|

(Library of Congress)

Alice Paul and Lucy Burns (by Alyssa Bell)

Lucy Burns traded her academic career for the British suffrage movement after meeting briefly with the Pankhursts during a school holiday in England. She served as an organizer for the Women’s Social and Political Union and consequently spent time in prison, where she was force fed after participating in hunger strikes.[1] She served more total prison time, both at home in the States and abroad in England, than any other American suffragist.[2]

Lucy Burns, 1913 (Library of Congress) Lucy Burns, 1913 (Library of Congress)

Alice Paul grew up on the Quaker doctrine of service, discipline, and dedication, as well as equality of the sexes before God. As a child, she attended suffrage meetings with her mother, and understood women’s suffrage to be socially acceptable and spiritually sound. While studying social work at Woodbridge, England, she witnessed an attempted speech by Christabel Pankhurst at the University of Birmingham. The male audience, harshly opposed to women’s suffrage, shouted and coerced her offstage, causing university officials to cancel the event. Appalled by the difference between this speech and the suffrage meetings she attended as a child, Paul joined the WSPU for two years. During that time, she developed a deep understanding for militant strategies and tactics. She served time in prison for her participation in demonstrations and also engaged in hunger strikes.

After Paul completed her degree, she and Burns reunited in America and agreed that the suffrage movement would progress most efficiently with federal support. In December 1912, the women convinced the NAWSA to appoint them to the organization’s Congressional Committee, tasked with lobbying for a federal amendment.[3] Paul and Burns received only reluctant support from the NAWSA and were responsible for generating their own financial support and recruiting members.[4] Despite NAWSA’s disinterest in a constitutional amendment and its opposition to militancy, the women remained determined to drum up political support from Senators and Congressmen in Washington.

Women, including those representing the states of Wisconsin and Oregon, and delegations from Womans' clubs, assemble in first national suffrage parade, March 3,.1913 (Library of Congress) Women, including those representing the states of Wisconsin and Oregon, and delegations from Womans' clubs, assemble in first national suffrage parade, March 3,.1913 (Library of Congress)

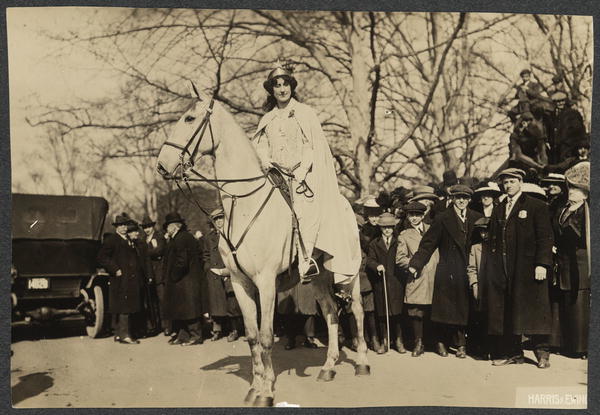

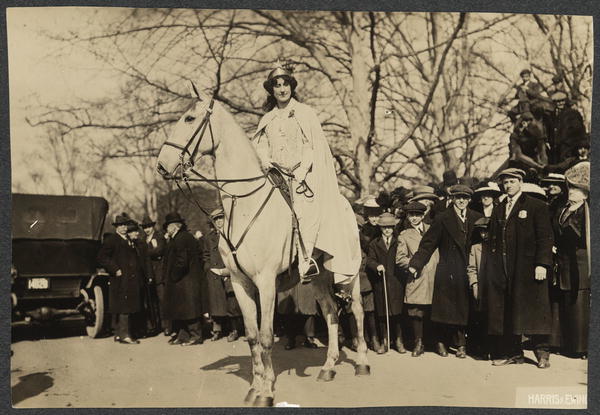

Immediately after their appointment to the committee, Paul and Burns organized a colossal parade for suffrage. Hoping that the massive demonstration would draw the attention of Congress and President-elect Woodrow Wilson, they planned the pageant-style parade on March 3, 1913, the day before Wilson’s inauguration.[5] Additionally, Alice Paul believed that the Democratic Party would be more inclined to pass a constitutional amendment if the public considered the entire party responsible for failing to produce favorable legislation for suffragists.[6] Moving down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., the parade mimicked British militant pageant demonstrations, boasting several bands, floats, and over 8,000 marchers.[7] Male spectators and the police jeered at the women marching in the procession, and although police had assured organizers that they would protect marchers during the event, they failed to intervene when men threatened and attacked the crowd.[8] While the parade drew front page newspaper coverage, the NAWSA remained skeptical of the Congressional Committee’s mild militancy and its effects on the reputation of the suffrage movement.

