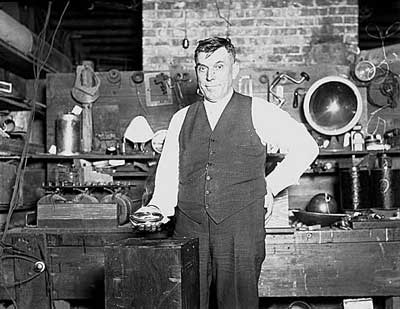

J.D. Ross, the superintendent of Seattle City Light, c. 1930. Ross's public utility battled for business with the privately owned Puget Power. Ross was fired by Mayor Frank E. Edwards in 1931, perhaps because Edwards feared he was gaining too much power. City voters overwhelmingly passed a measure in favor of public power, and Ross was reinstated. Click image to enlarge. (Courtesy Museum of History and Industry)The Living Newspaper One Third of a Nation presented a theatrical picture of the American housing crisis, and was used in Seattle to depict regional slums. (Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division.)

Power, a Living Newspaper, was one of the most significant productions mounted by the Seattle region of the Federal Theatre Project—a success due in large part to its timely application to civic conditions and concerns in the area.

The Living Newspaper opened in New York in March of 1937 and engaged a national debate over the nature of public or private utilities. Power focused on the efforts of the Tennessee Valley Authority, a fellow New Deal program struggling to establish a public power utility company that could provide lower-cost services to a wider demographic than leading privately owned utilities.

Working in broad strokes, Power cast private utilities and big capitalists as its villains. In scene after scene, local residents are cheated by padded rates, fail to qualify for service, or are offered electric power only if they can supply a large investment to entice the companies to expand into their area. In their own defense, the owners of private companies accuse the government of unethical business practices: they point to the government’s great wealth of resources and accuse federal programs like the TVA of attempting to undersell the private sector.

What was really under debate was the access to electric power and other utilities: Power asserts that all citizens have a right to such a service, while private business insists that access to electricity is a privilege that must be paid for. Though Power clearly took a stand on the matter of utilities, coming out strongly in favor of the government option, the play itself ended before a decision was reached, suggesting audiences continue the discussion outside the theatre, and reach a decision of their own.

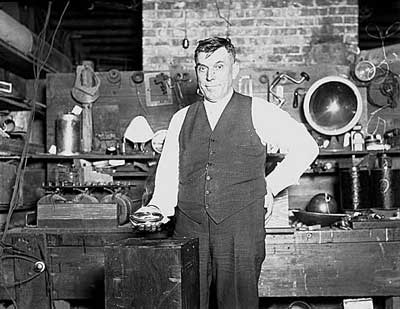

The link between the theatre and the city was particularly apt when Power opened in Seattle in July, 1937. At the time, the privately owned Puget Power and the public utility City Light were struggling for dominance as providers of electricity, a wasteful rivalry. City Light had some 2,100 miles of electric power lines in the city in 1937; Puget Power had 1500. In some places, lines for the two competitors ran down the same streets. Owing to this kind of duplication, more than 17,000 transformers were in place in Seattle, when a mere 9,000 would have sufficed to meet city needs. And though FTP director Hallie Flanagan insisted in 1936 that she would not have the Federal Theatre become a political mouthpiece, the choice of the Seattle FTP to seek sponsorship from City Light suggested a strong sympathy existed between the two public institutions.

The privately owned Puget Power plant, c. 1912. The FTP's Living Newspaper Power drew on regional politics to make a broader argument in favor of New Deal public utilities policies. Click image to enlarge. (Courtesy Museum of History and Industry)

The “sponsorship” relationship did not necessarily indicate a monetary exchange, however. Though some FTP sponsors did offset expenses of production, others helped advertise FTP productions, and some simply lent their names in public support of an FTP program. For Power, City Light lent props for the production and two spotlights for use outside the theatre at the opening. City Light also included advertising for the production in mailings to their customers. They allowed the Federal Theatre to hang advertising placards for Power on their lampposts, sent out special invitations to see the show, and helped to sell blocks of tickets. The other benefit to the Federal Theatre of engaging another public institution as a sponsor was that this allowed the FTP to apply their own box office credits toward production expenses, thus enabling them to develop a richer and more spectacular production.

The partnership was mutually beneficial. As a branch of the FTP, the Living Newspapers were committed to the New Deal and its fellow WPA projects, and Power was no exception to this rule. Its staunch support for publicly owned utilities cast a vote for City Light, a position reinforced by the dedication of an evening to their sponsor. No corresponding “Puget Power Night” was offered to counter “City Light Night,” an omission which local reviewers noted.

The sympathetic alignment of Power’s sentiments with City Light’s struggle for dominance may not have been subtle, but this doesn’t seem to have hampered the sponsor’s cause: five months later, in December, 1937, a City Light proposal to buy out Puget Power was receiving unanimous approval in local papers, though the final transfers of ownership to the former company would not occur until 1951.

Copyright (c) 2009 Sarah Guthu