By Franklin Faust and Genevieve Wanucha

If you ask a group of Seattle King County locals over the age of 65, you can bet that several of them will have heard about the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study—they might even be enrolled as research participants or know a friend who is. That’s because this study, launched at the early ADRC in 1986, has followed the physical and cognitive health of 5,750 members of major health maintenance organizations in Seattle for decades. At any given time, over 2,000 people are participating, with almost perfect rates of follow up for the check-ins that take place every 2 years. Of inherent interest to many aging individuals, ACT focuses on finding ways to delay or prevent dementia and declines in memory and thinking. It aims to deepen understanding of how the body, especially the brain, ages—and discover how people can age in the healthiest possible ways.

A Living Laboratory for Brain Aging

The ACT study functions as a population-based “living laboratory” for brain aging research. Researchers select participants at random from a pool of Seattleites who have reached age 65 and are in relatively good health, and then follow their cognitive trajectories until death. If a participant ever develops dementia, researchers can rewind that individual’s history and look for clues as to what lifestyle, medical conditions, or local environmental factors may have contributed to their cognitive decline. There are also secrets to learn from "super-agers" whose minds show cognitive resilience to aging and disease and preserve their mental function remarkably well into old age. ACT’s goal is to search for patterns in an aging population that point to lifestyle factors that act as risky pitfalls or supportive bridges on the journey towards lifelong brain health.

Paul Crane, MD, MPH and Eric Larson, MD, MPH at the 2019 ACT Symposium

“ACT is the world's only study that can link outcomes for dementia, frailty, and aging to data that captures each participant's whole health history, including medical, laboratory, and pharmacy records," says co-principal investigator of the ACT Study, Paul Crane, MD, MPH, UW Professor of General Internal Medicine. “If you're really interested in the form of dementia that's in the community, the ACT study is the place to go,” adds Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, now ADRC Associate Director and Senior Investigator and recent past Executive Director at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute where he leads ACT.

The origins of ACT can be traced back to Larson’s guiding motivations. As co-founder of the Geriatric Family Services Clinic in 1978, the first clinic on the West coast to provide impaired older persons with comprehensive evaluation for Alzheimer’s disease, he already had decades of experience following the trajectory of people developing dementia by the time the ADRC began to form. The geriatrics clinic, along with outpatient clinics at the VA and Harborview Medical Center, became the primary source of research subjects in the ADRC’s budding longitudinal study. A groundbreaking feature of an Alzheimer’s study at the time, participants also gave consent to ultimately donate their brains for autopsy, enabling the ADRC to connect an individual’s meticulously documented clinical history with neuropathological findings from their brain tissue.

However, Larson had always wanted to answer the question: “What can we learn from our research that will ultimately allow people to reduce age-associated cognitive decline and, ideally, prevent and delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease?”. He knew that would mean reaching beyond a targeted cohort model, in which a volunteer’s interest in participating was often based in already present symptoms or having a family history of dementia. “The vision of the ACT study was driven by the fact that in the early days of my work with Alzheimer's, there were a lot of findings that made a splash and then disappeared. They couldn't be reproduced because they focused on small populations and not on a community sample,” said Larson. He was eager to create a study well suited for answering questions about dementia prevention in the general community. It would combine attributes of an observational population study and ADRC expertise in neuropathology and genetics.

The dream became a reality in 1986, when Larson and ADRC’s Walter Kukull, PhD were awarded an NIA grant to start an epidemiological model of an Alzheimer’s incident case registry, similar to cancer registries which have been used extensively to better understand cancers. They established the Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Registry from a pool of 25,000 individuals aged 60 and older who were members of Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Health Research Institute. From this early registry, Larson and Kukull recognized that a true cohort study would be best to study Alzheimer’s disease, akin to the cohort studies like the famous Framingham Heart Study and Honolulu Heart Watch. They then recruited a randomly selected community sample, formally named the Adult Changes in Thought study in 1994.

