops" Against Delegates,” Los Angeles Times, June 7, 1920, p. 17. [33] “Harding Holds Out Hope For "Suffs," The Washington Post, June 23rd, 1920, p. 5. [34] “Suffragists Seek Funds for Tennessee,” New York Times, July 5th, 1920, p. 3. [35] “Give Money For Suffrage: Contributions From All Sections Send in Varying Amounts,” The Washington Post, July 7, 1920, p. 14. [36] “Women Seeking Sixteen Votes in Tennessee; Open Week's Drive before Special Session,” New York Times, August 8th, 1920, p. 11. [37] “Militants Send 500 Banners and Regalia for Use in Picketing Harding’s Home,” New York Times, July 20th, 1920, p. 9. [38] “Suffrage Ratification Ends Century Old Struggle For Women” Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1920, pg. 13 [39] “RATIFICATION FLAG IS FLYING.: Alice Paul Hoists Banner When News Received; Does Not Fear Reconsideration, She Declares; Leader of Suffrage Cause Issues Statement.” Los Angeles Times, August 18th, 1920, p. 12.

|