Inez Milholland Boissevain preparing to lead the March 3, 1913 (Library of Congress) Inez Milholland Boissevain preparing to lead the March 3, 1913 (Library of Congress)

Continued conflict between the Congressional Committee and the NAWSA led Alice Paul to form the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in April 1913. Despite their nearly identical executive boards, the Congressional Union operated as a separate organization from the NAWSA and began its own suffrage campaign focused on a federal amendment instead of state-by-state reform. Representatives were chosen from each Congressional district and built connections with local suffrage organizations in each region. Other members participated in meetings and conventions, demonstrations, letter writing and petition campaigns, membership drives, and regular gatherings with speakers.[9] The Congressional Union attracted a younger generation of well-educated women who were unsatisfied with the slow pace of the NAWSA and fascinated by the militancy of British suffragists. They also used the voting power of enfranchised women in the West, a source of strength largely ignored by the NAWSA, to pressure the Democratic Party. In addition, the organization approached President Wilson and other political leaders directly for their support. These acts horrified the NAWSA, who felt that antagonizing politicians would diminish public support and cause suffragists to be viewed as nagging and unrefined.[10] The NAWSA published several statements chastising its rowdy spawn, hoping to distance itself from public and political opposition to the Congressional Union.

First Congressional Union Headquarters (Library of Congress) First Congressional Union Headquarters (Library of Congress)

Escalating tensions between the Congressional Union and the NAWSA erupted at the NAWSA’s 45th annual convention in December 1913.[11] Alice Paul formally announced that the Congressional Union would campaign against all Democratic politicians in the looming elections if the party did not make drastic strides for women’s suffrage. The NAWSA leaders deemed such militancy inadmissible and presented Paul with an ultimatum: disband the Congressional Union and abandon the notion of holding the Democratic Party responsible, or forfeit her chairmanship of the Congressional Committee.[12]When Paul, Burns, and the remainder of the committee refused to yield, the NAWSA appointed a new Congressional Committee. NAWSA president Dr. Anna Howard Shaw publicly contradicted Alice Paul and the Congressional Union, stating that militant methods should not be adopted to bring about women’s suffrage.[13] In January 1914, the NAWSA accused the Congressional Union of failing to properly invoice finances, allowing British militancy to spoil suffragist ideology, and causing suspicion and mistrust of suffragists.[14] The two groups separated completely in February 1914 after the NAWSA board blocked the Congressional Union from being readmitted to the organization as an auxiliary member.[15]

Despite losing support from the NAWSA, the Congressional Union continued its suffrage campaign with vigorous militant energy.[16] The organization held countless meetings, rallies, and speeches, along with several large events including marches, automobile parades, and mass meetings with national delegates. To the public and the NAWSA, the Congressional Union appeared to be radical and militant. However, unlike those involved with the British movement, Paul and Burns had faith in the country’s democratic system and believed they could produce change with a modified militant strategy. Under the leadership of Alice Paul, a nonviolent Quaker, the American militant suffragist movement utilized less violent tactics than their British muses and instead focused on a general resistance against male authority.[17]

The National Woman’s Party formed amid tension between conflicting suffragist ideologies. But despite the rivalry between the NAWSA and the Congressional Union, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns succeeded in creating a militant organization that advocated for the rights of women through the remainder of the decade.

1914: The Congressional Union becomes independent (by Alyssa Crawford)

