by Sarah Guthu

Glenn Hughes, the first regional director of Washington State's Federal Theatre Program, who also worked to improve and expand the drama program at the University of Washington. (Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)

The Federal Theatre Project was a New Deal program (1935-1939) designed to provide relief for unemployed theatre artists. The vision of its national director, Hallie Flanagan, was also to develop a rich, regional, accessible theatre scene across the nation, with local theatres responsive to local issues. The FTP program in Washington State was one of the most successful in the country, and helped to revive and reimagine theatre in Washington, during the Great Depression, founding a Children’s Theatre, the Negro Repertory Company, and contributing to the emergence of a strengthened drama program at Seattle’s University of Washington.

The first director of the Federal Theatre Project in Washington State was Glenn Hughes, a dynamic University of Washington professor who worked throughout the 1930s to improve the position and profile of the young University drama program, which was still a division of the English department at the time. Hughes guided the program’s early development, emphasizing actor training. In 1934, the small Studio Theatre at Meany Hall opened, providing Hughes a venue in which his students could practice the demanding experience of a long run—in the 1930s, their college productions were mounted for six weeks at a time. Hughes also mounted shows in Meany Hall, and in the Penthouse suite of the Edmund Meany Hotel in Seattle, providing a range of venues and staging approaches (performances in the Penthouse suite, for example, were always staged in the round). Hughes’s vision also emphasized the importance of attracting younger audiences and from 1930 on, the program included courses in puppet theatre. By 1936, the University of Washington Puppeteers became the program’s first touring company. Children’s Theatre, another important part of the University’s program, would develop in the early 1940s.

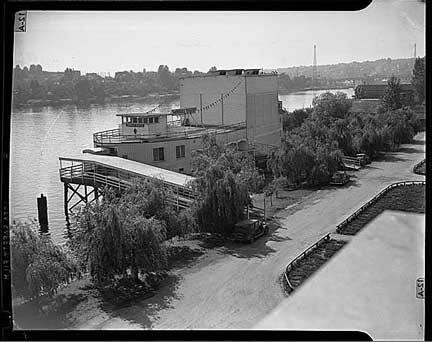

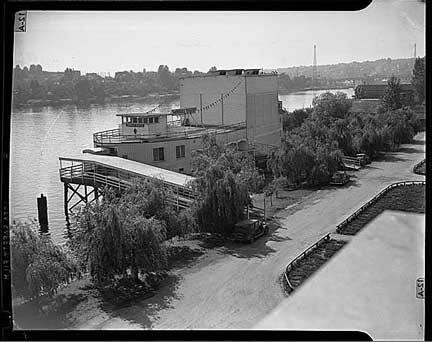

In 1936, Hughes assumed the leadership of the region’s branch of the Federal Theatre Project (FTP). Though Hughes would only stay until 1937, his work with the Federal Theatre Project and his contacts with the Works Progress Administration continued to advance the University’s theatre program. In 1938, Hughes acquired WPA funds to build the Showboat Theatre in 1938, a faux Mississippi steamer boat housing a revolving stage that sat on pilings at the University’s Portage Bay waterfront. Hughes also earmarked FTP support to fund a research project in theatre history, hiring individuals to cull Washington newspapers and records in order to create a comprehensive record of theatre in Washington State. Hughes also created a model theatre program, in which theatre artists crafted incredibly skillful and detailed scale models of six famous theatres. These large artifacts—an average measurement is approximately four feet wide by eight feet long—were so impressive (a model of a Roman theatre based on the Theatre at Orange, for example, features dozens of hand-carved scale statues) that they became the source of a fight for ownership between Hughes and the Federal Theatre Project’s national director, Hallie Flanagan. To this day, the models remain in Washington, currently displayed at A Contemporary Theatre in downtown Seattle—a testament to the high level of artistic skill of Washington’s theatre artists.

