People sign up for our mailing list and learn about our resources and clinical trials at Discovery Conference 2018. Photo credit: Kailee Powers, Alzheimer's Association, WA Chapter

We bring you some highlights from the 33rd Discovery Conference of the Alzheimer's Association Washington State Chapter, with links to related information.

Hopeful Aging

Some of the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center team with Bob LeRoy of the Alzheimer's Association and John Zeisel of Hearthstone Alzheimer Care. (3rd from left)

The 2018 Discovery Conference, ‘Enhancing Community Wellbeing,' began, at least thematically, even before the actual April 27th event. At a pre-conference lecture held at the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center the night before, Discovery keynote speaker John Zeisel, PhD, CEO and President of Hearthstone Alzheimer Care in Massachusetts and President of the I'm Still Here Foundation, shared his mission to change the public narrative about dementia to hope, rather than despair. It's been hard to do this, he said, because the of persisting stigma and fear surrounding dementia.

Stigma comes about when people think about dementia only in terms of the very last stages of the disease, leading to the sense that 'nothing can be done'. Yet, Zeisel knows from his work that people with dementia retain a sense of self and personal narrative. Helping to engage a person's self through enjoyable activities can improve symptoms often thought of as intractable medical issues, such as anxiety, apathy, and distress. But, seeing this possibility requires adopting the perspective of hope that something can be done to improve the experience of dementia and lessen the burden of caregiving.

According to Ziesel, there are three kinds of hope: wish; spiritual faith; and another kind of hope powered by a belief that one can make a difference and support the human rights of to dignity and respect for people with dementia.

Confronting dementia caregiving with hope, instead of despair, can have profound consequences. "Because dementia can present ambiguous situations, a sense of despair that nothing can be done leads to fear, anger, quick fixes, and guilt on the part of family members," said Zeisel. "In contrast, a hopeful outlook generates curiosity about ways to handle the tricky situation, which become part of a 'slow campaign'." Examples include communicating with the person in ways that avoid demanding a person to use short term memory, using name tags at social events, making sure that regular outings or errands occur on the same time every week, and taking advantage of retained procedural memories for hobbies and and activities such as knitting, painting, walking, drumming, ect.

Zeisel's recipe for cultivating the "grit" needed for this caregiving journey hinges on asking for help and support without feeling shame and guilt, in order to take care of one's self and health: exercise, a good diet, adequate sleep, managing stress through meditation, and "not sweating the small stuff." And, the most essential ingredient, hope.

Symptom Insights and Interventions

Emily Trittschuh, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at UW Medicine, demystified the "Three D's": delirium, depression, and dementia for geriatric specialists and primary care providers who are on the front lines of recognizing and addressing these symptoms in their aging patient population. These syndromes, which can overlap in patients, can have serious consequences if left untreated or misdiagnosed. Trittschuh shared case studies and clinically informative statistics to untangle these three syndromes. In a study of 459 hospitalized patients over the age of 70, 8.5% of the patients percent showed delirium and 26.3% showed depression, and the syndromes overlapped in 5%. Those with syndrome overlap had higher odds of functional decline over one month and nursing home placement after one year. Also important information for clinicians, patients with delirium often have a history of depression, while depression is known to follow delirium.

Tatiana Sadak, associate professor of psychosocial and community health at the UW School of Nursing and ADRC affiliate member, focused on practical ways to manage stress and distress behaviors in people living with dementia. She recommends identifying the cause of the distress and tailoring the intervention to address the unmet psychological or physical need, environmental irritant, or psychiatric issue. Sometimes, a situation demands a care partner adjust their approach, for example by exercising “unconditional positive regard,” which means reassuring, validating and comforting, instead of confronting, challenging, or explaining when a loved one with dementia makes a mistake because of memory loss. In the case of an environmental irritant, she recommends changing the scene, such as eliminating the clutter or noise or moving to a calmer space. For more serious behavior issues, such as depression, anxiety, or agitation, Sadak turns to evidence-based interventions. Here are some ideas, and the evidence backing them up. (Of course, evidence-based interventions require a full understanding of the protocols.)