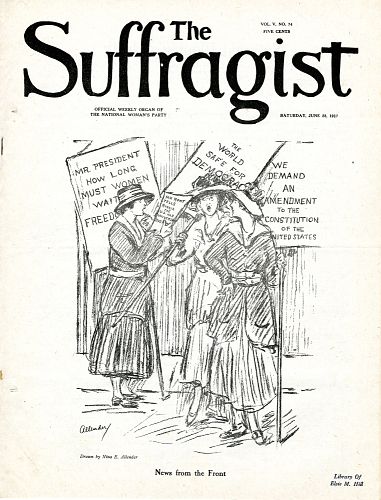

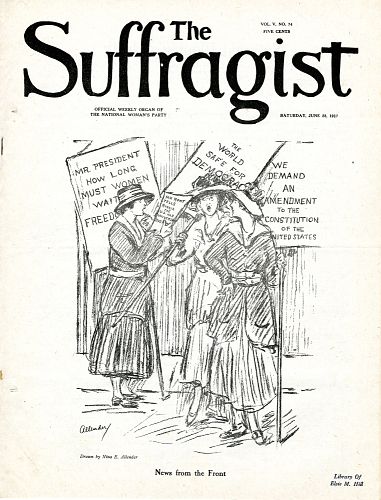

An issue of the Suffragist from 1917 An issue of the Suffragist from 1917

After the NAWSA voted to oust the Congressional Union, the group was free to move forward into “phase two of ‘pre-militancy.’”[18] One of their goals was to convince members of the Democratic Party to pass a federal amendment giving suffrage rights to women. This tactic, which Burns called “party in power,” was used by British suffragists to push responsibility onto the political party in power at the time.[19]

The Congressional Union also continued recruiting, expanding, and raising funds. Nearly every late-1914 issue of The Suffragist included a section dedicated to announcing new members. The Congressional Union even had a recruiting week from September 29, 1914 to August 1, 1914, where “members organized themselves into teams of five…each team determined to strive for the honor of securing the greatest addition to the membership of the Union.” [20] These recruitment efforts helped increase support for both state-level and national suffrage campaigns, as well as political candidates who supported women’s suffrage. Regularly scheduled meetings helped the Congressional Union cultivate public attention and raise the money needed to organize large demonstrations; they made $9,000 in their opening meeting alone.[21]

One of the most useful strategies the Congressional Union developed in 1914 was the use of propaganda. Thousands of readers subscribed to the weekly issues of The Suffragist. The Congressional Union also put on plays by women playwrights, which focused on topics related to women’s suffrage.[22] They also taught children about women’s suffrage by selling toys such as jig-saw puzzles.[23] The Congressional Union even published a song called “The March of the Women” in The Suffragist and encouraged readers to sing it during their next demonstration.[24]

To tie everything together, the Congressional Union usually decorated everything in purple, white, and gold, three colors used to signify both the Union and the women’s suffrage movement as a whole.

and Elizabeth Smith (right) working in the offices of The Suffragist, the weekly journal published by the Congressional Union and National Woman's Party from 1913 to 1921.jpg) Frances Pepper and Elizabeth Smith working in the offices of The Suffragist(Library of Congress) Frances Pepper and Elizabeth Smith working in the offices of The Suffragist(Library of Congress)

Another way the Congressional Union encouraged people to support their cause was by holding meetings and conventions. According to the January 17 issue of The Suffragist, over 400 people attended the Congressional Union’s opening rally where they discussed the events of the previous year, planned ahead for the current year’s events, and raised over $9,000.[25] After only a few months as a standalone organization, the Congressional Union was already popular.

The Union received similar support at two large conventions held later in the year, the Des Moines Conference held on March 29, 1914, and the Newport Conference held on August 29-30, 1914. During the Des Moines Conference, former NAWSA member Jane Addams discussed new aspects of the women’s suffrage movement and how the civic conditions of Chicago had improved since Illinois allowed women to vote.[26] She was met with much cheering and enthusiasm, as were other prominent speakers such as Iowa governor George W. Clark.[27] The Newport Conference was met with the same success and helped the Union raise over $7,000. Two versions of the federal suffrage amendment were being discussed in Congress at the time, and one goal of the conference was to determine which version suffragists should support. Delegates from over 17 suffrage groups agreed to get behind the Bristow-Mondell amendment.[28]

Members of the Congressional Union pasting advertisements announcing the procession on May 9th, 1914. (Library of Congress) Members of the Congressional Union pasting advertisements announcing the procession on May 9th, 1914. (Library of Congress)

In March 1914, the NAWSA “attempted to undermine the work of the CU by having another, complicated suffrage amendment proposal introduced that would effectively leave the power to enfranchise women with the states.”[29] The NAWSA named their amendment the Shafroth-Palmer Amendment. In order to make a distinction between the NAWSA’s amendment and the Congressional Union’s, Paul renamed the Bristow-Mondell Amendment as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment.