Today, the ACT study maintains extensive data resources in collaboration with the ADRC, including an unrivaled population of people over 90 years old and a collection of over 850 brains—one of the largest in the world. The ACT team attributes the size and the richness of the data to the comprehensiveness of care provided in Group Health, now Kaiser Permanente Washington, and years of detailed medical records that are now stored electronically. The ACT study has learned many lessons to date, which has contributed data to 98 funded grants, with results published in over 350 scientific articles on brain health and dementia risk.

A Growing Strength in Neuropathology

Courtesy, Ann McKee Lab

ACT is the only truly population-based study involving autopsy and the study of disease in the brain, or neuropathology–a unique feature that shows how ACT and the ADRC complement each other’s strengths. “We truly intersect and interact synergistically at the level of the neuropathology program,” says Thomas Grabowski, MD, ADRC Director. It was Thomas Montine, MD, PhD, Director of the ADRC from 2012-2016, who did the heavy lifting of uniting ACT and the ADRC through common work in neuropathology, allowing ADRC expertise to make even more scientific use of each ACT participant’s brain. “The way the ADRC Precision Neuropathology Core’s workup looks these days bears Tom Montine’s stamp,” says Grabowski.

When Montine accepted a new position at Stanford University, he turned over leadership of the core to C. Dirk Keene, MD, PhD, who has since launched a powerful collaboration with the Allen Institute for Brain Science to adapt tissue dissection and preservation protocols to next-generation technologies that can identify and measure pathology in autopsy tissue and analyze the patterns of gene expression in single neurons. Under Keene’s lead, the Precision Neuropathology Core uses identical, state-of-the art methods to analyze the donated brains of both ACT study and ADRC participants. This data resource has given researchers the ability to investigate the biology of common forms of late-onset dementia and make conclusions that generalize to the local aging community.

In a seminal ACT-ADRC contribution, UW Pathology’s Joshua Sonnen, MD, now a neuropathologist at McGill University, along with Montine, Larson, and others, evaluated brain autopsies from ACT and other large population studies. Publishing the paper 'Ecology of the Aging Human Brain' in 2012, the team became the first to report a high prevalence of multiple different pathologies in the brains of cognitively normal older people and characterize it as a late, complex pathology in the community population.

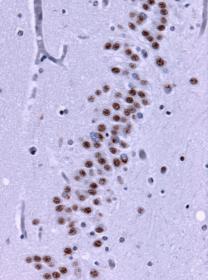

Under the microscope, brain tissue from a person with frontotemporal lobe degenerations shows deposits of TDP-43 (brown). Wikimedia Commons.

Caitlin Latimer, MD, PhD, co-Lead of the ADRC Precision Neuropathology Core, added to this story in 2019, producing strong evidence for a little recognized factor behind the resilience or resistance to Alzheimer’s pathology seen in some of ACT’s oldest participants. Her most striking finding was that almost all of the brains from older people with symptoms of dementia showed buildup of a protein called TDP-43, yet the brains of age-matched people who were resilient or resistant did not. The field is now considering whether a secret to resilience to Alzheimer’s disease in late life simply depends on never developing TDP-43 pathology. Researchers hope that this ecology of brain disease proteins in the aging brain will inform future biomarker studies and clinical trials with older individuals – setting the stage for new insights into the factors of risk and resilience that influence the susceptibility to common forms of dementia.

Since the complexity of the aging human brain became apparent, ACT and the ADRC have worked closer together to understand the common forms of dementia affecting the community. More powerful together than as separate institutions, the two projects paint a detailed picture of each individual who takes part in research, connecting the dots between cellular processes and lifestyle factors to arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of brain health and disease. “I don't think there's anything in the world that matches the richness of our data and the way we can go back so far,” says Larson. The emergence of this unique strength at the ADRC, and new ADRC/ACT collaborations with the Allen Brain Institute, is fulfilling ADRC Founding Director George Martin’s early dreams of genetics and epidemiology coming together to benefit Alzheimer’s research. •