- Physical exercise of any kind or intensity or wheelchair biking

- Individualized music

- Simple Pleasures, a multi-level sensorimotor intervention that enhances opportunities for self-initiated activities and social interaction, funded by New York State Department of Health

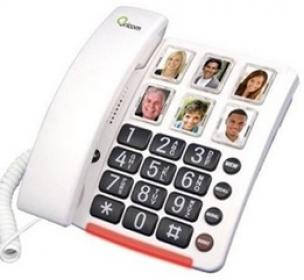

A similar theme appeared in the workshop on frontotemporal degeneration (FTD), a non-Alzheimer's disease cause of early-onset dementia, led by the Kimiko Domoto-Reilly, assistant professor of neurology at UW Medicine. She gave an overview of how the specific pattern of brain cell death determines whether FTD impacts language comprehension, speech and/or behavior or motor function. Drawing on her experience treating people in the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center, Domoto-Reilly emphasized that intervention strategies should be tailored to the person's specific challenges, especially for people struggling to find words, speak, or understand speech. To aid communication, asking multiple choice questions or presenting a choice between two options can help a person with FTD indicate their preference with minimal frustration. For example, don't ask "What do you want for dinner?" but rather "Would you like spaghetti or salmon for dinner?" In early stages of FTD, people may lose the words for specific objects. Domoto-Reilly noted that using gestures or image aids to communicate taps into retained strengths of visual perception and long term memory.

Gizmos and Gadgets to the Rescue

It's hard for anyone to imagine life without our handheld computers, cell phone location apps, web-based calendars, and smart TVs. Can personal technology similarly become a cornerstone for people living with memory loss or dementia? Maureen Schmitter-Edgecombe, professor of psychology at Washington State University would have you imagine a house with motion sensors in the rooms that monitor the resident’s activities. A computer program then uses that information to remind the resident to do critical tasks such as turn off the stove burner or faucet, lock the door at night, take medications at specific times, or to notify a care partner if something seems abnormal, such as the person staying in one spot for an extended period.

Schmitter-Edgecombe offered examples of interventions and smart environment technologies to help persons with dementia compensate in their daily lives for declining memory. Find links for the informational videos and materials about several different groups of aging assistive technologies, on the WSU Aging Assistive Technology website.

Going forward, her team in the Aging and Dementia Neuropsychology Laboratory wants to better interpret the dynamic information about the home sensors provide, to model the expected activity patterns and where people with memory loss are likely to have the most trouble. (She also happens to have mentored Carolyn Parsey, assistant professor of neurology at UW Medicine, a new neuropsychologist at the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center!)

Creating Dementia-Friendly Programs

A perennial invigorating presence at the Discovery Conference, members of the grassroots movement Momentia held workshops on the theme of empowering people with memory loss and their loved ones to remain active and connected in the community. One of the guiding principles of Momentia is that persons living with memory loss are the experts on their own experience and deserve to have their ideas and perspectives recognized. The Discovery workshop put this principal into action with a live demonstration of a community forum on creating dementia-friendly programs, such as walking groups, food bank volunteering, and art gallery discussions. Sitting around a table, people living with memory loss each chose an object on the table that sparked joy, energizing them to brainstorm, and then vote, on program ideas ranging from music concert series to petting zoos.

A community forum on creating dementia-friendly community, for and by people living with memory loss

“It felt useful to demonstrate how photos and tangible objects can be a way for people with dementia to communicate their program ideas," said Marigrace Becker, program manager of community education and impact at the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center, who co-led this workshop along with Keri Pollock, Ruth Egger, and Daphne Jones." People know what they love about their community, they know what they enjoy doing – this model insures everyone has a voice at the table.” This community forum approach was used in the Our Time Has Come workshop offered by the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center.

“Last year, it felt like we were planting seeds," said Becker. "This time around, people came up afterward and shared the programs they were working on already – Alzheimer’s Cafes and more. It’s exciting to see all the progress that’s been made across the state in one short year!”

- View the Momentia Seattle Calendar

- View the Community Events & Programs at the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Debby Tsuang, professor of psychiatry & behavioral sciences at UW Medicine and co-investigator in the UW ADRC, has studied Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) for 25 years, and gave a thorough overview on the disease and current research directions. The 2nd most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's, DLB affects 1.4 million Americans. The condition is underdiagnosed because the symptoms of DLB overlap with those of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and psychiatric disorders, so the field is focused on finding biological markers to improve the specificity of diagnosis of people during life and pave the way for effective clinical trials.

- ADRC’s Debby Tsuang Joins a New Multi-Center Consortium For Studying Lewy Body Dementia Biomarkers

- Recently, the UW Memory and Brain Wellness Center became a new Research Center of Excellence for Lewy Body Dementia

Tsuang said that early diagnosis of DLB has many benefits, such as prevention of the use of medications that increase the risk of psychosis in patients with DLB; time for families to plan medical and legal affairs; and time to build a support system to stay independent and maximize quality of life. She highlighted alternative therapies for DLB, including Tai Chi to improve gait and balance, and remembrance therapy, music therapy, and pet therapy to enhance wellbeing and mood.

Discovery Conference 2018 included many more workshops on topics such as improving dementia care in rural areas to the impacts of federal Alzheimer's disease research funding- Stay tuned for stories on these topics. Thank you to Elisabeth Lindley, registered nurse practitioner at the UW MBWC clinic, who worked on the 2018 Planning Council to provide input on the speakers and topics for this year's Discovery Conference.