The Congressional Union’s demonstrations brought them the attention and support they needed. The first demonstration of the year began on January 6, 1914, when five women left the Congressional Union headquarters in D.C. and started a walk to Annapolis, Maryland, to present a piece of legislature to the House of Representatives when they convened the next afternoon. They were joined by a delegation of suffragists in Baltimore on the first day and even more suffragists once they reached Annapolis the next day. Bystanders also joined the march, and the crowd appeared before the House to petition them to pass a women’s suffrage amendment.[30]

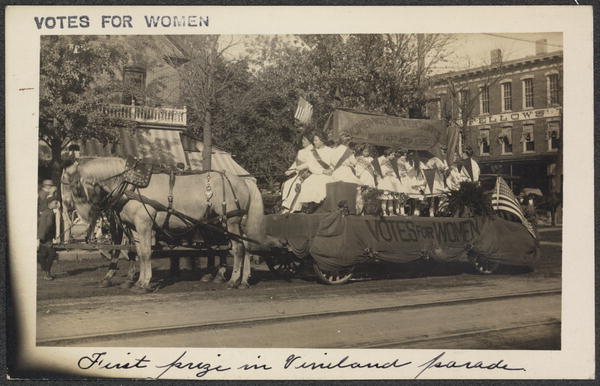

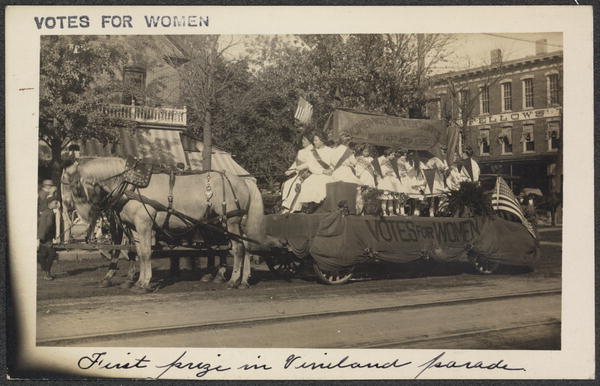

Votes for Women. First prize in Vineland, New Jersey, parade April 1, 1914 (Library of Congress) Votes for Women. First prize in Vineland, New Jersey, parade April 1, 1914 (Library of Congress)

The Union’s next major event was the April 21 suffrage ball. Over 800 people attended, including powerful guests such as Supreme Court Justice Holmes. The Suffragist described the night as a resounding success and by far the most successful social event of the season in Washington, gaining plenty of profit and attention from higher figures.[31]

The nationwide demonstration on May 2 was by far the highlight of the year for the Congressional Union. Planning for this event started in February 1914, when the Union sent representatives to the North, East, South, and West to plan and organize.[32] When the day finally came, there were demonstrations in all states. Delaware saw its first-ever suffragist display that year with a parade and floats. St. Louis had an automobile parade with several prominent speakers along the way. Chicago, Boston, and Pennsylvania put on massive parades, with 5,000 marchers participating in Chicago, 9,000 in Boston, and 2,000 women and 200 men in Pennsylvania. St. Paul suffragists joined a mile-long parade in Minneapolis after their own demonstration. Baltimore, New York, and New Jersey celebrated with state-wide suffrage rallies and open-air meetings. New York also had a massive automobile parade with nearly 100 cars from the Congressional Union, the Men’s League, the Women’s Suffrage Party, the New York State Association, and the Equal Franchise.[33] It was most widespread and successful event organized by the Congressional Union.

A week later on May 9, while Connecticut suffragists held a parade and a pageant, the Congressional Union held another demonstration in Washington D.C. [34] The day began with open-air meetings, speakers, and fundraisers. Later in the afternoon, a procession of thousands of women, three hundred children, ten bands, banner bearers, and an automobile procession traveled two miles from Lafayette Square to the Capitol building. When they reached the Capitol steps, leaders of the procession met and shook hands with Senators and Representatives who came out to greet them.[35]

After this procession, the Congressional Union focused on expanding the suffragist movement in other states, beginning campaigns in Nevada, Louisiana, Montana, and other disenfranchised states.[36] Even though the Congressional Union was gaining momentum, they still didn’t have strong footholds in every state, so local suffrage groups mainly oversaw these campaigns. Congressional Union delegates traveled from Washington D.C. to offer help and advice in raising money or planning smaller events.

By the end of the summer, even though Nevada and Montana were now suffragist states, the Democratic Party was still refusing to talk about women’s suffrage. In an effort to make Democrats realize that opposing the women’s suffrage amendment would lead to a loss of public support, the Congressional Union used letters, posters, and flyers to encourage voters not to vote for Democratic congressional candidates.[37] The campaign didn’t remove a large number of Democrats from Congress, but it certainly lowered their majority and showed the power of the suffragists.[38] The rest of the year was spent making final preparations for 1915.