The Showboat Theatre in Portage Bay, near the University of Washington, 1941.(Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)

Under Hughes’s aegis, the theaters at the University of Washington were open six nights a week through most of the year. Hughes used light drawing-room fare in the Penthouse staging (and later in the Penthouse Theatre, a small Art-Deco-style arena theatre space built by the Works Progress Administration and opened in 1940) to lure film audiences back to the theatre, and puppet theatre and children’s theatre to connect with and develop a new generation of theatre audiences. Hughes’s FTP theatre history program compellingly displayed the academic rigor of the University’s drama program, in addition to its active production capabilities.

Burton James had also applied but failed to be appointed as director of the newly formed regional branch of the Federal Theatre Project. Nevertheless, the Seattle Repertory Playhouse found a way to be involved with the federal program and to enjoy the benefits of government subsidies for some of its activities. The Jameses proposed the formation of a Negro unit of the Federal Theatre Project at the Seattle Rep, a suggestion which was enthusiastically supported by FTP national director Hallie Flanagan. Though the Seattle Negro Repertory Company would only operate under the Jameses’s sponsorship until 1937, the Company continued to thrive after the Jameses resigned from the Project in 1937, their work’s popularity all the more remarkable given that Seattle’s African American population was so small and the Company’s enthusiastic audiences included whites in a city still marked by racial prejudice. Indeed, the company’s production of Stevedore was so powerfully affecting that an audience of Seattle dockworkers left their seats to join the actors onstage and help to build the barricade featured in the play’s final scenes.

The Penthouse Theatre at the University of Washington, which was built with WPA funds and opened in 1940. The Penthouse was designed by Glenn Hughes, and was the first theater in the round in the United States. (Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry photograph collection.)

In addition to (and sometimes in concert with) this collaboration with active academic and civic theatres in Washington State, Region Five of the Federal Theatre Project (based in Seattle) supported four distinct companies during the latter half of the 1930s. The Negro Repertory unit, mentioned above, operated under the Jameses’s guidance until 1937, and was occasionally cast with the Tacoma Unit (the Federal Theatre Project’s “white” actors), in productions like Power. After Power, the Jameses resigned, and the two units were consolidated into one space in the Federal Theatre building in Rainier Valley. The consolidated theatre was not a success, however. The Federal Theatre had leased it in an attempt to create a permanent home for the FTP and to minimize the expense involved in continually renting the larger houses in downtown Seattle for FTP productions, but the theatre was cramped and too far from Seattle to attract regular audiences. Later director Edwin O’Connor inevitably found himself leasing larger spaces for high-profile productions, such as the 1938 Negro Repertory Company’s production of Evening with Dunbar.

The Act II "work scene" from the Negro Repertory Company production of An Evening with Dunbar in Seattle, 1938. The gang is singing work songs and hammering with fluorescent-painted hammers. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection #236), box 4, folder 9.)

Less well-known is the Federal Theatre’s vaudeville unit, one of the first acting units formed in Region Five. As Glenn Hughes held auditions for the Project, he was startled to find that many of the eligible applicants (that is, former theatre workers who were now unemployed) in the region were vaudevillians, a testament to the long popularity of variety and vaudeville in the Northwest. Hughes decided to create a separate Variety Company as a part of the Northwest FTP. These performers were routed onto touring circuits of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps. The CCC, another New Deal program, fed, housed, dressed, and employed young men in various forest-management and parks projects, allowing them the opportunity to learn marketable trade skills and to aid their families by sending a majority of their paychecks home. Focusing on soil and water preservation, the CCC in Washington State built many state parks, laying roads and cutting trails, and erecting shelters, bathrooms, kitchens, and steps and guardrails on trails and campgrounds. As the CCC camps were located in far-flung wilderness areas, the travelling FTP troupes brought much-appreciated contact and outside entertainment to CCC workers.

Barry Witham's book is the major source on the Federal Theatre Project and especially about the Seattle unit. This essay relies heavily on the book.

