Living Newspapers:

One-Third of the Nation<

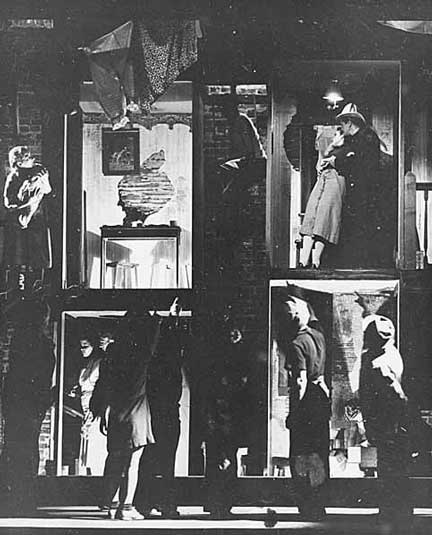

Scene from the Federal Theatre Project production of One Third of a Nation, Seattle, 1938. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division)

The longest-running production of the Seattle branch of the Federal Theatre Project was the Living Newspaper One-Third of a Nation. Drawing its title from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s second inaugural speech, in which he claimed that one of the great challenges to American democracy was the fact that one third of the nation remained "ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished,” the Living Newspaper presented the rise of slums in America (specifically New York), and campaigned hard for government housing projects.

One-Third of a Nation opens as a fire breaks out in a crumbling tenement in New York. The Voice of the Living Newspaper—more a character in One-Third of a Nation than merely a disembodied narrator—pairs with Angus Buttonkooper, the “Little Man” (and resident in a similar tenement) in search of an explanation of why affordable, clean, decent housing is so hard to come by. Together, the Voice and Angus track corruption in New York’s housing market, beginning with early grants by Trinity Church (and its maneuvers to evade exposure by early investigations into its profits) to families who would become some of the most prominent of American land magnates.

As the city expands, a landlord sits on his grass mat, which represents his property, and as the population increases, eventually desperate citizens fight to pay ever-increasing rents to squat on smaller and smaller portions of the landlord’s mat. The Little Man is shocked to learn that New York slums had been ravaged by cholera, though the Voice of the Living Newspaper reminds him that tuberculosis continues to decimate populations in the 1930s. The production suggests that slums breed crime, as desperate characters resort to petty theft in attempts to escape the dehumanizing misery of their circumstances.

One-Third of a Nation also tracks the process of the politicization of the Little Man. As the story progresses through more than a century of corruption, he becomes increasingly impatient and frustrated by the inequality of wealthy landlords and landowners and the condition of their hapless, impoverished, largely immigrant tenants. As the Living Newspaper moves closer to the present day, it begins to track the struggle to gain support for a program of government housing. The piece closes on the limited success of the Wagner-Steagall bill (whose funds were cut from a proposed 1 billion to 526 million before the bill passed), which could alleviate only 2% of New York’s slums. The Little Man and his wife resolve to continue haranguing the government until slums are removed and everyone in America can find a “decent” place to live; their rallying cry is a call to action, including their audiences in their urgent resolve.

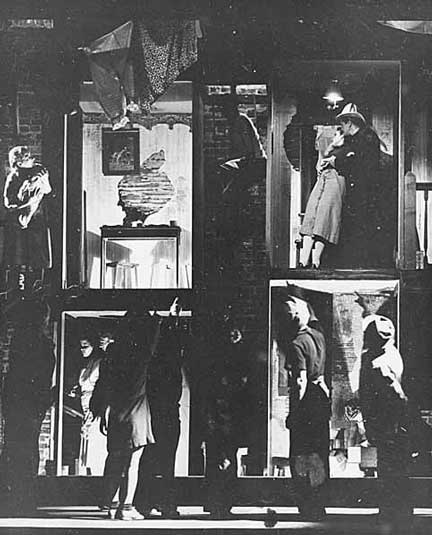

Federal Theatre Project works often engaged issues of class inequality, as does this scene from One Third of a Nation, Seattle, 1938. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division)

In Seattle, Guy Williams had planned to include One-Third of a Nation in an upcoming Federal Theatre Project season as early as July 1937, when the Project had enjoyed great success with another Living Newspaper production, Power. The next year, now under the aegis of Edwin O’Connor, One-Third of a Nation came to Seattle. As with Power, timing was crucial to the significance of the production and its participation in local politics. In 1938, the Seattle City Council was campaigning to create a Housing Authority that would allow the city to claim government funds for affordable housing, such as those earmarked in the Wagner-Steagall bill. However, the United States Housing Authority pointed out that Washington State lacked the enabling legislation that would allow it to establish a Housing Authority and apply for the long-term, low-interest loans offered by the government to replace slums.

An intricately staged scene from the Federal Theatre Project production of One Third of a Nation, Seattle, 1938. (Courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division)

As in other Seattle productions of national Living Newspaper projects, an effort was made to adapt One-Third of a Nation to local conditions, but the effort was abandoned. Esther Porter, who was working concurrently with the Negro Repertory Company on a production of Brer Rabbit for the Children’s Theatre, insinuated that her efforts to expose Seattle slumlords were thwarted when it became apparent that her investigations would lead the Federal Theatre Project into a critique of prominent Seattle citizens. However, the abandonment of a “localized” version of the play could just have easily been the result of budgetary and time constraints: the production was ultimately produced for a mere $242.75, and when the production’s slides arrived from New York, O’Connor realized that they were integral to the production, and that replacing them could harm the production. Furthermore, as the legislature was scheduled to reconvene in January, 1939, O’Connor had to move quickly to allow the Living Newspaper time to weigh in on the issue. However, the Seattle branch of the Federal Theatre Project did manage to incorporate at least half a dozen facts about Seattle’s own slums and tenements into the production, and the photographs Porter had begun to compile to replace the New York slides were displayed in the lobby during the production.

One-Third of a Nation opened on May 23, 1938. The Federal Theatre extended invitations to the the entire Housing commission, and though the initial response was good, audiences soon dwindled. O’Connor, who had hoped to run the production for a month, worried that the Federal Theatre’s consolidated theatre space in Rainier Valley was too far south of Seattle’s city center to entice audiences, and began a vital word-of-mouth advertising campaign for the production. O’Connor offered lectures and talks about the American housing problem, signs were placed in the backs of taxi cabs, blocks of tickets were sold to sympathetic organizations, and actors read scenes on the radio. The penniless campaign worked: the production ran until July 1938, and though its political message was blatant propaganda on the behalf of government programs, local reviewers seemed to forgive the production its faults. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, for example, claimed that the production was “overlong” and “admittedly exaggerated at times for effect,” yet at the same time insisted that it was overall “stimulating” and “thought-provoking,” and lauded the Federal Theatre for their multifaceted production, which utilized a wide variety of theatrical conventions and staging techniques. In 1939, the necessary enabling legislation was easily passed and resultant Seattle Housing Authority became one of the most active campaigns against slums in the United States.

Copyright (c) 2009, Sarah Guthu