1915: The Woman Voters Convention (by Zach Thomas and Samantha Han)

Members of the Congressional Union holding part of the 18,000 foot petition with 500,000 names delivered from San Francisco December 1915. (Library of Congress) Members of the Congressional Union holding part of the 18,000 foot petition with 500,000 names delivered from San Francisco December 1915. (Library of Congress)

On January 12, 1915, the Susan B. Anthony amendment was debated for more than 10 hours in the House of Representatives before failing to attain the two-thirds majority needed, with only 174 votes for and 204 votes against. Dr. Shaw, president of the National Suffrage Association, said, “I am not gratified, but the vote was better than I had expected.”[39] Though suffragists were aware that they did not yet possess the support necessary to get an amendment ratified, the vote still brought the cause greater national attention, as is evident by the front-page article in the New York Times.

During the rest of 1915, the suffragists focused on three tasks: gaining national attention, expanding their reach to areas where they had little influence, and pressuring representatives to publicly support suffrage.

The Congressional Union used aggressive tactics to gain attention, and the media often portrayed them as extremists. When President Wilson went on a tour to prepare Americans for war, he was followed by Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and other Union members until he agreed to meet with them in Mabel Vernon, Kansas.[40] In May 1915, when the President refused to see a group of suffragists in Washington D.C., they snuck past secret service agents and shouted across a crowded room to him. Alice Paul encouraged the women to conduct a sit-in for three days despite political and public opposition. Though they never committed or threatened acts of violence, the event was described as a militant act.[41]

The NWP’s numbers soon grew large enough to host conventions and lead large processions. These efforts marked a turning point as the NWP gained more members, attention, and power.

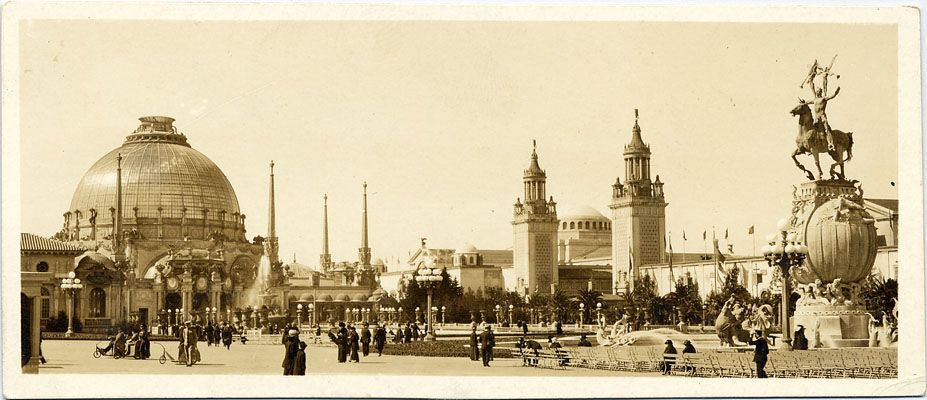

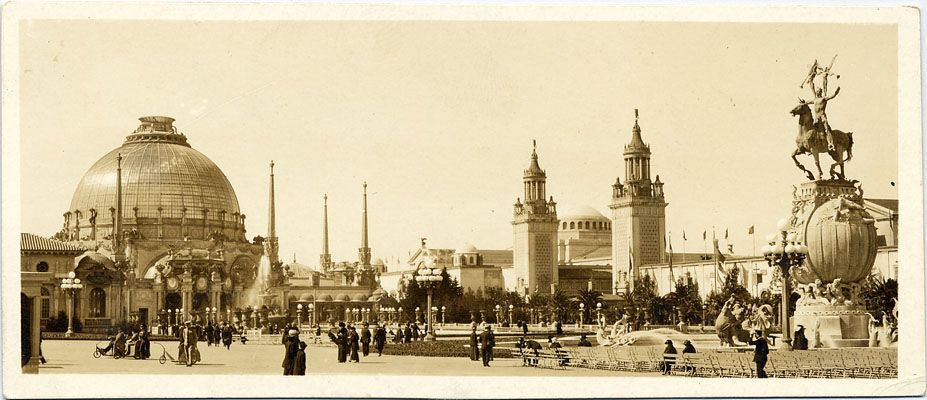

The Congressional Union used the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco as an organizing opportunity and held the Woman Voters Convention in September. (San Francisco Library) The Congressional Union used the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco as an organizing opportunity and held the Woman Voters Convention in September. (San Francisco Library)

The Woman Voters Convention, held from September 14 to September 16 in San Francisco, was covered in newspapers across the country. Paul “went to extraordinary lengths to create a spectacular event that was certain to attract nationwide attention.”[42] The convention coincided with the the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition, the 1915 San Francisco world's fair that brought hundreds of thousands of visitors to the city. The CU maintained a booth at the fair and staged a number of attention getting activities.[43] Hazel Hunkins climbed aboard a bi-plane and flew over the city dropping suffrage pamphlets from the sky. Numerous notable men and women gave speeches on suffrage, including former President Theodore Roosevelt, Helen Keller and her teacher Annie Sullivan Macey, and Italian educator Maria Montessori.