Though not intended to be used as a political tool, some of the Tacoma Unit’s most successful and memorable productions were of Living Newspaper plays. These plays, one of Hallie Flanagan’s pet projects, brought contemporary social and political issues to the theatre, incorporating the new technologies of projected slides and film, voiceovers, and sound recordings with live performance. Flanagan believed in the compelling nature of fact, but wanted to use multimedia to mimic onstage the physical form of a newspaper, which might juxtapose an advertisement with a news article, or feature sparring editorials in the margins. Though the Living Newspapers tended to leave the solutions of the problems they introduced up to the audience, the pieces always had a clear agenda and were usually sympathetic to other New Deal legislation. In Seattle, the Federal Theatre Project mounted Living Newspapers that corresponded to hot political and social issues in the city from slums to public utilities to venereal disease prevention, which certainly helped to pack houses and may have helped to sway opinion, too.

Scene from the WPA Federal Theatre Project production "Clown Prince" in Seattle, 1937. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Librrary Special Collections, PH Coll 455.20.)

The Federal Theatre Project, like the Jameses, was also interested in the next generation of audiences. Glenn Hughes’s program at the University of Washington maintained a puppetry program from its early days and in the 1940s developed one of the finest educational programs in the nation for children’s theatre. In 1937, Flanagan sent her protégée Esther Porter to join the directorial team in Seattle, who oversaw a Children’s Theatre program during her brief stint in the Northwest. The Children’s Unit was the result of several influences. First, interest in children’s drama persisted in Seattle, in the Federal Theatre Project and in the Works Progress Administration (with whom the FTP were frequently in conflict) and it was thought that a Children’s Unit could improve the FTP’s relationship with the WPA. Secondly, after the departure of the Jameses, there was a desire to change the Federal Theatre Project’s public image, reducing the association of the federal theatre with radicalism. Finally, a Children’s Unit was a pragmatic solution to an economic problem: dwindling funds had forced the FTP to contract its operations, and the organization could no longer afford to keep touring the vaudevillians in its Variety Company. The Children’s Theatre mounted eight productions by May of 1939, six by the consolidated white performers and two by the Negro Unit. Though Porter’s own racial insensitivity brought her into conflict with the Negro Unit (particularly in her work with them on a production of Brer Rabbit and Tar Baby for the Children’s Theatre), making her role as the “caretaker” of the Negro Unit a difficult appointment, the Federal Theatre’s Children’s Theatre, to which she devoted her energies, established a lasting tradition for Children’s Theatre in Seattle, which continues to prosper today.

Scene from the WPA Federal Theatre Project production "See How They Run" in Seattle, 1938, University of Washington Professor George M. Savage's prize-winning play in the Federal Theatre Project new play competition. (Image courtesy of the University of Washington Librrary Special Collections.)

Finally, the Federal Theatre created opportunities for up-and-coming playwrights. Hallie Flanagan’s national new play competition invited playwrights who had never had a production on Broadway to submit scripts for consideration. The winner would receive $250 and a two-week run in New York. Though University of Washington professor George M. Savage, Jr., winner of the national search with his play See How They Run, never received the promised New York production, it was produced in both San Francisco and in Seattle, where the Federal Theatre Project’s final director, Edwin O’Connor, worked extensively with Savage to shape and hone the script.

Clearly, the Federal Theatre in Washington State did much more than relieve theatre artists on the dole: it made amateurs into troupes, it challenged racial barriers with mixed casts and crews, it engaged in locally relevant and important political conversations with the community, and it shared (with the University drama program) a growing interest in and commitment to creating a new generation of theatre-goers, ensuring that on the other side of the Depression, there would still be audiences.

Copyright (c) 2009, Sarah Guthu

For a longer history of the Federal Theatre Project and the Seattle unit in particular, see Barry B. Witham, The Federal Theatre Project: A Case Study (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).