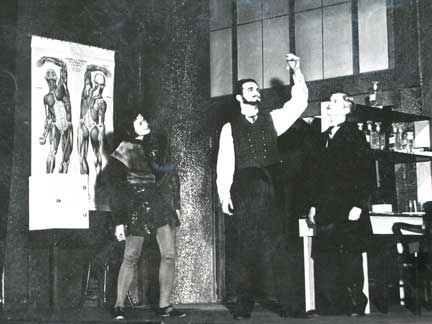

Scene from the Federal Theatre Project's production of Spirochete, in Seattle, 1939, which intervened in Seattle's public health debates around venereal disease. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 17.)The single most successful of all of the Seattle Federal Theatre Project productions was a Living Newspaper about a sexually transmitted disease. Spirochete presented the history of syphilis, from Europe’s initial contact with the disease (probably brought back by Columbus’s men from the New World) and its virulent spread, to the discovery of both the spirochete bacterium that caused the disease and the discovery and development of salvarsan, its first effective medical treatment, in 1908. The history lesson was framed by contemporary events in the United States: a raging debate about efforts to institute mandatory prenatal and premarital testing for the disease. For, though the discovery of salvarsan was almost 30 years old, syphilis continued to plague the American population, where a culture of shame and silence surrounded the disease and prevented the spread of accurate information. Many still assumed that the disease was a punishment for sin (a view represented by the character of the Reformer in Spirochete, who is angrily expulsed from the research laboratory), or that it was only contracted by the lower classes, “perverts,” or African Americans.

First staged in Chicago in April, 1938, as a part of WPA efforts to improve public health, Spirochete supported Surgeon General Thomas Parran’s December, 1936 declaration of a “war” on syphilis. As represented in the play, polite society’s avoidance of the topic was extreme—so much so, in fact, that the word “syphilis” did not even appear in print media until 1937. Perhaps surprisingly, the campaign for public health couldn’t always count on support from the medical establishment.

Government interest in establishing public health programs to increase awareness, monitor the spread of the disease, and treat the infected populace was seen not only as an attack on decency, but also as government infringement on private medicine. The situation was aggravated by class differences and the negative assumptions that surrounded the disease. While ordinary office visits cost patients about $3, for a syphilis treatment, a patient might be charged up to $25, and the cost of the Wasserman test to detect syphilis was unregulated. There were cheaper options: public clinics offered Wasserman tests at a predetermined (and usually) lower rates, along with salvarsan. However, patients who visited public clinics lost their anonymity, while those who could afford to pay for private diagnosis and treatment could be sure of doctor-patient confidentiality, an agreement which could understandably preserve a person’s reputation.

This facet of the war on syphilis (and the resistance it met) was not addressed in Spirochete; instead, the play presented medical researchers and doctors as valiantly struggling to preserve the human race from the horrors of the disease, and to protect them from overbearing moralists who would withhold a cure. Perhaps the Federal Theatre Project knew that, in order to be successful, government programs would need the support of the medical community.

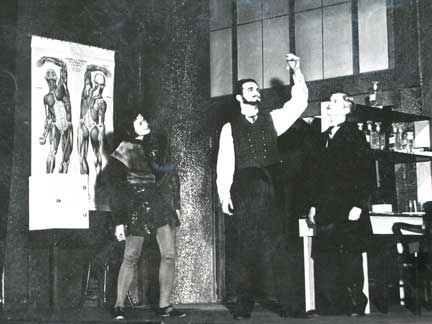

Scene from the Federal Theatre Project's production of Spirochete, in Seattle, 1939. This scene is probably from one of the two "legislation" scenes at the end of the piece. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 17.)

The situation in Seattle was similar to that in the rest of the nation. Though more than 50 people died of syphilis in Seattle annually in the 1930s, only 847 cases were reported in 1931, and only 1,232 were reported in 1939. As elsewhere, Seattleites assumed the disease plagued the lower classes, AfricanAmericans, and prostitutes. However, attitudes seemed to be changing by the end of the decade. In the fall of 1938, Bills 373 and 374 (requiring prenatal and premarital syphilis testing, respectively) began working through the Washington State Senate—and the Federal Theatre opened Spirochete in February 1939.

There were concerns about how to package the production. While the most pressing was to ensure that the play was not received as mere titillation, the FTP also didn’t want its production to be received as a dry lecture on the history of a venereal disease. The Seattle branch reached out to their local medical community as allies in a united fight against syphilis and engaged the Ladies Auxiliary of the King County Medical Society as their sponsor for the production. The Society supported the two Senate bills, though was concerned that too strong a show of support would alienate a public deeply uncomfortable with the thought of mandatory testing. The Society also reached out to doctors in the community, reassuring them that the government had no intention of eliminating parts of their practices.

Scene from the Federal Theatre Project's production of Spirochete, in Seattle, 1939. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division, UW Theatres Photograph Collection, (PH Collection #236), box 4, folder 17.)

A week before Spirochete opened, the Medical Society’s Bulletin mentioned the upcoming event. The Ladies Auxiliary reserved 150 tickets at a special 87-cent price, and on opening night, some 175 doctors filled a large block of the audience. The FTP distributed 35,000 handbills advertising the production, many through doctor’s offices and hospitals, and hung 3,500 posters. The Board of Health and the medical association bought air time before the opening, and ten 15-minute advertising spots were recorded, featuring scenes from the play. The play successfully united the FTP with the local Works Progress Administration, as well. Though the two New Deal programs suffered from a fraught relationship , exacerbated by a power hierarchy that was never clearly delineated, the FTP offered WPA employees discounted 10-cent ticket rates, who then comprised almost a third of Spirochete’s audience.

Scene from the Federal Theatre Project's production of Spirochete, in Seattle, 1939. This scene is probably from one of the two "legislation" scenes at the end of the piece. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division)

As the Bills had not yet been passed in the Washington Senate, the Seattle FTP altered Spirochete’s script to reflect the as-yet uncertain (however promising) status of the Bills in local politics. Instead of closing with a repentant legislator recanting his earlier attack on syphilis bills, the Seattle production closed as Bill 374 (requiring premarital testing) went up for the vote—a tactic that once again reminded audiences that the resolution of the issues presented in the theatre needed to be sought outside it. The Seattle unit also rewrote an earlier legislation scene so that legislators arguing against mandatory testing would not appear quite so sympathetic to the audience.

Spirochete was the biggest hit the Seattle FTP ever had. Almost 3,000 people attended the productions, nearly 1,000 more than attended any other Seattle FTP production at the Metropolitan theatre), and the show grossed just over $1,000, which was $400 more than the Seattle FTP made on any other production. Surprisingly, the members of the Ladies Auxiliary gave the show only a tepid mixed review, describing Spirochete’s script as repetitive and uninteresting, the production as amateur and the music as ear-splitting in the Medical Society’s Bulletin and casually noting that other members seemed to enjoy the production more. And though the Post-Intelligencer claimed that the production was a “historical lecture” rather than “entertainment in the usual sense,” the paper did note the production’s accuracy and meticulous attention to detail. And though the Post-Intelligencer claimed that the premarital testing mentioned in the play was an embarrassing suggestion, the paper didn’t shy away from printing the word “syphilis,” nor from naming prominent members of society and community leaders who were in attendance. Bills 373 and 374 passed into law the next month—March 1939—and were scheduled to go into effect January 2, 1940. The Seattle FTP, invigorated by the success of Spirochete, would begin developing a new Living Newspaper, Timber, about the local forestry industry—a project that unfortunately would be cut short when the FTP program was ended.

Copyright (c) 2009 Sarah Guthu