Suffrage envoys Sara Bard Field, Maria Kindberg, and Ingeborg Kindstedt during their cross-country journey to present suffrage petitions to Congress, September-December 1915 (Library of Congress) Suffrage envoys Sara Bard Field, Maria Kindberg, and Ingeborg Kindstedt during their cross-country journey to present suffrage petitions to Congress, September-December 1915 (Library of Congress)

More than 500,000 signatures were collected for a petition on women’s suffrage. The 18,000 foot long petition with its half million signatures was later driven across country by NWP organizer Sara Bard Field and two companions who spent months negotiating the often unpaved cross-country road network and dealing with mechanical breakdowns while stopping in towns and cities to publicize the journey and the petition. In December, the petition reached Washingon DC and President Wilson agreed to receive it in the East Room of the White House.[44] Though he was impressed by the “four-mile petition bearing 500,000 signatures, rolled on huge spools,” he maintained his party’s policy that suffrage was a state’s issue. [45] [46]

Smaller scale events, including suffrage teas, pageants, soapbox speeches, and luncheons, drew interest throughout the year and kept up the morale of those already involved.[47] [48]

Sara Bard Field speaking at Salt Lake City, Oct. 4, 1915, during her cross-country auto journey. Goverrnor Spry of Utah and Mayor Park of Salt Lake City are in attendance. (Library of Congress) Sara Bard Field speaking at Salt Lake City, Oct. 4, 1915, during her cross-country auto journey. Goverrnor Spry of Utah and Mayor Park of Salt Lake City are in attendance. (Library of Congress)

The suffragists also expanded their reach by establishing new affiliates in places where they previously had little influence. It took an additional year-and-a-half for the Congressional Union to establish affiliates in the remaining states, but once they did, they had a substantial base from which to work on the federal amendment.[49] As always, the Congressional Union and NAWSA did not play nice during this expansion period. Tensions increased as NAWSA found it more and more difficult to keep up with the Congressional Union’s expansion and even found themselves losing current affiliates to their rival. The Woman’s Political Union of Connecticut, after losing another suffrage vote in the state legislature, voted unanimously to apply for affiliation with the Congressional Union and proclaimed that the Union was “striving to bring about the only practical method for obtaining woman suffrage by working for the passage of the … amendment to the Federal Constitution.”[50] The Congressional Union even found success in establishing new affiliates and recruiting members in the west and south, where there had been little previous success by either them or NAWSA.[51] [52]

Suffrage envoys from San Francisco greeted in New Jersey on their way to Washington to present a petition to Congress with more than 500,000 signatures. (Library of Congress) Suffrage envoys from San Francisco greeted in New Jersey on their way to Washington to present a petition to Congress with more than 500,000 signatures. (Library of Congress)

The suffragists pressured specific representatives into publicly supporting women’s suffrage. At a public vote held in New York City’s Grand Central Palace on March 13, 1690 women and 956 men voted for suffrage and only 59 women and 131 men voted against it.[53] Votes like this supported the suffragists’ claim that a congressman must support suffrage in order to properly represent his constituents. Most representatives, such as Virginia’s Representative Carlin, gave in to the wishes of their constituents,[54] but some proved less willing to budge on the issue. Representative Fitzgerald of New York gave less than a minute of his time to a group of 25 suffragists he had agreed to meet and later commented, “If we gave our time to any and every deputation that wanted to talk to us, we could accomplish nothing.”[55] When asked by a large delegation of women representing NAWSA to support the Bristow-Mondell bill, Senator James O’Gorman responded, “I will not vote for this or any other woman suffrage amendment.”[56]

Despite the impressive list of pro-suffrage representatives, the suffragists continued to struggle gaining President Wilson’s support; they had very little success in even obtaining appointments with him.[57] [58] President Wilson said that, as the leader of the Democratic Party, he must support the party’s platform that suffrage was an issue to be decided by the states. However, on October 19, President Wilson announced that as a private citizen he would be voting to endorse a federal suffrage amendment in his home state of New Jersey.[59] This was a massive win for the suffragists. Referring to the Congressional Union’s Women Voters’ Convention in San Francisco, President Wilson said, “I know of no body of persons comparable to a body of ladies for creating an atmosphere of opinion. I have myself in part yielded to the influence of that atmosphere, for it took me a long time to observe how I was going to vote in New Jersey.”[60] Two of President Wilson’s daughters had begun participating in Congressional Union activities.[61]

[1] "Historical Overview of the National Woman’s Party”, The Library of Congress, Web.

[2] Kristina Grupta, "Lucy Burns", Education & Resources, National Women's History Museum, Web.

[3] Historical Overview of the National Woman’s Party”, The Library of Congress, Web.

[4] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party 1912-1920 (Lanham, 1991), pp 5-7, 46-59.

[5] Suffragists Take City for Pageant”, The Washington Post, March 3, 1913, p. 1.

[6] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party 1912-1920 (Lanham, 1991), pp 5-7, 46-59.

[7] Suffragists Take City for Pageant”, The Washington Post, March 3, 1913, p. 1.

[8] “Historical Overview of the National Woman’s Party”, The Library of Congress, Web.

[9] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party 1912-1920 (Lanham, 1991), pp 5-7, 46-59.

[10] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party 1912-1920 (Lanham, 1991), pp 5-7, 46-59.

[11] “Suffragist Forces Gather in Capital”, The New York Times, November 30, 1913, p. 2.

[12] “Historical Overview of the National Woman’s Party”, The Library of Congress, Web.

[13] “Militancy Unnecessary”, Los Angeles Times, December 6, 1913, p. 13.

[14] “Suffragist Rivals Now in the Field”, The New York Times, January 5, 1914, p. 3.

[15] “Historical Overview of the National Woman’s Party”, The Library of Congress, Web.

[16] “Suffragists on Warpath”, The New York Times, January 11, 1914, p. 3.

[17] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party 1912-1920 (Lanham, 1991), pp 5-7, 46-59.

[18] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party, 1912-1920 (Maryland: University Press of America, 1991), 59.

[19] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party, 1912-1920 (Maryland: University Press of America, 1991), 58.

[20] “Recruiting for the Congressional Union,” Suffragist, Aug. 1, 1914.

[21] “Opening Meeting for 1914 of the Congressional Union,” Suffragist, Jan. 17, 1914.

[22] “Suffrage Play,” Suffragist, Jan. 3, 1914.

[23] “Suffrage Game,” Suffragist, Jan. 3, 1914.

[24] “The March of the Women,” Suffragist, May 9, 1914.

[25] “Opening Meeting for 1914 of the Congressional Union,” Suffragist, Jan. 17, 1914.

[26] Ford, Linda. Iron-Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party, 1912-1920 (Maryland: University Press of America, 1991), 46.

[27] “Des Moines Conference Opens”, Suffragist, Apr. 4, 1914.

[28] “The Newport Conference,” Suffragist, Sept. 5, 1914.

[29] Cahill, Alice Paul, the National Woman’s Party and the Vote, 20.

[30] “Pilgrimage to the Opening of the Maryland Legislature,” Suffragist, Jan. 10, 1914.

[31] “Suffrage Ball a Huge Success,” Suffragist, Apr. 25, 1914.

[32] “May 2nd Demonstration,” Suffragist, Feb. 14, 1914.

[33] “The Greatest Suffrage Day,” Suffragist, May 9, 1914.

[34] “Connecticut Lining Up,” Suffragist, Feb. 28, 1914.

[35] “Bristow-Mondell Resolution Demanded by Thousands of Marchers,” Suffragist, May 16, 1914.

[36] “Holiday Campaign,” Suffragist, June 20, 1914.

[37] “Election Plans,” Suffragist, Sept. 26, 1914.

[38] “Results of the Election Campaign,” Suffragist, Dec. 19, 1914.

[39]“Suffragists Lose Fight In The House,” The New York Times, Jan 13, 1915, p. 1.

[40] Cahill, Alice Paul, the National Woman’s Party and the Vote, 22.

[41] Suffragists Harry President’s Guards, The New York Times, May 28, 1915, pg. 8.

[42] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986, p. 78.

[43] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[44] Ask Vote of Congress, The Washington Post, Sep 16, 1915, pg. 2.r f4

[45] “The Women Voters’ Envoy Present Their Message to the President and to Congress”

[46] March For Suffrage: Gorgeous Parade Is to Escort Envoys From West Today, The Washington Post, Dec 6, 1915, pg. 1.

[47] Busy Week for Suffragists, The Washington Post, July 29, 1915, pg. 4.

[48] Dance Given For D.A.R., The Washington Post, April 20, 1915, pg. 10.

[49] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[50] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[51] 4,000,000 Women Votes, The Washington Post, Aug 15, 1915, pg. 4.

[52] M’Kelway For Suffrage, The Washington Post, Feb 15, 1915, pg. 3.

[53] Big Vote For Suffrage, New York Times, Mar 14, 1915, pg. 4.

[54] Suffragists to See Carlin, The Washington Post, July 23, 1915, pg. 7.

[55] Suffragists are Snubbed, Los Angeles Times, June 18, 1915, pg. 14.

[56] Suffragettes Raise Siege, New York Times, May 8, 1915, pg. 12.

[57] Suffragettes Raise Siege, New York Times, May 8, 1915, pg. 12.

[58] Suffragists Harry President’s Guards, New York Times, May 23, 1915, pg. 5.

[59] Is Won To Suffrage, The Washington Post, Oct 7, 1915, pg. 2.

[60] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

[61] Lunardini, Christine A. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928. (New York: New York University Press), 1986.

|

Lucy Burns, 1913 (Library of Congress)

Lucy Burns, 1913 (Library of Congress) Women, including those representing the states of Wisconsin and Oregon, and delegations from Womans' clubs, assemble in first national suffrage parade, March 3,.1913 (Library of Congress)

Women, including those representing the states of Wisconsin and Oregon, and delegations from Womans' clubs, assemble in first national suffrage parade, March 3,.1913 (Library of Congress)  Inez Milholland Boissevain preparing to lead the March 3, 1913 (Library of Congress)

Inez Milholland Boissevain preparing to lead the March 3, 1913 (Library of Congress)  First Congressional Union Headquarters (Library of Congress)

First Congressional Union Headquarters (Library of Congress)  An issue of the Suffragist from 1917

An issue of the Suffragist from 1917 and Elizabeth Smith (right) working in the offices of The Suffragist, the weekly journal published by the Congressional Union and National Woman's Party from 1913 to 1921.jpg) Frances Pepper and Elizabeth Smith working in the offices of The Suffragist(Library of Congress)

Frances Pepper and Elizabeth Smith working in the offices of The Suffragist(Library of Congress)  Members of the Congressional Union pasting advertisements announcing the procession on May 9th, 1914. (Library of Congress)

Members of the Congressional Union pasting advertisements announcing the procession on May 9th, 1914. (Library of Congress)  Votes for Women. First prize in Vineland, New Jersey, parade April 1, 1914 (Library of Congress)

Votes for Women. First prize in Vineland, New Jersey, parade April 1, 1914 (Library of Congress)  Members of the Congressional Union holding part of the 18,000 foot petition with 500,000 names delivered from San Francisco December 1915. (Library of Congress)

Members of the Congressional Union holding part of the 18,000 foot petition with 500,000 names delivered from San Francisco December 1915. (Library of Congress)  The Congressional Union used the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco as an organizing opportunity and held the Woman Voters Convention in September. (San Francisco Library)

The Congressional Union used the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco as an organizing opportunity and held the Woman Voters Convention in September. (San Francisco Library)  Suffrage envoys Sara Bard Field, Maria Kindberg, and Ingeborg Kindstedt during their cross-country journey to present suffrage petitions to Congress, September-December 1915 (Library of Congress)

Suffrage envoys Sara Bard Field, Maria Kindberg, and Ingeborg Kindstedt during their cross-country journey to present suffrage petitions to Congress, September-December 1915 (Library of Congress)  Sara Bard Field speaking at Salt Lake City, Oct. 4, 1915, during her cross-country auto journey. Goverrnor Spry of Utah and Mayor Park of Salt Lake City are in attendance. (Library of Congress)

Sara Bard Field speaking at Salt Lake City, Oct. 4, 1915, during her cross-country auto journey. Goverrnor Spry of Utah and Mayor Park of Salt Lake City are in attendance. (Library of Congress)  Suffrage envoys from San Francisco greeted in New Jersey on their way to Washington to present a petition to Congress with more than 500,000 signatures. (Library of Congress)

Suffrage envoys from San Francisco greeted in New Jersey on their way to Washington to present a petition to Congress with more than 500,000 signatures. (Library of Congress)